Most people drink coffee to wake up. But the cup you’re holding right now may be doing something far more important: protecting your brain from diseases that often show up decades later.

Decades of research now point to something specific. Your daily coffee habit — depending on how much you drink and how consistently you drink it — appears to be one of the more accessible things you can do to keep your memory sharp as you age.

We’re not talking about a vague “might be good for you” claim. We’re talking about large-scale studies, brain scans, and data from hundreds of thousands of people. The evidence is specific, and it points to a clear sweet spot.

The “Goldilocks Zone” for Brain Health

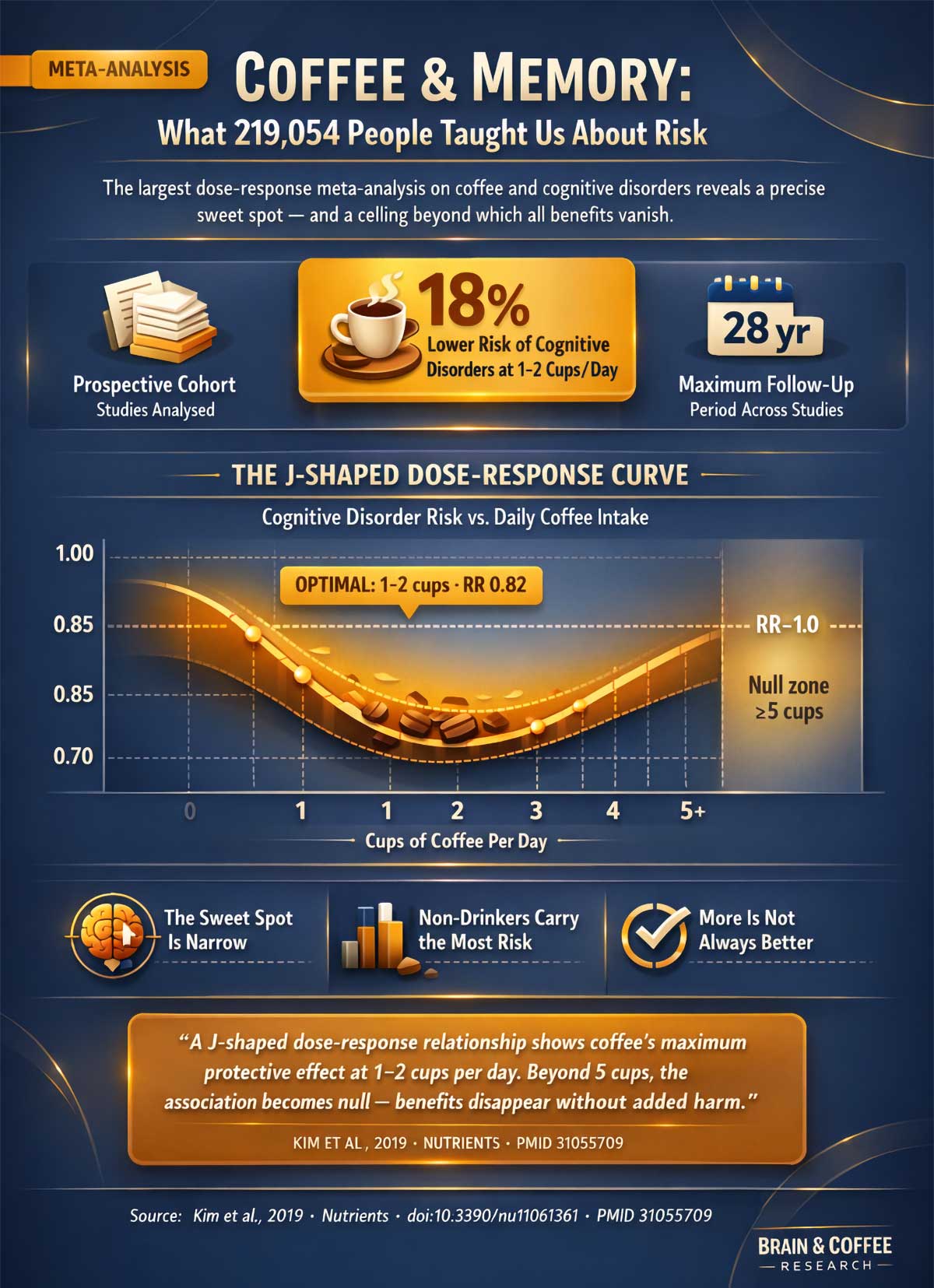

Not all coffee habits are equal when it comes to memory protection. A major 2019 meta-analysis published by Kim et al. pulled together 29 prospective cohort studies covering 219,054 participants. That’s a huge pool of data. Researchers tracked coffee intake against the development of cognitive disorders — including dementia and Alzheimer’s disease — over follow-up periods ranging from 4 to 28 years.

These 29 studies don’t stand alone. They build on a foundation of earlier research pointing the same direction. A 2013 meta-analysis by Arab et al., covering 34,282 participants across nine cohorts, also found an inverse relationship between coffee intake and risk of cognitive decline, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. That two large independent meta-analyses — one from 2013, one from 2019 — reached similar conclusions strengthens the case considerably. The following sections focus on six key studies that best illustrate the specific mechanisms and findings, but they sit within this broader, converging body of evidence.

What they found was a non-linear, J-shaped curve. That means the relationship between coffee and brain protection isn’t simply “more is better.” There’s a peak — and then the benefits drop off.

That peak sits at roughly 1–2 cups per day. At that level, drinkers had an approximately 18% lower relative risk (RR 0.82) of developing cognitive disorders compared to non-drinkers. It’s a meaningful reduction, and it comes from a modest, manageable habit.

What happens past that peak? The curve flattens out. At five or more cups per day, the protective association essentially disappears. That’s what researchers call a “null association” — you lose the benefit without gaining anything. Coffee past that point becomes just a caffeine habit with no added brain protection.

Think of it like watering a plant. The right amount helps it grow. Too little and it wilts. Too much and you drown the roots. Coffee’s effect on memory works in a similar way.

One practical note: in most research studies, one “cup” means roughly 8 oz of brewed coffee, containing about 95–100 mg of caffeine. So “1–2 cups” in this context means 95–200 mg of caffeine total. A standard 12-oz Starbucks “tall” would count as roughly 1.5 research cups, and a large 20-oz drink would push well past the two-cup mark. Knowing this helps you translate study recommendations to what you’re actually drinking.

What Coffee Does to Your Brain in the Short Term

The long-term benefits are impressive, but coffee also changes how your brain works right now — specifically in the brain areas tied to memory and focus.

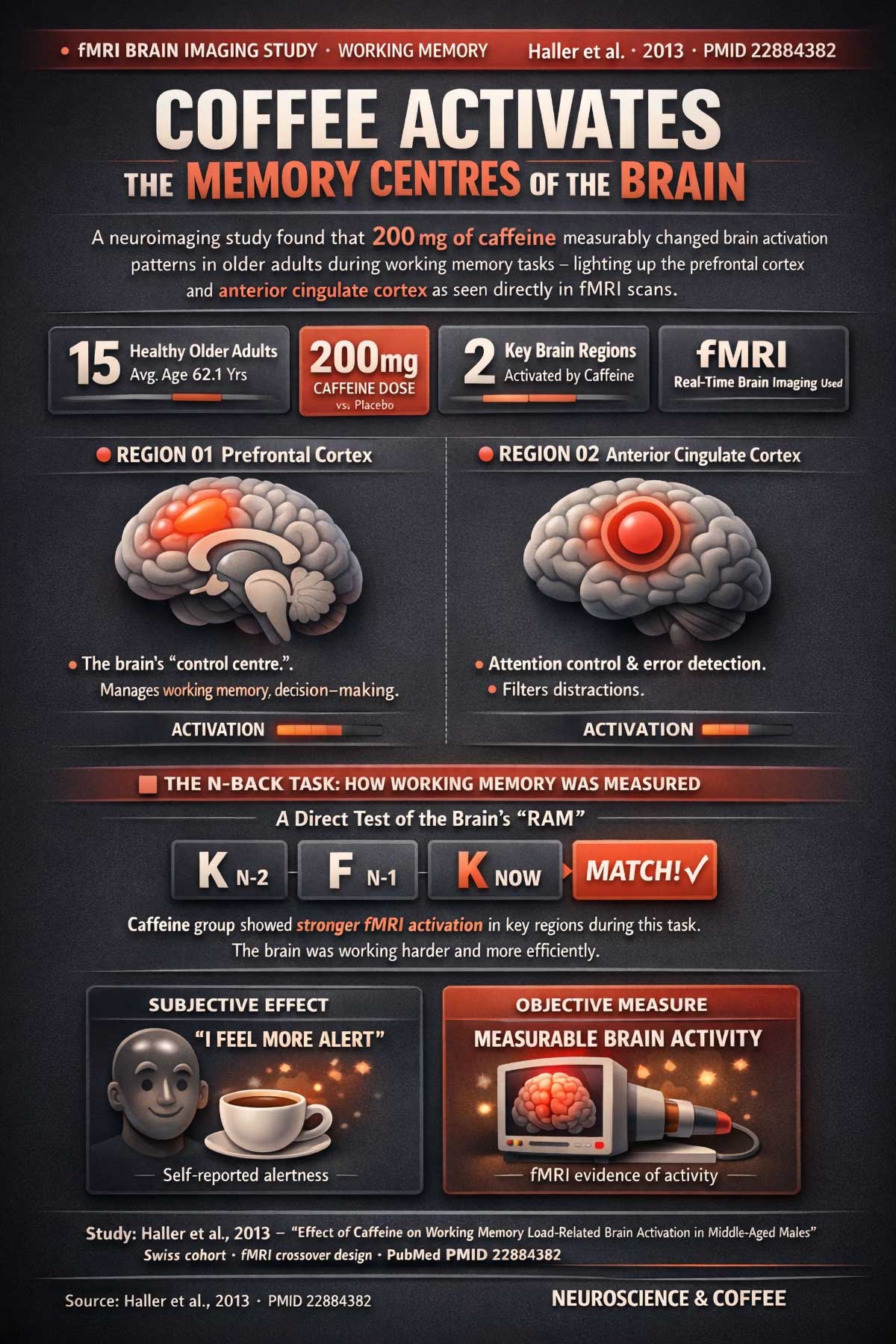

A 2013 study by Haller et al. gave healthy older adults (average age 62) either 200 mg of caffeine or a placebo, then put them in an fMRI scanner while they performed a demanding memory task called the n-back test. This task requires holding information in your mind and updating it constantly — it’s a direct measure of working memory.

The results were telling. The caffeine group showed stronger activation in two key brain regions: the prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex. These areas are involved in decision-making, attention control, and holding information in mind. In simple terms, caffeine lit up the parts of your brain that matter most for focused, precise thinking.

There’s an important distinction here. “Feeling alert” is not the same as performing better on memory tasks. Caffeine doesn’t just make you feel less tired — it changes how your brain processes and holds information. That’s a meaningful difference. One is a subjective sensation. The other shows up in measurable brain activity.

Pattern Separation: The Memory Skill You Didn’t Know Existed

Working memory is one thing. But what about forming strong, lasting memories in the first place? This is where coffee research gets genuinely interesting.

A 2014 study by Borota et al. tested 160 healthy young adults (ages 18–30) on a type of memory called pattern separation. This is the brain’s ability to tell apart two very similar things — like remembering whether you parked on Level 3A or 3B, or distinguishing between two nearly identical faces. It’s a precise and often overlooked memory function that tends to decline with age.

Here’s the key detail: participants were shown a series of images and then given either 200 mg of caffeine or a placebo — but the dose came after the learning session, not before. Researchers wanted to isolate whether caffeine helped with memory consolidation (the process of locking memories in) rather than just initial attention.

Twenty-four hours later, they were tested again. The test included similar “lure” items — images that closely resembled but weren’t identical to those they’d studied. The caffeine group was significantly better at correctly identifying these similar lure items as different from the originals (p < 0.05). That’s the gold-standard measure of pattern separation: not just recognizing something you’ve seen before, but catching the subtle difference between two things that look nearly the same.

The takeaway is worth sitting with. Caffeine didn’t help because it made people more alert during learning. It helped because it strengthened what the brain did with the information after the learning was over. That post-encoding window — the hours after you take something in — appears to be a real opportunity for caffeine to do meaningful work.

The Long Game: Protecting Against Alzheimer’s and Dementia

Short-term brain performance matters. But the bigger question for most people is this: can coffee protect your brain decades from now?

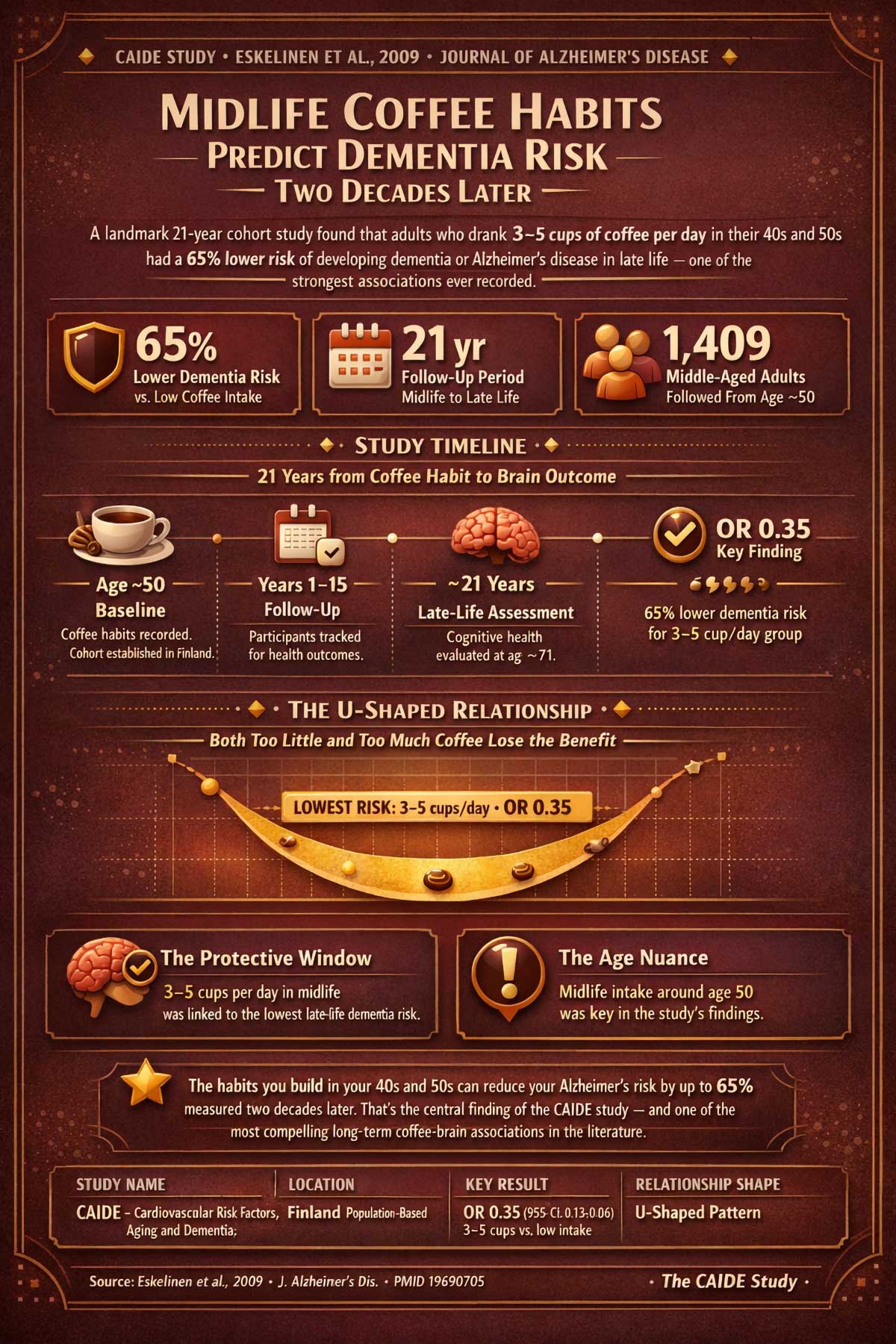

The CAIDE study, conducted by Eskelinen et al. (2009), followed 1,409 middle-aged Finnish adults for approximately 21 years. Participants were around 50 years old at the start. Researchers tracked their coffee habits in midlife and then assessed their cognitive health in late life, looking specifically at dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

The results were striking. People who drank 3–5 cups per day in midlife showed a 65% lower risk of developing dementia or Alzheimer’s in late life compared to those who drank little or no coffee (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.13–0.96). The relationship followed a U-shape, meaning that both very low and very high intake lost the protective edge.

This study matters because it addresses the timeline question directly. The habits you build in your 40s and 50s appear to have measurable consequences for brain health in your 70s and beyond. That’s not a correlation you can afford to dismiss.

It’s worth addressing something directly: the CAIDE finding of 3–5 cups looks different from the Kim meta-analysis finding of 1–2 cups as the sweet spot. Both are accurate — they’re measuring different things in different populations. The CAIDE study followed middle-aged adults specifically, and the outcome was late-life dementia measured two decades later. The Kim meta-analysis pooled studies across different age groups and a wide range of follow-up periods, which shifts the average optimal dose downward. What this likely means is that the ideal amount may depend on where you are in life. For most adults seeking general cognitive protection, 1–2 cups appears to be the safest, most broadly supported target. For adults in their 40s and 50s who are specifically focused on long-term dementia prevention, the midlife data suggests that 3–5 cups may offer additional benefit — though that should always be weighed against individual caffeine tolerance and other health factors.

Why might this happen? Part of the answer lies in how coffee interacts with two major forces that damage brain tissue over time.

Oxidative stress is the slow, cellular-level damage caused by unstable molecules called free radicals. Coffee is rich in polyphenols — plant compounds with antioxidant properties that neutralize these molecules. Chronic inflammation is another contributor to Alzheimer’s disease, and coffee’s bioactive compounds appear to reduce inflammatory markers in brain tissue.

The combination of antioxidant activity and anti-inflammatory effects may be why habitual coffee drinkers, across many studies, show better outcomes on measures of brain aging.

Why Consistency Matters More Than You Think

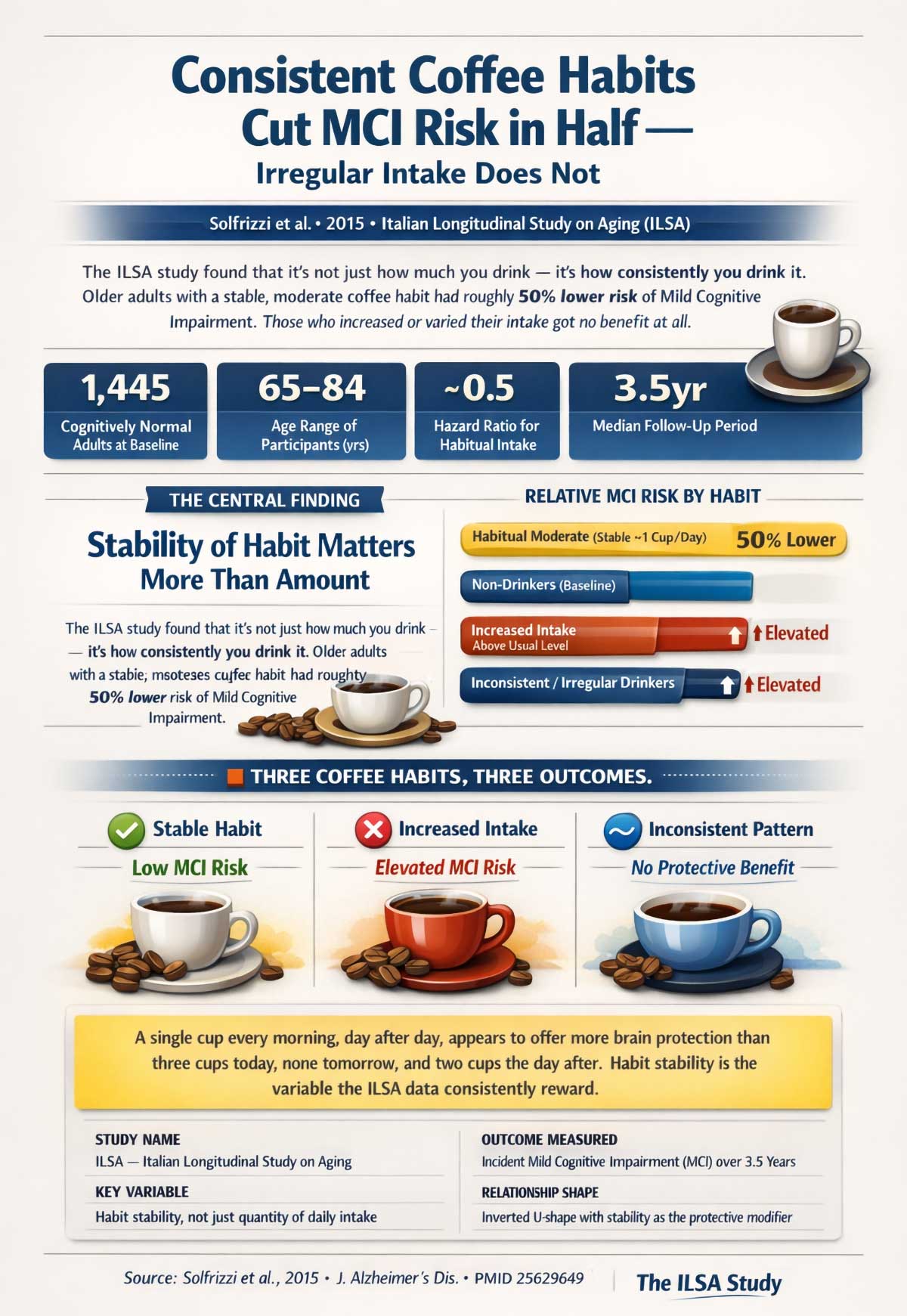

One of the most overlooked findings in coffee-and-brain research is about habit stability. It’s not just how much you drink — it’s how reliably you drink it.

The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging (ILSA), analyzed by Solfrizzi et al. (2015), followed 1,445 cognitively normal older adults between ages 65 and 84 for a median of 3.5 years. The study tracked coffee intake patterns and measured who developed Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) — a condition often considered an early warning sign for dementia.

The findings were nuanced and important. The key variable wasn’t just how much coffee people drank — it was whether their intake was stable over time. People who maintained consistent, moderate consumption of about one cup per day had roughly half the risk of developing MCI compared to those whose habits were inconsistent (HR ~0.5). Crucially, the elevated risk wasn’t only among non-drinkers. People who increased their intake above their usual level also showed higher MCI rates. The protective signal came specifically from habitual, steady consumption — not from any particular amount on any given day.

This runs counter to the assumption that more coffee automatically means better protection. What the data suggest is that your brain adapts to a stable caffeine routine. When that routine changes — even by adding more coffee — the adaptation is disrupted. The neuroprotective benefit appears to depend on steady, predictable intake rather than reactive or irregular consumption.

If your coffee habit is all over the place — three cups on Monday, none on Tuesday, four on Wednesday — you may be getting far less brain protection than someone who quietly drinks one cup every single morning without much thought.

How Coffee Actually Shields Your Brain: The Mechanism

Understanding why coffee is protective helps make sense of the patterns researchers keep finding. Two main pathways stand out.

The adenosine receptor story is central to how caffeine works. Adenosine is a chemical that builds up in your brain throughout the day. Its job is to make you feel tired — it docks onto receptors and signals that it’s time to slow down. Caffeine is structurally similar to adenosine, so it slips into those same receptor slots without triggering the slowdown signal. The result is reduced mental fatigue and better signal transmission between brain cells.

But there’s more to coffee than caffeine. Two other compounds deserve mention: trigonelline and chlorogenic acid. Trigonelline is a compound that research suggests may have neuroprotective properties, including potential effects on nerve cell survival. Chlorogenic acid is a potent polyphenol linked to reduced brain inflammation and lower blood-brain barrier permeability to harmful substances.

These compounds work alongside caffeine rather than instead of it. Decaf coffee retains most of the polyphenols, which means it still offers some antioxidant and anti-inflammatory value. But it loses the adenosine-blocking action — the mechanism most directly linked to working memory performance and the short-term cognitive effects seen in studies. For people who can’t tolerate caffeine due to sensitivity, anxiety, or heart conditions, decaf is a partial option. It likely offers some long-term neuroprotective benefit through polyphenols, but it probably won’t replicate the full range of effects seen in caffeinated coffee research.

Brewing method also plays a role. Filtered coffee, espresso, French press, and instant coffee all extract different amounts of caffeine and polyphenols. Filtered drip coffee is the preparation most commonly used in large epidemiological studies, so the dose recommendations above are best matched to that method. Espresso contains more caffeine per ounce but is typically consumed in smaller volumes. If you drink mostly espresso or other concentrated forms, account for that when estimating your daily caffeine intake.

A note on individual response: The research described here reflects population-level patterns. Individual responses to caffeine vary considerably based on genetics — specifically variants in the CYP1A2 gene, which controls how quickly your liver breaks caffeine down. Fast metabolizers clear caffeine quickly and may need slightly more for the same effect. Slow metabolizers may feel the effects of caffeine for hours longer, making the same dose feel much stronger. Tolerance, medication interactions, and underlying health conditions also affect how caffeine behaves in your body. The population-level sweet spot is a useful guide, but your own ideal intake may differ.

A Practical Memory-Boosting Coffee Protocol

Based on what the research shows, here’s a clear, evidence-based framework for getting the most out of your coffee habit.

The right amount — and who it applies to: For most adults, 1–2 standard cups per day (roughly 95–200 mg of caffeine) is the most broadly supported target for general cognitive protection. If you’re specifically in midlife — your 40s or 50s — and focused on long-term dementia prevention, the CAIDE data suggest 3–5 cups may offer stronger protection, though always within your personal tolerance. Keep in mind that one research “cup” is 8 oz of brewed coffee; adjust if you’re drinking large-format drinks or concentrated espresso.

The timing question: The Borota et al. findings suggest that consuming caffeine after a learning session may be especially effective for locking in what you just learned. If you’re studying, reading something important, or in a training session, a coffee afterward — rather than before — may strengthen retention.

Keep it consistent: The ILSA data are clear on this point. A stable daily habit outperforms an irregular one. Your brain appears to adapt to a predictable caffeine routine. Fluctuating intake — even upward — may eliminate the protective effect entirely. Pick an amount that works for your body and stick to it.

Know your ceiling: The Kim et al. meta-analysis found that five or more cups per day is where the protective association fades. There’s no evidence that drinking more gives you more protection. That’s the point where the curve flattens to zero benefit.

Don’t ignore the basics: Coffee works best alongside quality sleep, regular movement, and a diet rich in whole foods. These aren’t optional extras — they’re the foundation on which any brain-health habit rests.

Conclusion

For decades, coffee was treated as a guilty pleasure — something to tolerate despite its downsides. The growing body of research tells a different story.

At the right dose, consumed consistently, coffee appears to do things that genuinely matter for your brain. It sharpens working memory in the short term. It strengthens memory consolidation after learning. It may slash your long-term risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease — especially if the habit starts in midlife. And none of these effects require an extreme routine. They come from something as ordinary as one or two cups a day, reliably, over time.

That’s not a minor finding. It means one of the most common daily habits in the world may also be one of the more accessible tools we have for aging with a sharp mind.

The research doesn’t say coffee is a cure-all. It doesn’t override genetics, lifestyle, or other health conditions. But as part of a thoughtful approach to brain health, that daily cup is doing more than you probably thought.