The kombucha market has grown fast over the past several years. The fizzy, tangy drinks in glass bottles promise to fix your gut, boost your immune system, and maybe even help you lose weight. But can a bottle of fermented tea really do all that?

The short answer: It’s complicated.

Let’s cut through the hype and look at what the science actually supports.

What Happens Inside the Bottle: The Science Behind the Fizz

Kombucha starts as sweetened tea. Then things get interesting.

A SCOBY — which stands for Symbiotic Culture of Bacteria and Yeast — gets added to the mix. This jellyfish-looking disc contains a community of microbes that work together. The yeast eats the sugar and produces alcohol. The bacteria then convert that alcohol into organic acids.

This process takes about 7 to 14 days. What you end up with is very different from where you started.

The final product contains acetic acid (the same acid in vinegar), gluconic acid, lactic acid, and various polyphenols from the tea. Some bottles also contain live bacteria and yeast, depending on how they’re processed after brewing.

Here’s what most articles miss: The benefits might come more from these fermentation byproducts than from the live microbes themselves.

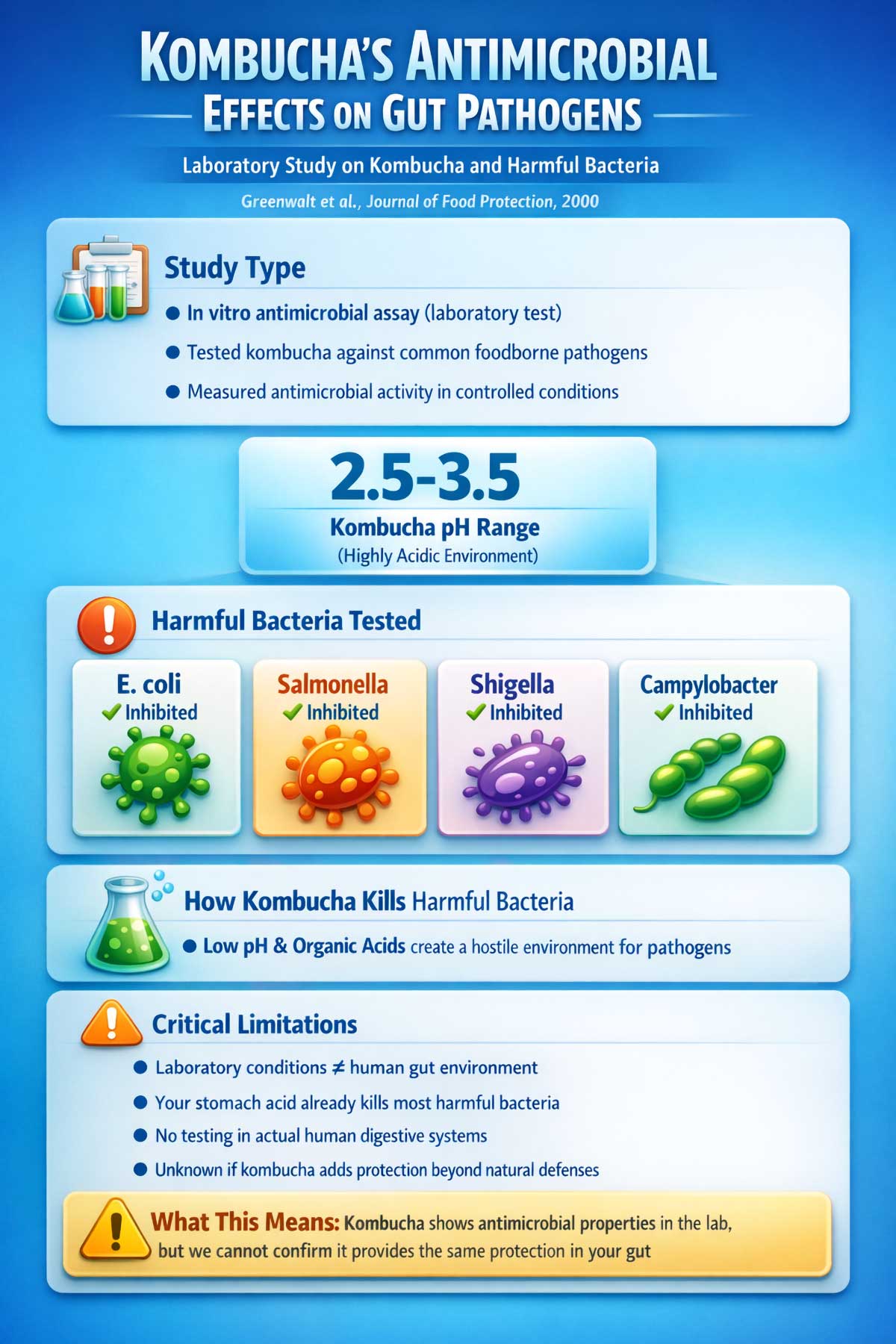

Studies show that the organic acids in kombucha create an acidic environment with a pH between 2.5 and 3.5. This acidity matters. In lab tests, kombucha has shown the ability to inhibit harmful bacteria like E. coli, Salmonella, and Shigella.

But lab tests aren’t the same as what happens in your gut.

The Gluconic Acid Mix-Up

Many kombucha advocates claim the drink contains glucuronic acid, which supposedly helps with detox. Research shows that kombucha actually contains gluconic acid, not glucuronic acid. These are different compounds. This mix-up has persisted for years in health food circles.

It matters because some of the detox claims rest on this incorrect foundation.

What the Research Actually Shows About Gut Health

Here’s what the scientific literature actually shows: Most kombucha health claims rest on test tube experiments and animal studies, not human trials.

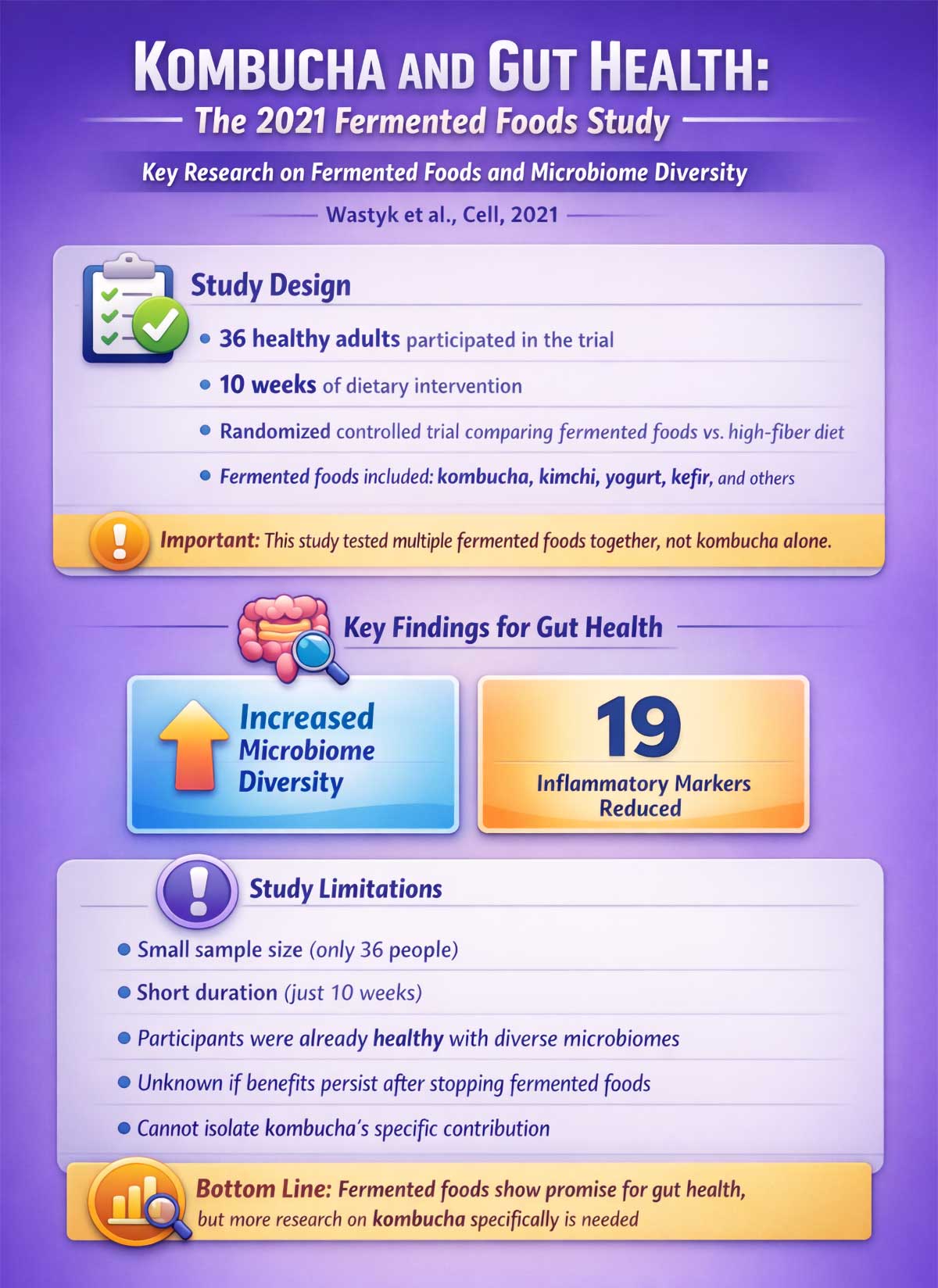

A 2021 study published in Cell examined what happens when people eat more fermented foods. Researchers had 36 healthy adults increase their intake of foods like kimchi, yogurt, kefir, and kombucha. After 10 weeks, participants in the fermented foods group showed increased gut microbiome diversity. The group also showed reductions in 19 inflammatory markers.

That sounds great. But here’s what you need to know about this study.

First, it included multiple fermented foods. Researchers didn’t test kombucha alone. We can’t say for sure that kombucha deserves the credit.

Second, the study was small — only 36 participants. It was also short-term at just 10 weeks. All participants were healthy adults with already diverse microbiomes. We don’t know if people with compromised gut health would see similar benefits. We also don’t know if the effects persist long-term or require constant consumption.

Third, the study compared two groups. One ate fermented foods. The other ate high-fiber foods. The fiber group showed different effects on inflammation. This tells us that different dietary approaches affect the gut in different ways.

Still, the findings matter. Fermented foods appear to support gut health by adding diversity to your microbiome.

Think of your gut bacteria like a garden. A garden with 50 different plant species handles pests, disease, and weather stress better than a monoculture of just 5 species. When one plant struggles, others can compensate. The same principle applies to your microbiome.

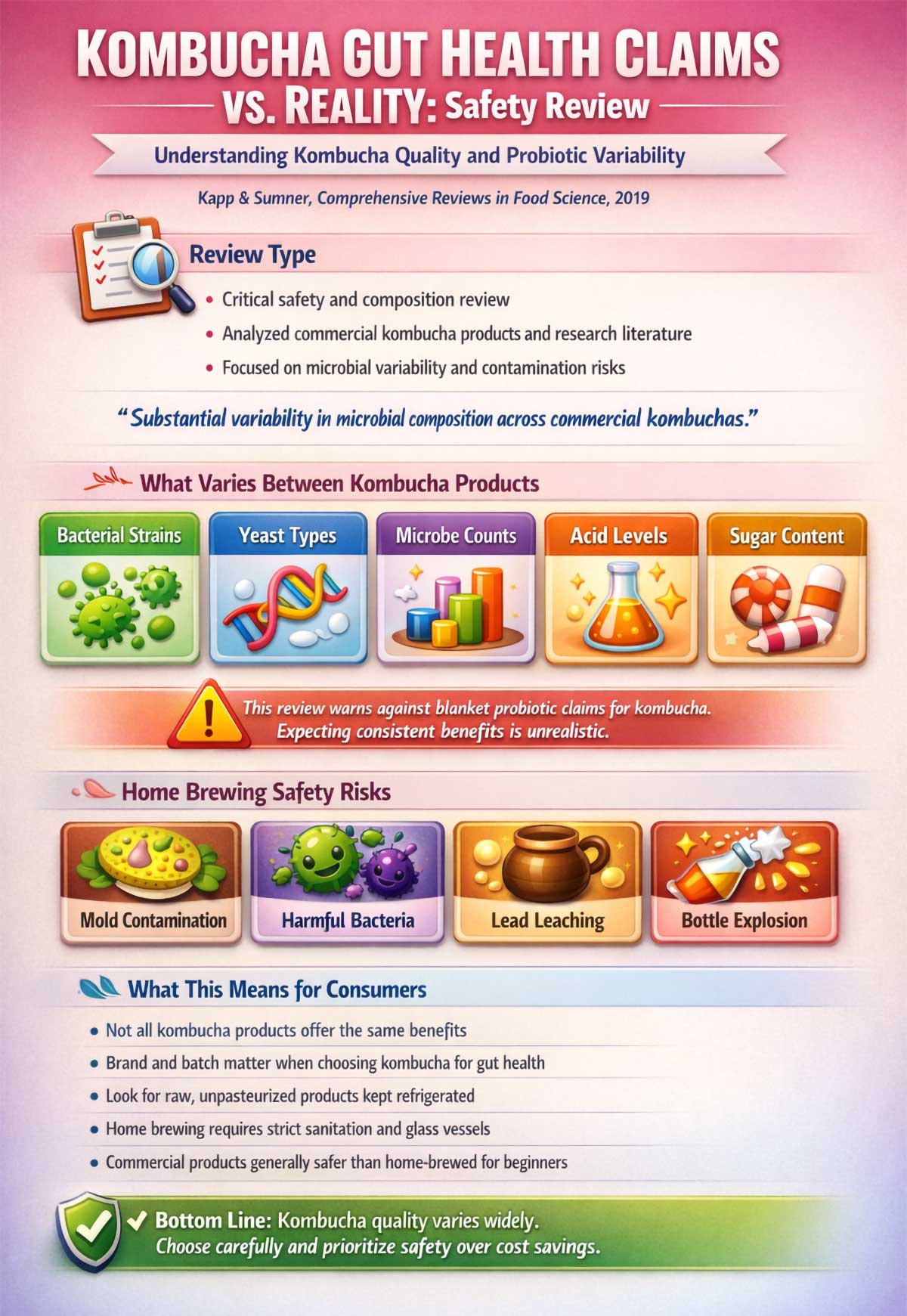

Kombucha might contribute to that diversity. The drink contains multiple strains of bacteria and yeast. Different brands and batches contain different microbes. A 2019 safety review found huge variation in the microbial makeup of commercial kombuchas.

This variability isn’t necessarily bad. It just means you can’t expect the same exact benefits from every bottle.

The Inflammation Connection

Some of the most promising research looks at fermented foods and inflammation. Chronic inflammation drives many health problems, from heart disease to autoimmune conditions.

The fermented foods study found reductions in inflammatory markers among participants who ate more fermented foods. These are the same markers doctors use to assess disease risk.

The organic acids in kombucha might play a role here. Acetic acid has been studied for its effects on blood sugar and fat storage. But most of that research used vinegar, not kombucha. The amounts of acetic acid also differ between products.

The Antimicrobial Angle

Lab studies consistently show that kombucha can kill harmful bacteria. The combination of low pH and organic acids creates an environment where pathogens struggle to survive.

A 2000 study tested kombucha against common foodborne pathogens. The results showed strong antimicrobial effects against E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter.

But your gut isn’t a petri dish. Your stomach acid already creates a hostile environment for most harmful bacteria. Whether kombucha adds meaningful protection beyond what your body already does remains unclear.

What Kombucha Definitely Doesn’t Do

Let’s talk about what kombucha can’t do, no matter what the label says.

The Detox Delusion

No food or drink detoxes your body. Your liver and kidneys handle that job 24/7. They don’t need help from fermented tea.

Some kombucha marketers claim the drink supports liver function or helps flush toxins. These claims aren’t backed by human studies.

Your liver processes everything you eat and drink. It doesn’t require special beverages to function. If your liver needed help detoxing, you’d be in the hospital, not the grocery store.

It Won’t Replace Real Food

Kombucha can’t compensate for a poor diet. No amount of fermented tea makes up for skipping vegetables and fiber.

Your gut bacteria feed on fiber from fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes. That’s what builds a healthy microbiome. Kombucha might offer a small additional benefit, but it’s not a substitute for actual food.

It’s Not a Cure

Kombucha doesn’t cure diseases or medical conditions. If you have a health problem, you need medical care, not a beverage.

Some marketing suggests kombucha can treat everything from cancer to diabetes. These claims are false and potentially dangerous.

What Kombucha Might Not Do: The Evidence Is Lacking

Beyond what kombucha definitely doesn’t do, there are claims where the evidence just isn’t there yet.

The Probiotic Problem

Many kombucha labels feature the word “probiotic” prominently. The complication is this: A true probiotic has a specific scientific definition.

The World Health Organization and the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics define a probiotic as a live microbe that, when given in the right amounts, helps health. This requires identifying the exact strain and proving it works in human trials.

Most kombucha products don’t meet this standard. The types and amounts of bacteria vary wildly. A 2019 review emphasized that blanket probiotic claims for kombucha aren’t supported by the evidence.

Most kombucha contains live cultures. But these haven’t been tested to meet probiotic standards. This doesn’t mean they’re useless. It means we can’t make specific health claims about them.

The bacteria and yeast in kombucha might offer benefits through other paths. They could produce helpful compounds during fermentation. They might interact with your gut environment in ways we don’t fully understand yet.

Plus, many brands pasteurize their product after fermentation. This extends shelf life but kills the live bacteria. You’re left with the acids and other compounds, but not the microbes.

The Weight Loss Question

Can kombucha help you lose weight? Probably not on its own.

A 2022 animal study showed that kombucha improved metabolic markers including glucose tolerance and lipid profiles in mice fed a high-fat diet. The kombucha-drinking mice gained less weight than mice who didn’t get kombucha.

But mice aren’t people. Human weight loss is complex. It involves calories, activity, sleep, stress, hormones, and dozens of other factors. No single drink will override all of that.

If kombucha helps you cut back on soda or sugary juice, great. You might see benefits from reducing your overall sugar intake. But that’s not the same as kombucha causing weight loss.

The Clinical Trial Gap

Here’s the bottom line: We need more human studies specifically testing kombucha.

Multiple reviews from 2017, 2018, and 2019 all say the same thing. The lab research looks interesting. The traditional health claims are plentiful. But large-scale, well-designed human trials are scarce.

Why does this research gap exist?

Kombucha research faces several challenges. First, the product varies wildly. Different brands, batches, and even bottles from the same batch can contain different microbes and compounds. This makes standardization for clinical trials hard.

Second, kombucha’s rise in Western markets is fairly recent. Research funding is only now catching up.

Third, studying gut health outcomes requires long-term studies with large groups of people. These are expensive and time-consuming.

The good news? Several research groups are now doing more careful studies on fermented foods, including kombucha.

Until we have that evidence, we’re mostly making educated guesses.

When Kombucha Isn’t Good for You

Not everyone should drink kombucha. And even if you can drink it, some bottles are better than others.

The Sugar Trap

Raw kombucha tastes like vinegar. Most people don’t love that flavor.

To make the drink more appealing, many brands add fruit juice after fermentation. This masks the tartness but adds sugar. Some commercial kombuchas contain as much sugar as soda.

The fermentation process does consume some of the initial sugar. But what’s added afterward stays in the bottle.

Check the label. Look for products with less sugar per serving. Some brands keep it under 7 grams per 8 ounces while still tasting good. Others load up on fruit juice and turn a health drink into liquid candy.

Acid and Your Teeth

Kombucha is acidic. Regular consumption of acidic drinks can erode tooth enamel over time.

This doesn’t mean you have to give up kombucha. Just don’t sip it slowly throughout the day. Drink it with a meal. Rinse your mouth with water afterward. Don’t brush your teeth right after drinking it — wait at least 30 minutes.

These simple steps reduce the risk to your enamel.

The Caffeine Content

Since kombucha is made from tea, it retains some caffeine. A typical 8-ounce serving contains 10 to 25 mg, depending on the tea type and brewing process.

This is less than coffee but more than decaf. If you’re sensitive to caffeine or watching your intake, factor this in. Drinking kombucha in the evening might affect your sleep.

The Alcohol Factor

Kombucha contains small amounts of alcohol. This happens naturally during fermentation.

By law, drinks labeled as non-alcoholic must contain less than 0.5% alcohol by volume. But fermentation can continue in the bottle, especially if it’s not refrigerated. Some bottles might end up with slightly more alcohol than the label states.

This usually isn’t a problem for most people. But it matters if you’re pregnant, avoiding alcohol for medical reasons, or in recovery from alcohol use disorder.

The Histamine Issue

Fermented foods contain histamines. Some people with histamine intolerance or mast cell issues may react poorly to kombucha.

Symptoms can include headaches, flushing, digestive upset, or skin reactions. If you notice these after drinking kombucha, you might be sensitive to histamines.

Home Brewing Risks

Making kombucha at home can save money. It can also go wrong.

Without proper sanitation, mold can grow on the SCOBY. Drinking moldy kombucha can make you sick. Contamination with harmful bacteria is also possible if you don’t follow clean brewing practices.

Another risk: using ceramic vessels. Some ceramic glazes contain lead. The acidity of kombucha can leach lead from the glaze into your drink. Stick with glass containers for brewing and storage.

How to Choose a Gut-Healthy Kombucha

Not all kombuchas are created equal. Here’s what to look for.

Check for “Raw” or “Unpasteurized”

If you want the potential probiotic benefits, you need live bacteria. That means the product can’t be pasteurized after fermentation.

Look for words like “raw,” “unpasteurized,” or “contains live cultures” on the label. These drinks should always be refrigerated.

If it’s sitting on a room-temperature shelf and it’s not in a specialized can designed to maintain live cultures, the probiotic value is probably zero.

Read the Sugar Content

More sugar isn’t better. It just makes the drink taste sweeter.

Compare labels. Some brands manage to keep sugar low while still tasting good. Others rely on sweetness to mask the vinegar taste.

The exact amount you choose depends on your overall diet and goals. Just be aware of what you’re getting.

Glass Bottles Matter

The acidity of kombucha makes plastic packaging problematic. Acids can leach chemicals from plastic over time.

Glass is the safer choice. Most quality kombucha brands use glass bottles for this reason.

Look for Sediment

Those stringy bits floating at the bottom of the bottle? That’s actually a good sign.

Sediment indicates biological activity. It means the drink contains live cultures. Some people find it off-putting, but it suggests you’re getting an active product.

Give the bottle a gentle swirl before drinking to mix it back in.

The Refrigeration Test

Real, unpasteurized kombucha needs to stay cold. Fermentation slows down in the fridge but doesn’t stop completely.

If you see kombucha on an unrefrigerated shelf outside of specially designed cans, it’s been processed to be shelf-stable. That usually means pasteurization. The flavor might be fine, but you’re not getting live probiotics.

The Final Verdict: Is It Worth the Money?

Kombucha isn’t a magic bullet. It won’t cure diseases or compensate for a poor diet.

But it might offer modest benefits as part of a balanced approach to gut health.

Think of it this way: Kombucha is a more sophisticated alternative to soda. It has less sugar than most soft drinks. It provides organic acids and possibly some beneficial bacteria. It might contribute to microbiome diversity.

That’s not nothing. But it’s also not everything the marketing suggests.

What Amount Makes Sense?

If you enjoy kombucha and want to drink it for potential gut benefits, a moderate amount makes sense. This is an editorial judgment based on the available evidence, not a medical prescription.

Many people find that 4 to 8 ounces daily works well. That’s enough to potentially see benefits without overdoing the sugar and acid.

You don’t need to drink a whole bottle in one sitting. Many 16-ounce bottles are actually meant to be two servings.

The Whole Diet Approach

Here’s what matters more than kombucha: fiber.

If you’re eating plenty of plant foods, staying hydrated, managing stress, and getting enough sleep, kombucha might offer a small additional benefit. If your diet is mostly processed foods and you’re not taking care of the basics, kombucha won’t fix that.

Build your gut health from the ground up with vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and legumes. Then add kombucha if you want.

Should You Spend the Money?

Good kombucha costs $3 to $5 per bottle. That adds up fast.

If you can afford it and you enjoy the taste, go for it. You’re probably getting some benefit, even if it’s just cutting back on less healthy drinks.

If money is tight, spend it on vegetables and whole foods first. Those have stronger evidence for gut health benefits. You can always make your own kombucha at home for much less money — just follow proper safety procedures.

Conclusion

Kombucha contains beneficial compounds. It might support gut microbiome diversity. It could help reduce inflammation. The evidence suggests modest benefits for some people.

But the research isn’t there yet to call it a medical treatment. The human trials are limited. The product quality varies widely. And many health claims go well beyond what the science supports.

If you like kombucha, drink it. Choose products with less sugar, live cultures, and glass packaging. Just don’t expect it to transform your health on its own.

Your gut thrives on variety, fiber, and overall healthy habits. Kombucha can be part of that picture. It just doesn’t need to be the whole story.