For most of human history, scientists believed the adult brain was fixed. You were born with a certain number of neurons, and that was that. Damage was permanent. Decline was inevitable. The brain you had at 30 was largely the brain you’d have at 80.

That view turned out to be wrong.

The science of neuroplasticity — the brain’s ability to physically change its structure — has rewritten what we thought was possible. And one of the most studied tools for triggering that change isn’t a drug, a surgery, or a high-tech device. It’s meditation.

The big question isn’t whether meditation affects the brain anymore. Researchers have answered that. The real questions are how it works, how fast it works, and what kind of practice produces which results.

Those answers depend on the intervention. Some findings come from structured 8-week programs that include group sessions and day-long retreats. Others come from intensive 3-day retreats. And some — genuinely surprising ones — come from brief daily sessions that nearly anyone can fit into a morning. This article covers the full range and makes clear which evidence points to which approach.

Growing Your Brain’s Processing Power: The Gray Matter Story

Think of gray matter as your brain’s computing hardware. It contains most of the neurons that process information, regulate emotion, and store memories. In regions like the hippocampus, increased gray matter density typically correlates with improved memory and emotional regulation — though the relationship between brain structure and function is complex and varies by region.

A landmark 2011 study by Hölzel and colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital gave us some of the clearest evidence yet for what a structured meditation program does to gray matter. The researchers enrolled 16 healthy adults in an 8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program — a format that included weekly 2.5-hour group sessions and a day-long retreat, with formal home practice in between. Participants reported practicing at home for an average of 27 minutes per day. Before and after MRI scans showed something striking: gray matter density appeared to increase in four key brain regions — the left hippocampus, the posterior cingulate cortex, the temporo-parietal junction, and the cerebellum.

Each of those regions does something specific.

The Hippocampus: Your Brain’s Memory Hub

The hippocampus sits at the center of learning and memory. It helps you form new memories, connect past experiences to present ones, and regulate your emotional responses. Chronically elevated cortisol — the hallmark of ongoing stress — can be toxic to hippocampal neurons over time, and stress-related hippocampal shrinkage is well-documented in the research.

The Hölzel study found denser gray matter in the left hippocampus after 8 weeks of MBSR. More density appears to support more neural connections — and more connections tend to support better memory, better learning, and better emotional balance. The evidence is correlational, but the pattern across multiple studies is consistent enough to take seriously.

The Posterior Cingulate Cortex and Temporo-Parietal Junction

These two regions handle different but related tasks. The posterior cingulate cortex is linked to self-referential thinking — how you think about yourself and your place in the world. When it’s overactive, it tends to fuel rumination and mind-wandering. Meditation appears to quiet it down and, over time, may make it more efficient.

The temporo-parietal junction (TPJ) is involved in perspective-taking and empathy. It helps you understand that other people have thoughts and feelings different from your own. The gray matter increases seen in the TPJ after MBSR training may help explain why long-term meditators often report feeling more connected to others and less reactive in conflict.

A 2014 meta-analysis by Fox and colleagues strengthened these findings considerably. Looking across 21 neuroimaging studies involving roughly 300 meditation practitioners, the researchers found consistent structural changes in eight brain regions across different meditation styles. These included the frontopolar cortex, sensory cortices, the insular cortex, the hippocampus, and the anterior and mid-cingulate cortex. The consistency across independent research teams is one of the more compelling aspects of the meditation-brain literature.

Downsizing The Fear Center: What Happens To The Amygdala

The amygdala is the brain’s alarm system. It detects threats — real or imagined — and triggers the fight-or-flight response. In a world with actual predators, that’s essential. In modern daily life, where “threats” are often emails, traffic, and social pressure, a hair-trigger amygdala creates real problems.

Chronic stress keeps the amygdala in a near-constant state of activation. It also appears to make the amygdala physically larger and more reactive. The result is anxiety, poor sleep, irritability, and difficulty thinking clearly.

Meditation appears to shift this balance in a measurable way — though the speed of that shift depends heavily on the intensity of the practice.

A 2015 study by Taren and colleagues examined 35 job-seeking adults — a population under significant psychological stress. These participants completed an intensive 3-day mindfulness meditation retreat. This is a fundamentally different format from brief daily home practice. A retreat like this typically involves 8 to 10 hours of guided practice per day — roughly 24 to 30 hours of total meditation compressed into three days. After the retreat, researchers detected changes in the resting-state functional connectivity between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. In plain terms: the amygdala appeared less likely to hijack behavior, and the prefrontal cortex — the rational, deliberate part of the brain — showed greater influence over the stress response.

What makes this finding stand out is the follow-up data. Those functional connectivity changes held at a 4-month check-in. Participants weren’t attending intensive retreats for those four months. Yet the changes persisted — suggesting that a compressed, intensive meditation experience may produce durable shifts in stress-circuit function, particularly for people already under sustained pressure.

How the Prefrontal Cortex Learns to Take the Wheel

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is where planning, decision-making, and impulse control live. It’s also the region that can override the amygdala’s alarm signals when a perceived threat isn’t actually dangerous. Scientists sometimes call this “top-down regulation” — the PFC essentially tells the amygdala to stand down.

Regular meditation appears to strengthen that connection over time. The PFC becomes better at communicating with the amygdala, and the brain may get faster at switching off the stress response once a threat has passed. For people in high-pressure environments — demanding careers, unstable circumstances, caregiving roles — that’s not just a wellness benefit. It’s a functional shift in how the brain manages pressure.

Faster Signals: The Role Of White Matter

Most articles about meditation and brain health focus on gray matter. But gray matter doesn’t work alone. It relies on white matter — the network of insulated fibers that carry signals between brain regions — to communicate efficiently. If gray matter is the hardware, white matter is the wiring.

Better-organized white matter means faster, more reliable communication across the brain.

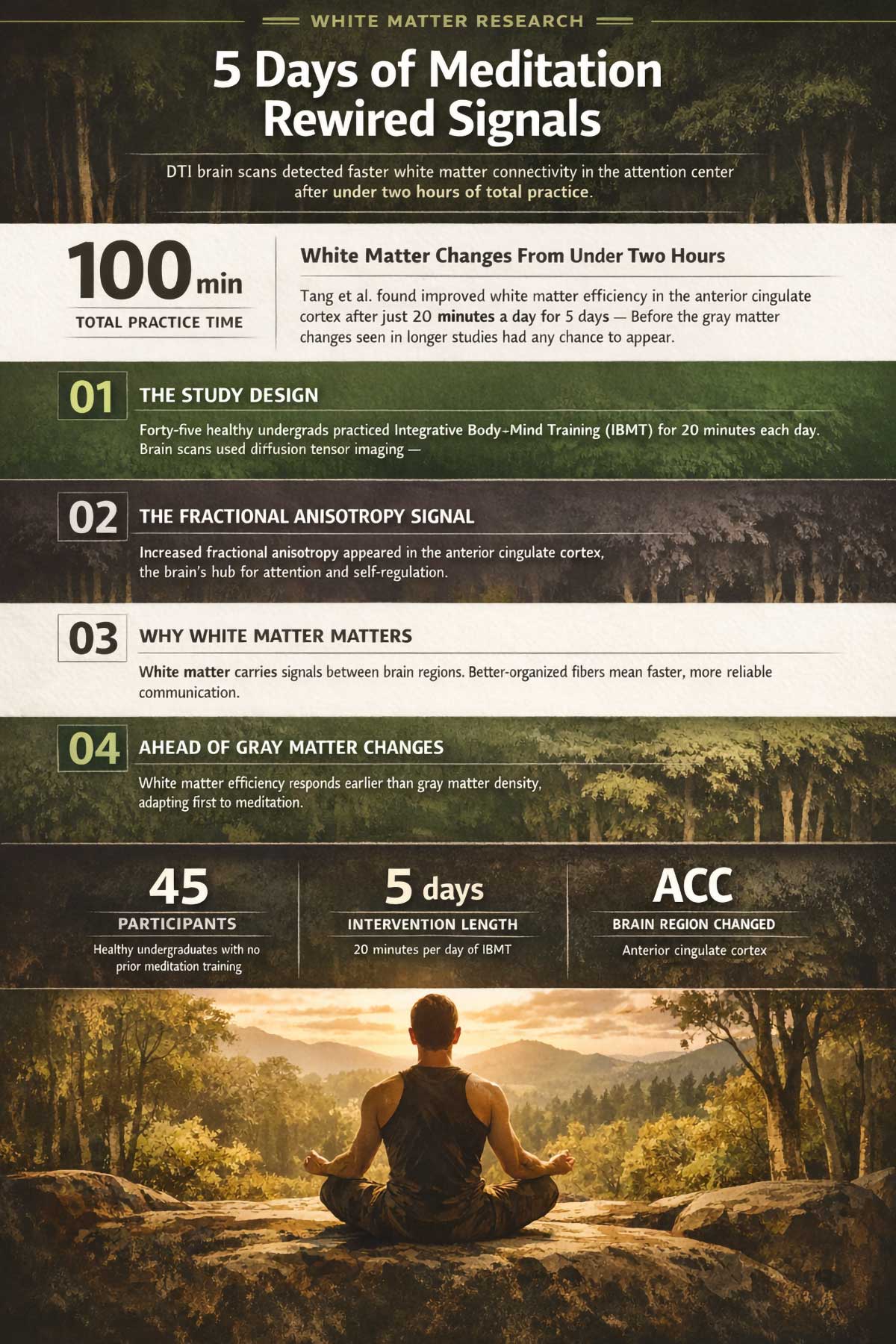

A 2010 study by Tang and colleagues tested 45 healthy undergrads using a type of meditation called Integrative Body–Mind Training (IBMT). Participants practiced for 20 minutes a day for 5 consecutive days — roughly 100 minutes of total practice. Using a brain imaging technique called diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), the researchers measured white matter changes in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a region tied to attention and self-regulation.

The result: improved white matter efficiency and increased “fractional anisotropy” — a measure of how organized and intact white matter fibers are — in the ACC after under two hours of total practice. That’s a meaningful early signal. The brain’s communication structure appears to begin responding before the more widely-discussed gray matter changes take hold.

What Attentional Control Actually Feels Like

The anterior cingulate cortex, where those white matter changes appeared, plays a major role in what researchers call attentional control — your ability to focus, filter out distractions, and stay on task. When white matter in the ACC becomes more efficient, thinking under pressure tends to get clearer and sustained focus becomes easier to hold.

This connects to a separate line of cognitive research — one we’ll return to shortly — showing that consistent daily practice also appears to reduce the “attentional blink,” a gap in perception where the brain briefly loses track of information during rapid tasks. Better-organized white matter may be part of why that gap shrinks.

The Age-Defying Brain: Holding Back The Clock

The brain doesn’t just change with meditation. It changes with age too — and not in a good direction. Starting in the 30s, the prefrontal cortex naturally loses cortical thickness. By middle age, measurable structural decline has already begun at the cellular level, even when it isn’t yet obvious in daily function.

Cortical thickness matters. Thicker cortex in key regions correlates with sharper attention, better working memory, and faster processing speed. As the cortex thins, those abilities tend to follow.

A 2005 study by Lazar and colleagues at Harvard compared 20 experienced meditators — who averaged 9 years of regular practice — to 15 non-meditating controls. Using structural MRI, the researchers measured cortical thickness across multiple brain regions.

The meditators showed greater cortical thickness in two areas in particular: the prefrontal cortex and the right anterior insula. More striking was what the data showed about aging. Cortical thickness typically declines with age in a predictable way. In the meditation group, that thinning appeared significantly offset — with older meditators showing cortical thickness measurements comparable to those of people considerably younger. This suggests that sustained practice may act as a long-term protective factor against age-related structural decline. It’s worth noting that this was a cross-sectional study: the meditators and controls were compared at a single point in time, which means other factors — such as the kind of person drawn to long-term practice — can’t be entirely ruled out.

The Insula: Staying Connected to Your Own Body

The right anterior insula — one of the key regions showing greater cortical thickness in Lazar’s meditators — handles interoception: the brain’s ability to sense internal body states like heart rate, breathing, hunger, and tension. As people age, interoceptive awareness often dulls, contributing to poorer body awareness and weaker emotional self-regulation.

Long-term meditators appear to retain this ability at higher levels. The insular cortex stays thicker. The connection to the body stays cleaner. This may help explain why experienced meditators often describe a stronger sense of internal calm — they may be more accurately sensing what’s happening inside them rather than operating on guesswork.

What Brief Daily Practice Can Do

The studies discussed so far involve either comprehensive structured programs or years of committed practice. That’s worth naming clearly, because it shapes what the findings can actually tell us. But there is a separate and genuinely encouraging body of evidence focused on shorter, more accessible forms of daily meditation.

A 2013 study by Kang and colleagues enrolled 49 adults who had never meditated before. They practiced for an average of 13 minutes a day over 8 weeks. Some sessions were as short as 5 minutes; others reached 16 minutes. There were no group sessions or retreats involved — just brief, consistent daily practice.

By the end of 8 weeks, participants showed meaningful improvements in attentional control and cognitive flexibility. They were better at switching between tasks, maintaining focus, and recovering attention after distraction. The study also measured the “attentional blink” effect — the brief window during rapid information processing when the brain struggles to register a second piece of input close in time to a first. Regular brief meditation appeared to reduce that window. The brain moved through information more efficiently without losing its grip.

This approach doesn’t replicate every finding seen in intensive MBSR programs or long-term practitioner studies. But it does offer real evidence that cognitive gains are possible without a major time commitment — and that consistency appears to matter more than session length.

Why Regularity Appears to Outweigh Duration

The brain adapts to repeated, regular input. A training effect that shows up from 20-minute daily sessions over 5 days (Tang et al.) and from 13-minute daily sessions over 8 weeks (Kang et al.) suggests the brain responds to the signal of consistent practice — not just to total accumulated hours.

Think of it like building physical endurance. A short run every day tends to build more reliable fitness than a single long run once a week. The regular input keeps the adaptation process active. The same logic appears to apply to attentional training through meditation.

Putting It Together: Three Approaches, Three Timelines

Rather than a single path from beginner to advanced practitioner, the research points to three distinct approaches — each with its own evidence base and realistic time expectations. Understanding which findings come from which approach helps set honest expectations.

Brief Daily Practice (5–16 minutes/day)

The Kang and Tang studies sit in this category. White matter changes in attentional regions appear within days of consistent short sessions. Cognitive flexibility and attentional control improve meaningfully over 8 weeks of daily sessions averaging 13 minutes. This approach has the lowest barrier to entry and the most direct evidence that a modest, consistent time investment produces real cognitive results — particularly in attention and processing speed.

Structured Programs (8-week MBSR and similar formats)

The Hölzel study and the broader Fox meta-analysis represent this tier. These programs combine group instruction, retreat experiences, and daily home practice. The total time investment is substantially higher than brief daily sessions alone. The brain changes documented at this level — apparent gray matter density increases in the hippocampus, posterior cingulate cortex, and temporo-parietal junction — represent structural shifts tied to memory, emotional regulation, and self-awareness. For people who can access this kind of program, the evidence is strong.

Intensive and Long-Term Practice

The Taren retreat study and Lazar’s long-term practitioner research occupy this space. An intensive 3-day retreat, with 24 to 30 hours of total practice, appears to produce lasting shifts in amygdala connectivity — particularly meaningful for people under sustained high stress. And years of consistent practice appear associated with structural preservation of the prefrontal cortex and insula against age-related thinning. These findings are the most striking in the literature, but they reflect levels of practice that take real commitment to reach.

It’s also worth noting that most studies in this area involve relatively small samples, and findings continue to be tested across broader and more varied populations. Individual responses will vary. These are population-level trends, not guarantees — but they reflect a pattern consistent enough across independent research teams to be taken seriously.

The good news: you don’t need to start at the most intensive level. Many people begin with brief daily practice, build consistency, and work toward structured programs over time. The brain appears to keep responding at each level of investment.

Conclusion

The idea that paying quiet attention to your breath could physically change your brain used to sound like wishful thinking. It doesn’t anymore.

Gray matter density in regions tied to memory, empathy, and self-awareness appears to increase after structured 8-week meditation programs. The amygdala’s grip on stress responses appears to loosen after intensive retreat experiences, with changes that hold for months. White,atter in a key attentional hub appears to become more efficient after under two hours of practice spread over five days. And brief daily sessions averaging 13 minutes appear to produce measurable cognitive gains within 8 weeks — no retreat required.

Meditation isn’t just a philosophy. It’s a practice with a biological mechanism. The “rewiring” isn’t borrowed from self-help culture — it’s a reasonable description of measurable structural change in living tissue, documented across multiple independent research teams.

Your brain is plastic. The research is clear that it responds to how you use it. The level of practice you can commit to will shape which changes you’re likely to see — but there appears to be a meaningful return at every level of engagement.