For the past two decades, neuroscientists have pointed high-powered imaging machines — fMRI and MRI scanners — directly at the sleep-deprived brain. What they found isn’t pretty. It isn’t abstract, either. These scans show real, physical changes happening inside your skull when you cut sleep short. Changes to structure. Changes to connectivity. Changes that look, in some cases, like years of premature aging.

This isn’t about willpower or discipline. It’s about wiring. When you skip sleep, your brain’s internal connections literally shift — and the consequences show up in your mood, your decisions, your appetite, and even the physical size of your brain over time.

Here’s what the science actually shows.

The Emotional Brake Line Gets Cut

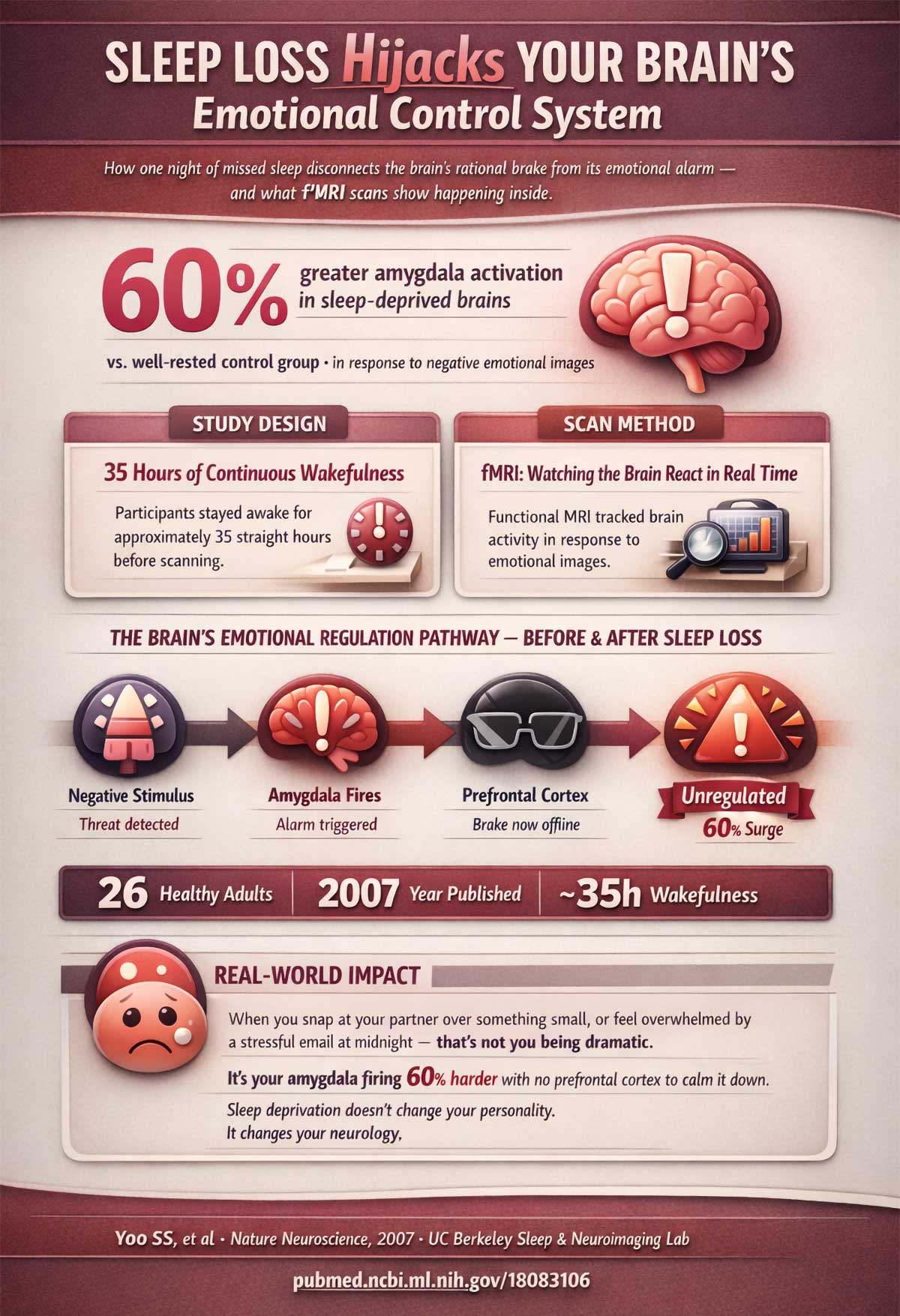

Your brain has two key players in emotional control. The amygdala is the alarm system — it fires up when you see something threatening or upsetting. The medial prefrontal cortex acts like a brake pedal, keeping that alarm from going haywire.

When you’re well-rested, these two regions work as a team. The prefrontal cortex tells the amygdala to calm down. You feel the emotion, process it, and move on.

Sleep deprivation snaps that connection.

In a landmark 2007 study, researchers at UC Berkeley led by Yoo and colleagues scanned the brains of 26 healthy adults after roughly 35 hours of continuous wakefulness. The results were striking. Sleep-deprived brains showed 60% greater amygdala activation in response to negative images compared to well-rested participants. More alarming, the functional link between the amygdala and the medial prefrontal cortex had essentially disappeared. The brake pedal stopped working.

That’s why you snap at your partner over something small. That’s why a stressful email feels catastrophic at midnight. You’re not being dramatic — you’re neurologically unregulated. Your emotional alarm is blaring with nothing to quiet it down.

Your Brain Physically Shrinks Over Time

A bad night messes with your emotions. But what happens when poor sleep becomes a pattern? The brain doesn’t just malfunction — it starts to physically change.

A 2012 study out of Japan, led by Taki and colleagues, tracked 290 healthy adults using MRI over three years. The team measured gray matter volume — the tissue that houses most of your brain’s processing power — and compared it against sleep habits. Every one-hour reduction in daily sleep duration was linked to an annual gray matter decline of roughly 0.59%, particularly in the frontal regions of the brain.

That might sound small. Compound it over five or ten years and the picture becomes deeply concerning. The structural loss mirrors what you’d expect to see in someone years older — not from genetics or disease, but from not sleeping enough. The researchers noted that while the association between sleep duration and gray matter loss is strong, other factors tied to poor sleep — like stress or underlying health conditions — may also play a role.

This point sharpens further when you add findings from Dai and colleagues in 2020. Their structural MRI study of 775 adults found that people with chronic insufficient sleep showed cortical thinning and reduced subcortical volumes — meaning both the outer layer of the brain and its deeper internal structures were affected. It wasn’t one region taking the hit. It was broad and widespread.

The Risk Radar Goes Dark

Here’s where sleep deprivation gets quietly dangerous in everyday life.

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex is the part of your brain that weighs consequences. It runs a constant background check: Is this a good idea? What could go wrong? Is the reward worth the risk? When it’s working properly, it keeps you from making impulsive or harmful choices.

Sleep loss dials it down.

A 2010 review by Killgore examined multiple fMRI and behavioral studies and found consistent evidence that sleep deprivation impairs the function of prefrontal regions tied to moral judgment, emotional regulation, and risk assessment. When these regions go quiet, the brain loses its ability to accurately predict negative outcomes.

The real-world fallout is significant. Fatigued drivers who underestimate their own impairment. Tired traders making reckless calls. Exhausted parents making poor safety decisions. It’s not recklessness by choice — it’s a brain running without its safety checks.

A 2017 neuroimaging meta-analysis by Krause and colleagues added important weight to this picture. Pulling together 18 studies covering 335 participants across controlled lab settings — where sleep deprivation was experimentally induced under careful monitoring — the research team identified consistent patterns of reduced activity in prefrontal regions after sleep loss. At the same time, areas tied to emotional processing became more active. The brain wasn’t just quieter in the wrong places. It was louder in others, amplifying reactive responses while suppressing rational ones.

The Junk Food Hijack

Here’s something worth saying upfront: if you crave chips, cookies, and fast food after a poor night’s sleep, that’s not a lack of discipline. It’s your brain chemistry doing something very deliberate.

In a 2011 study, Gujar and colleagues scanned 29 healthy adults using fMRI after a full night of sleep deprivation. The focus was the mesolimbic reward system — specifically the striatum and insula, which process pleasure and reward signals. The sleep-deprived brain showed amplified responses to rewarding stimuli, particularly high-calorie foods. The reward circuitry fired harder, and without a functioning prefrontal cortex to moderate the impulse, the pull toward sugar and fat became nearly impossible to resist.

Think of it this way: your brain is running low on fuel. It knows dopamine — the feel-good signal tied to food and reward — can give it a quick boost. So it dials up the craving and dials down the part of you that would normally say “no thanks.” The result is a neurochemical demand, not a personal failing.

This is one key reason chronic sleep deprivation is tied to weight gain and poor dietary choices. The brain isn’t broken — it’s doing exactly what it’s wired to do when it’s exhausted. Unfortunately, that means steering you straight toward the snack aisle.

The Communication Cables Start Fraying

When people talk about brain health, they usually focus on gray matter — the neurons doing the thinking. But there’s another layer that rarely gets attention: white matter. These are the long, insulated cables that connect different brain regions to each other. Without them, signals can’t travel efficiently. Communication breaks down.

Sleep deprivation hits white matter too.

A large 2020 study by Sexton and colleagues analyzed data from nearly 4,000 adults through the UK Biobank using a technique called Diffusion Tensor Imaging, which maps the microscopic structure of white matter tracts. People who reported sleep problems showed widespread differences in white matter integrity compared to those who slept well.

Think of white matter as a highway system. Healthy white matter means smooth, fast connections between regions. Damaged white matter is like a highway full of potholes — traffic still moves, but slowly, erratically, and with far more effort. The practical effect is what most people recognize as “brain fog” — that thick, sluggish feeling where thoughts won’t connect and processing simple information feels like wading through mud. It’s not in your head in the figurative sense. It’s physically, structurally in your head.

The Trash Doesn’t Get Taken Out

There’s one more thing happening during sleep that most people never hear about — and it may be the most consequential of all.

During deep sleep, the brain runs its own waste-clearance system, known as the glymphatic system. This network flushes out toxic proteins that build up during waking hours, including beta-amyloid — a substance directly tied to Alzheimer’s disease. When you cut sleep short, that biological housekeeping doesn’t happen. The waste accumulates.

This connects sleep deprivation to something far beyond mood and memory. Researchers increasingly link chronic poor sleep to long-term neurodegenerative risk. The nightly cleanup your brain depends on gets skipped, night after night, with consequences that may not show up for years — but show up they do.

The Developing Brain Pays a Steeper Price

These effects in adults raise an urgent question: what happens to brains that haven’t finished developing yet?

Sleep isn’t just rest for a growing brain. It’s the primary window during which the brain builds, prunes, and organizes itself. Cut that window short, and the consequences appear in the structure itself.

A major 2018 study by Chen and colleagues drew on data from the Generation R Study, tracking nearly 9,846 children between ages 9 and 12. Using MRI, researchers measured total brain volume and broke it down into gray and white matter. The result was direct: children who slept fewer hours had measurably smaller total brain volumes, including reductions in both gray and white matter.

This goes beyond school performance or mood — though both are affected. This is about the physical architecture of the brain during the years it’s most actively building itself. Sleep, for a child, is construction time. Cutting it short doesn’t just delay the work. It reduces what gets built.

What Happens When You Start Sleeping Again

Here’s the part worth holding onto.

The brain has a genuine capacity to recover. After a single night of poor sleep, one or two nights of solid recovery sleep can restore much of the lost functional connectivity and emotional regulation. The amygdala calms back down. The prefrontal cortex reconnects. The risk radar comes back online.

The picture gets more complicated with chronic, long-term sleep loss. Research suggests that weeks to months of consistent sleep can improve cognitive function for those carrying significant sleep debt — but some structural changes may be slower and harder to fully reverse. Years of sleeping five to six hours a night may leave lasting differences in white matter and gray matter that don’t completely disappear, even with sustained good sleep. The pattern matters as much as any single night.

The takeaway isn’t complicated, though. Sleep is when your brain consolidates memories, runs its glymphatic cleanup crew, repairs connections, and maintains itself at the most basic structural level. An extra hour of sleep is an investment in gray matter volume, white matter integrity, and emotional stability.

Think of it as the maintenance window your brain requires to run properly. Miss enough of those windows, and the system doesn’t just slow down. It starts to degrade — quietly, invisibly, measurably — in ways that brain scans are now making impossible to ignore.

Your brain is worth the hours — seven to nine for most adults. Give it what it needs.