Most people think of peanuts as junk food. A salty snack you grab at a ball game. Something to feel guilty about. But what if that handful of peanuts sitting in your pantry was quietly doing your heart a favor?

Real science backs this up. And the results are more striking than most people expect.

The 21-Day Heart Reset

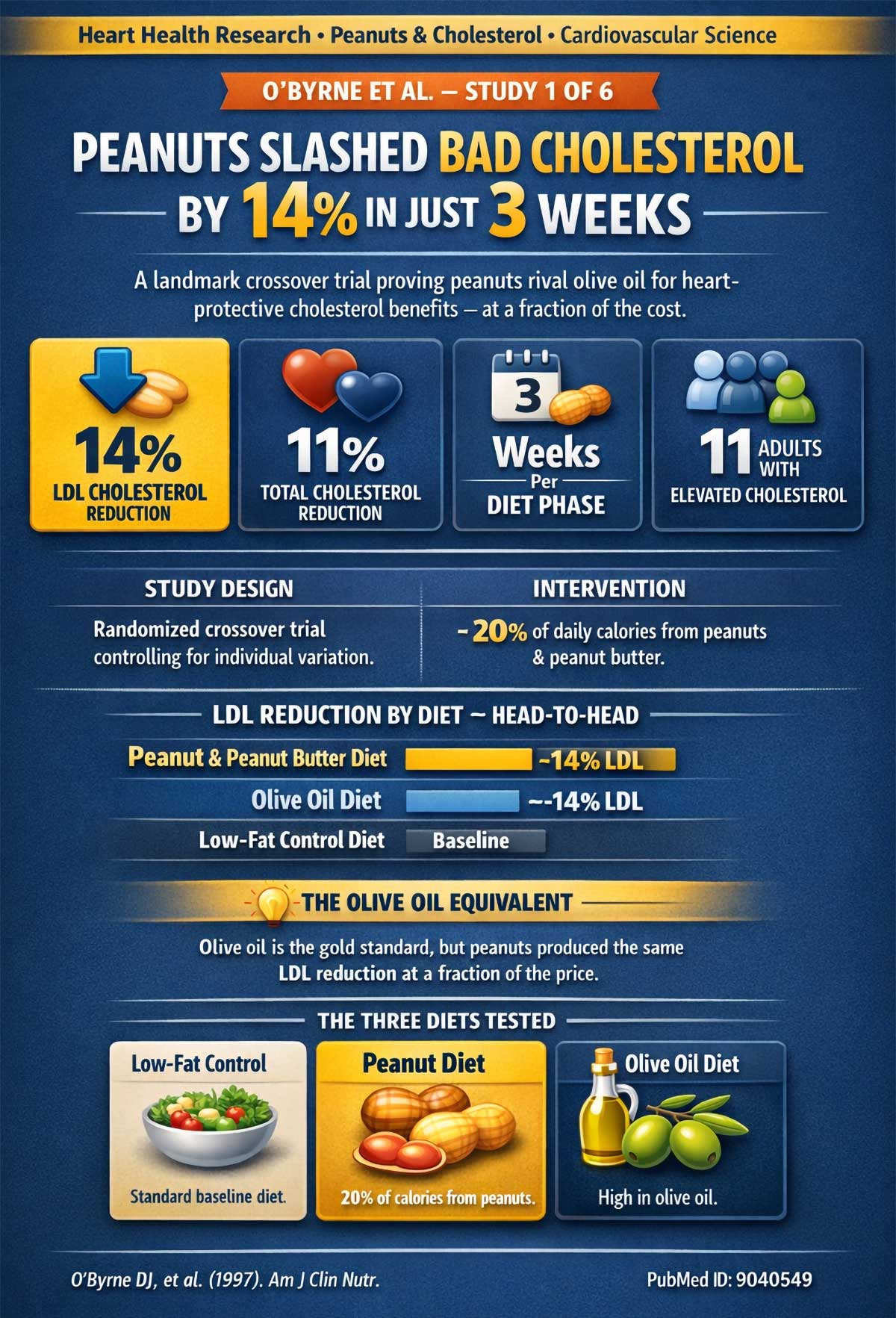

In 1997, a team of researchers set out to test whether peanuts could hold their own against one of the most praised heart-healthy foods on the planet: olive oil.

The study, led by O’Byrne and colleagues, took 11 adults with elevated cholesterol and ran them through three different diets. One was a standard low-fat diet. Another was rich in olive oil. The third was built around peanuts and peanut butter—about 20% of daily calories. Each phase lasted three weeks.

The peanut diet cut LDL (“bad”) cholesterol by 14%. Total cholesterol dropped 11%. The results matched the olive oil diet almost exactly.

Three weeks. A handful of peanuts a day. That’s it.

The study was small—11 participants—but it wasn’t alone. Multiple independent research teams have since replicated these findings with larger groups, which we’ll get to shortly.

This isn’t a minor footnote in nutrition science. A 14% LDL reduction is clinically meaningful. Many doctors consider a 10% drop worth celebrating. And here it happened in less time than it takes to finish a month of medication.

Why Peanuts Work: Inside the Chemistry

So what’s actually happening inside your body when you eat peanuts regularly? It comes down to a few key compounds working together.

Plant Sterols: The Cholesterol Blockers

Peanuts contain plant sterols—natural compounds that look a lot like cholesterol at the molecular level. When you eat them, they compete with cholesterol for the same absorption spots in your gut. Cholesterol loses that competition and gets pushed out of the body before it can enter your bloodstream.

It’s a straightforward physical mechanism. Less cholesterol absorbed means lower LDL levels. No exotic chemistry required.

The Oleic Acid Factor

Peanuts are rich in monounsaturated fat, specifically oleic acid. This is the same fat that gives olive oil its heart-healthy reputation. It helps lower LDL while leaving HDL (“good”) cholesterol untouched—exactly the kind of shift your cardiologist wants to see.

To put this in perspective: peanuts are about 50% fat by weight, but the majority of that fat is the monounsaturated and polyunsaturated kind. The saturated fat content is actually lower than most people assume. A one-ounce serving has roughly the same favorable fat profile as a tablespoon of olive oil.

Fiber That Pulls Its Weight

Beyond fat, peanuts contain soluble fiber. Soluble fiber binds to cholesterol in the digestive tract and helps carry it out of the body. It also slows how quickly food is digested, which matters for blood sugar control—another key piece of heart health.

Beyond Cholesterol: What Happens to Your Blood Vessels

Most articles about peanuts and heart health stop at cholesterol numbers. But there’s another layer here that rarely gets mentioned—and it may be just as important.

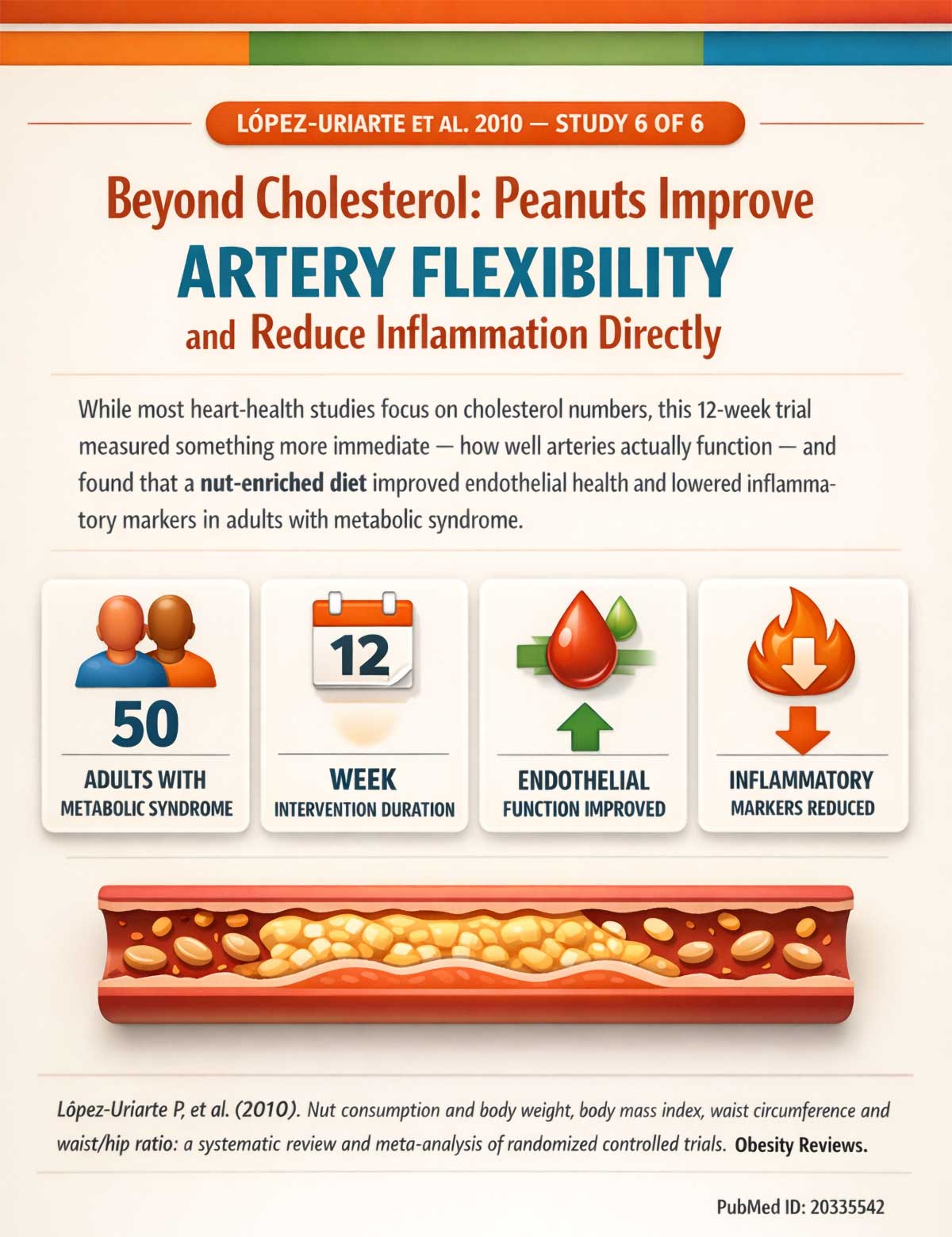

Your arteries aren’t rigid pipes. They’re living tissue. Healthy vessels expand and contract depending on what your body needs. This flexibility is called endothelial function, and it’s a critical marker of cardiovascular health. When your vessels stop dilating properly, it raises blood pressure and increases the risk of clotting.

Peanuts are one of the richest food sources of L-arginine—an amino acid your body uses to produce nitric oxide. Nitric oxide tells blood vessels to relax and open up. Think of it as the body’s natural signal to keep arteries flexible.

Research supports this directly. A 2010 study by López-Uriarte and colleagues followed 50 adults with metabolic syndrome for 12 weeks. Those who ate a nut-enriched diet showed real improvements in endothelial function and lower levels of inflammatory markers compared to the control group. In other words, their arteries were working better.

Post-Meal Protection

Here’s something even more specific: eating peanuts alongside a high-fat meal can blunt the arterial stiffening that typically follows a heavy meal. After eating, your arteries normally tighten somewhat—a natural but not ideal response. Peanuts seem to soften that reaction.

This “post-meal” protection is something few heart-health foods can offer. It’s a real-time benefit, not just a long-term trend.

The Weight Gain Myth—Put to Rest

A lot of health-conscious people avoid peanuts for one reason: calories. At about 160 calories per ounce, peanuts aren’t a light snack. So the concern is valid on the surface.

But the research tells a different story.

A 2003 study by Alper and Mattes tracked 15 healthy adults for eight weeks. Participants added peanuts to their regular diet—about 89 grams per day for men and 72 grams per day for women. That’s an extra 500 calories a day.

By the end of eight weeks, the participants had gained zero net weight.

How? Two reasons.

The Satiety Effect

Peanuts are packed with protein and fiber. This combination suppresses hunger hormones more effectively than carbohydrate-heavy snacks. People who ate peanuts naturally ate less elsewhere in their diet. They felt full longer, so they made up for the calories in other meals without even realizing it.

Incomplete Absorption

Not all peanut calories actually make it into your bloodstream. Peanuts have a cellular structure that resists full digestion. Some of the fat remains trapped inside plant cells and passes through the body without being absorbed. Studies suggest that a meaningful portion of peanut calories—estimates range from 10–15% or more—aren’t fully absorbed, particularly when peanuts are eaten whole rather than as butter.

So the caloric math you see on a nutrition label slightly overstates what your body actually takes in.

Confirmation From Independent Research

The original O’Byrne study wasn’t a fluke.

A 2008 study by Kris-Etherton and colleagues tested five different diets in 22 adults with moderate high cholesterol over 24 days each. The peanut-enriched diets reduced LDL by 10–14% and total cholesterol by 7–10% compared to a typical American diet. The benefits matched those of other high-oleic acid diets.

A separate 2004 trial by Griel and colleagues, also 24 days with 22 adults, found the same LDL drop—10–14%—plus a significant reduction in apolipoprotein B, a protein that carries harmful cholesterol particles in the blood. Apolipoprotein B is considered by many cardiologists to be a more precise predictor of heart risk than LDL alone. That peanuts moved this marker confirms the benefit goes deeper than surface-level cholesterol numbers.

30 Years of Data: The Long-Term Picture

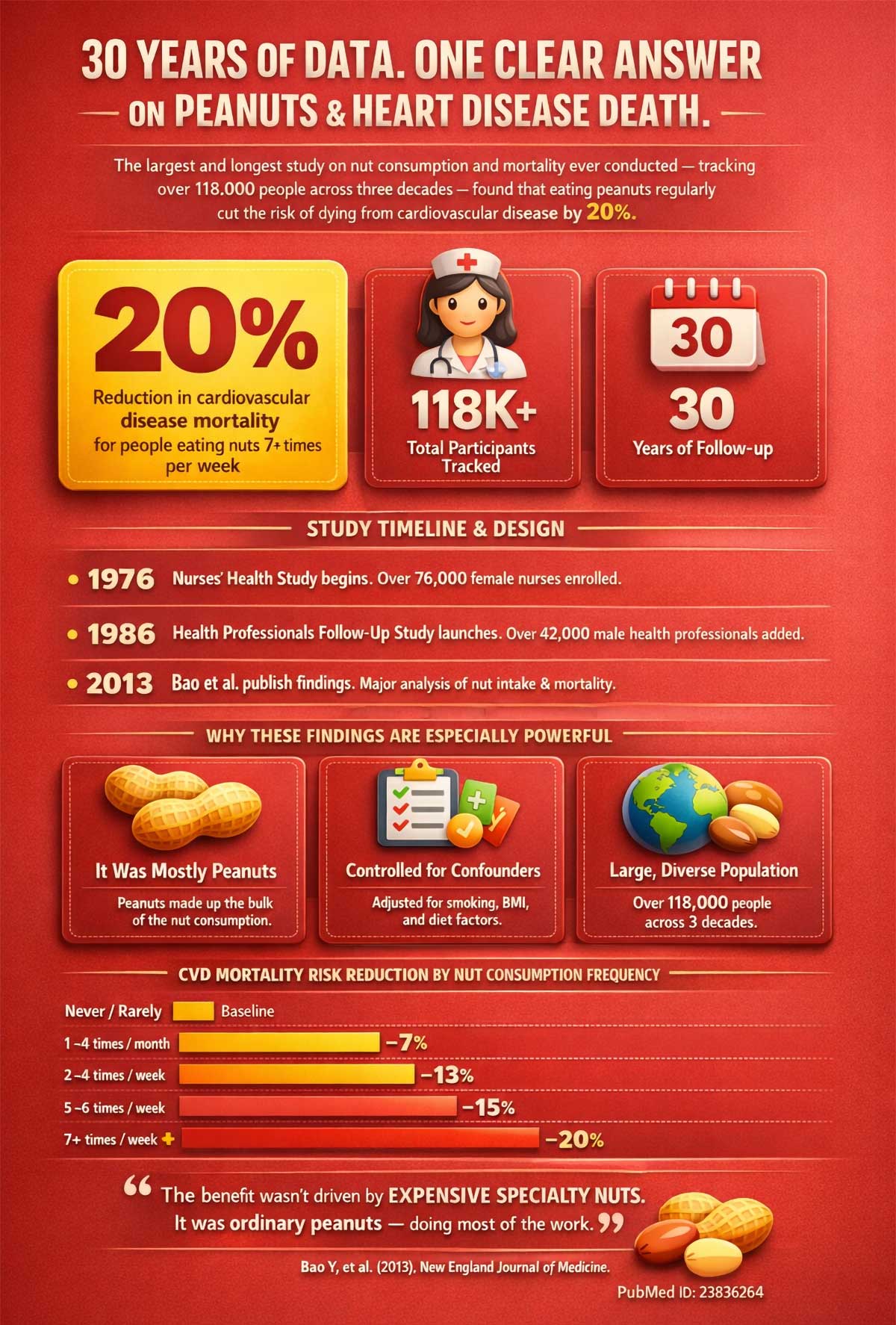

Short-term studies are useful. But what really matters is whether these benefits translate into living longer.

The Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study answered that question. Together, they tracked over 118,000 people for up to 30 years—one of the longest dietary studies ever conducted. The 2013 analysis by Bao and colleagues found that people who ate nuts at least seven times a week had a 20% lower rate of death from cardiovascular disease.

Critically, peanuts made up the majority of nut intake in that study. This wasn’t a result driven by expensive cashews or exotic specialty nuts. It was ordinary peanuts—the most affordable nut in the grocery store—doing most of the work.

Finding the Right Amount

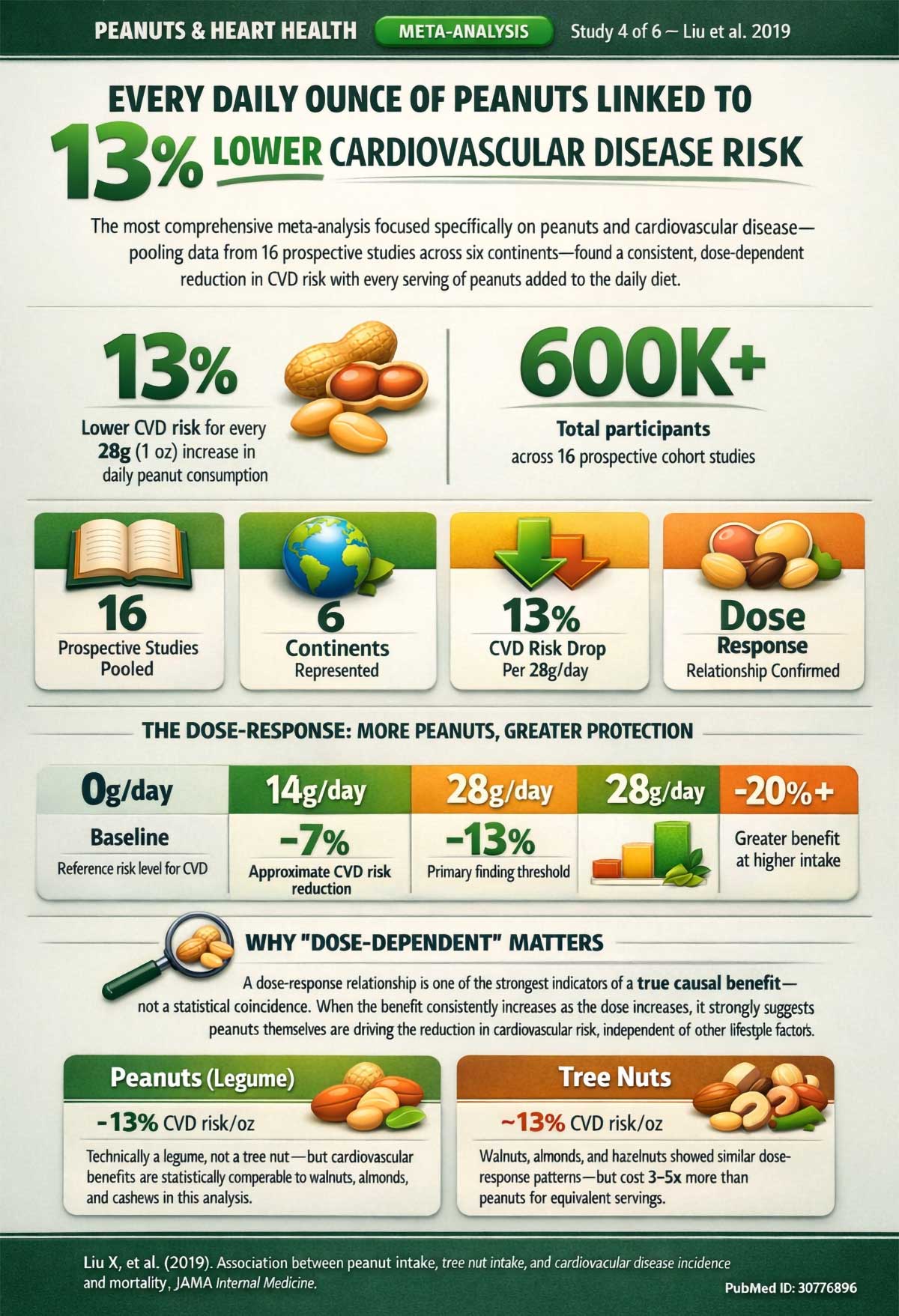

A 2019 meta-analysis by Liu and colleagues brought even more precision to the picture. Researchers pooled data from 16 prospective cohort studies covering over 600,000 participants. They found that each 28-gram (roughly one ounce) increase in daily peanut consumption was associated with a 13% lower risk of cardiovascular disease. The relationship was dose-dependent—more peanuts, greater benefit—up to a meaningful threshold.

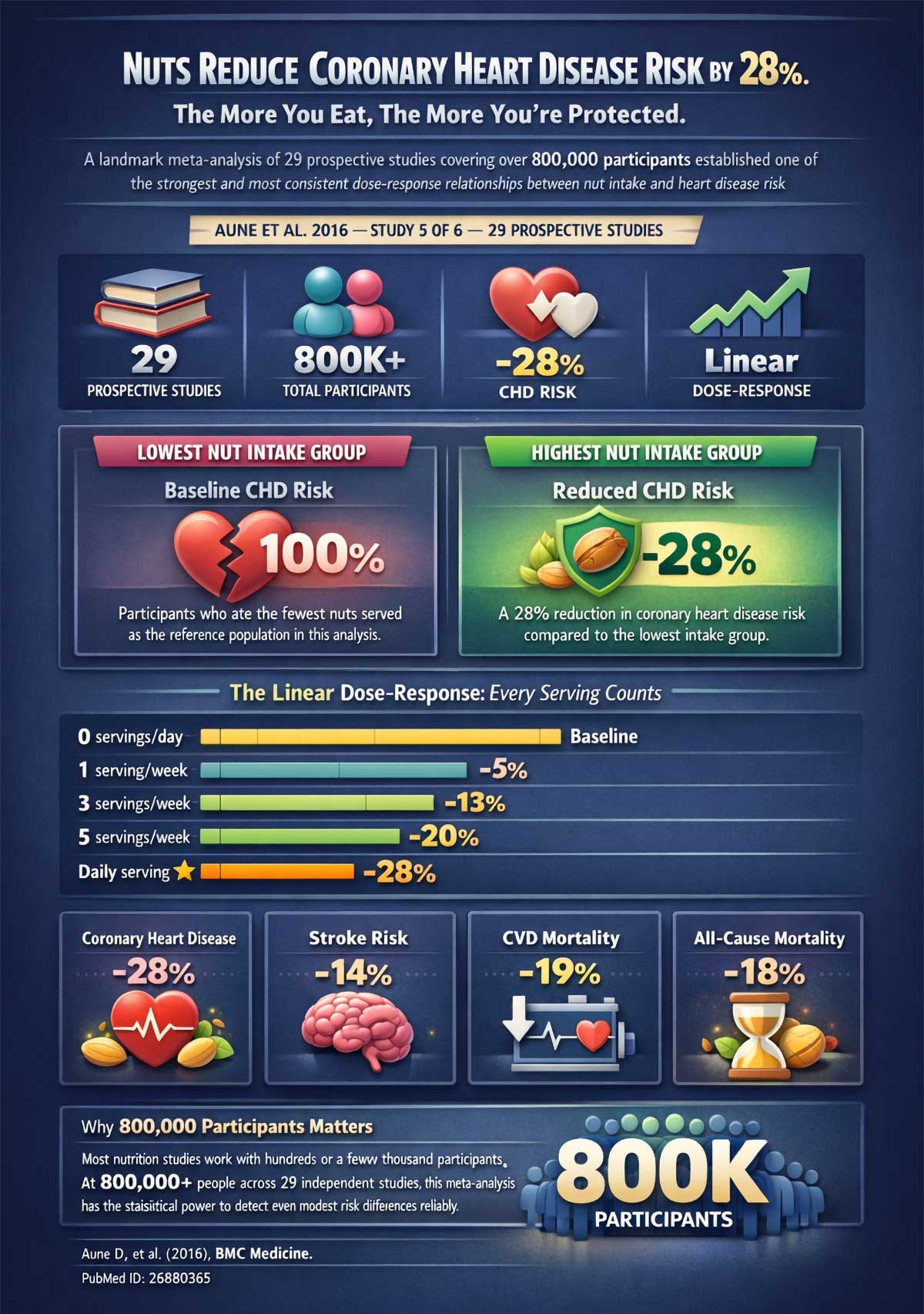

A 2016 meta-analysis by Aune and colleagues added even broader context. Pulling data from 29 prospective studies with over 800,000 participants, the researchers found that people with the highest nut intake had a 28% lower risk of coronary heart disease compared to those eating the least. The relationship was linear: every incremental increase in nut intake corresponded to a measurable reduction in risk.

Taken together, the evidence isn’t just consistent—it’s one of the most well-supported dietary relationships in cardiovascular research.

How You Eat Them Matters

Not all peanuts deliver the same benefit. The form and preparation make a real difference.

The Case for Boiled Peanuts

Boiled peanuts have a distinct nutritional advantage over their roasted counterparts. Boiling increases the concentration of isoflavones—a class of antioxidants linked to reduced inflammation and improved vascular health. Research indicates boiled peanuts consistently outperform roasted varieties in total antioxidant content—in some analyses, significantly so, depending on the specific antioxidant measured.

Boiled peanuts aren’t as widely available as roasted varieties. They’re primarily found in the Southern United States, either fresh or canned. But if you can find them, they’re worth trying.

This doesn’t make raw or roasted peanuts a bad choice. The evidence for those is solid too.

Reading the Peanut Butter Label

Peanut butter can be a genuine heart-health food—or it can be a processed product that works against you. The difference is on the label.

A heart-healthy peanut butter has one or two ingredients: peanuts and possibly a small amount of salt. That’s all.

Problematic varieties contain hydrogenated oils (added to prevent separation), added sugars, and corn syrup. These additions shift the nutritional profile in the wrong direction. Added sugars raise triglycerides. Partially hydrogenated oils contain trans fats, which directly raise LDL.

The rule is simple: if the label lists anything beyond peanuts and salt, put it back.

Check every ingredient on your label below. The tool scores your peanut butter in real time and explains exactly what each ingredient does to your cardiovascular health.

Keep the Skin On

The thin red skin around a peanut is easy to ignore. It’s worth keeping.

That skin is loaded with polyphenols—plant-based antioxidants that reduce oxidative stress in blood vessels. Oxidative stress is one of the driving forces behind arterial plaque buildup. Blanched peanuts (with the skin removed) lose a meaningful portion of this protective compound. Skin-on is the smarter choice for heart health.

Who Should Skip This Advice

For most people, peanuts are remarkably safe and beneficial. But there are clear exceptions.

Anyone with a peanut allergy obviously can’t follow this guidance. If you’re on blood thinners like warfarin, talk to your doctor first—peanuts contain vitamin K, which can interact with these medications. And if you have severe kidney disease, your protein and potassium intake may need monitoring.

For everyone else, the evidence strongly supports making peanuts a regular part of your diet.

Your 3-Week Starting Point

The evidence points to a clear and simple action: one ounce of peanuts per day. That’s roughly a small handful—about 28 grams.

That amount, eaten consistently over three weeks, produced the 14% LDL drop in O’Byrne’s study. It’s also the dose that the large meta-analysis by Liu and colleagues identified as the threshold for meaningful cardiovascular risk reduction.

You don’t need to overhaul your diet. You don’t need supplements. You just need to swap out whatever you’re currently snacking on—crackers, chips, cookies—and replace it with a handful of skin-on peanuts.

A few practical ways to get there:

- Add peanuts to a morning smoothie or yogurt bowl.

- Swap your afternoon vending machine run for a small bag of unsalted, skin-on peanuts.

- Use two tablespoons of natural peanut butter on whole grain toast or apple slices.

- Toss peanuts into a stir-fry or grain bowl for crunch and protein.

The goal for the first three weeks is simply consistency. One ounce, every day. After that, your next cholesterol check will do the talking.

Conclusion

Peanuts aren’t a superfood in the trendy sense. They’re not glamorous. They don’t cost much.

But the evidence behind them is genuinely strong. A 14% LDL reduction in three weeks. A 20% drop in long-term cardiovascular mortality in a study that followed over 100,000 people for three decades. A 13% reduction in CVD risk per ounce consumed daily. Benefits that show up in your cholesterol panel, in the flexibility of your arteries, and in the research records of some of the longest-running nutrition studies ever conducted.

All from a handful of peanuts.

For most people, that’s one of the easiest, cheapest, and most evidence-backed steps they can take for their heart.