A growing body of neuroscience research shows that gratitude isn’t just a warm feeling — it’s a biological process that actively changes how your brain processes experience. And the science is a lot more specific than you might expect.

We’re not talking about forcing a smile or repeating affirmations. Researchers have spent the last two decades studying what happens inside the brain and body when people practice gratitude in structured ways. What they’ve found is striking: real, measurable changes in brain activity, hormone levels, and even markers of physical inflammation.

A large-scale review of 64 randomized controlled trials — covering nearly 7,000 participants — found that gratitude-based practices reduced symptoms of depression by a meaningful margin and lowered anxiety as well. Well-being scores improved. Life satisfaction went up. And critically, these gains held at follow-up checkpoints weeks later (Diniz et al., 2023).

So what’s actually happening under the hood? And more importantly, which practices produce the best results? (If you’re in the middle of a stressful period right now and wondering whether gratitude is even realistic for you, skip ahead to the “Gratitude Under Pressure” section — the answer may surprise you.)

The Brain Science: What Gratitude Actually Does

Most articles stop at “gratitude is good for your mental health.” That’s true, but it’s the how that makes this topic genuinely fascinating.

When you feel and express gratitude, your brain doesn’t just feel good in a vague sense. It activates a specific set of regions tied to reward, moral reasoning, and social connection. A neuroimaging study by Fox et al. (2015) placed 23 healthy adults inside an fMRI scanner while prompting gratitude responses. The results showed increased activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and the anterior cingulate cortex — two regions closely tied to value judgment, moral cognition, and social-emotional processing.

Think of the vmPFC as the brain’s “worth-it calculator.” It helps you assign meaning and value to experiences. When gratitude activates this region, your brain is effectively shifting from threat-scanning mode — the default for stressed, anxious minds — into value-processing mode.

That’s not a small shift. It changes how you interpret what’s happening around you.

What’s even more remarkable is what gratitude does to the body’s stress response. A 2021 study by Hazlett and colleagues took this question further than any prior research. Forty-seven healthy women completed a six-week online gratitude writing program. At the end, researchers measured their inflammatory biomarkers — specifically TNF-α, a pro-inflammatory protein closely tied to stress-related illness. The gratitude group showed a measurable drop in TNF-α compared to the control group. They also showed altered neural responses in the vmPFC during a gratitude task, and an increase in prosocial behavior — being more willing to support others.

In plain terms: consistent gratitude practice may help calm the body’s inflammatory stress response at a biological level. That’s a very different claim than “it makes you feel better.”

Practice 1: The 10-Week Deep Journal — The Foundation

What to do: Once a week, write down five things you’re genuinely grateful for. Don’t rush it. The contrast matters — researchers used a “hassles” comparison group to show what happens when you consistently focus on positives rather than frustrations.

Why it works: In a landmark series of experiments, Emmons and McCullough (2003) tracked 192 undergraduates and 65 adults with neuromuscular disease across three separate studies. The group that journaled weekly about gratitude — compared to those who listed daily hassles or neutral events — showed consistent increases in positive affect, optimism, and overall life satisfaction. That’s the baseline finding.

But what stood out in the chronic illness sample was even more compelling. Those participants slept better, exercised more, and reported greater life satisfaction than the control group — despite living with a long-term health condition. Gratitude, practiced weekly over ten weeks, produced real behavioral and quality-of-life changes in people dealing with genuine hardship.

The key insight: this isn’t about toxic positivity or pretending life is perfect. It’s about training your brain to notice value that your threat-scanning instincts cause you to overlook.

Your starting point: Set a recurring weekly reminder. Sit down for ten minutes with a notebook or a notes app. Write five specific things — not general ones. “My health” is vague. “The fact that I woke up without back pain today” is specific. Specificity is what triggers the neural response.

Practice 2: The Gratitude Letter — The Social Catalyst

Most gratitude practices are private. This one isn’t. And that difference turns out to matter a great deal.

What to do: Write a detailed letter of thanks to someone who’s had a meaningful positive impact on your life — someone you’ve never properly thanked. Then deliver it. Read it to them in person if possible. This is sometimes called a “gratitude visit.”

Why it works: A 2023 meta-analysis by Kirca and colleagues analyzed 34 studies covering over 3,600 participants and reached a clear conclusion: expressed gratitude — the kind you actively communicate to others — produces a medium-to-large effect on well-being (g = 0.47). That’s notably stronger than the effects of quiet, private reflection alone.

The difference is in the social-emotional networks the practice activates. When you write and then deliver a gratitude letter, you’re not just processing a positive memory. You’re engaging your brain’s theory-of-mind systems, your reward networks, and your attachment circuitry all at once. You’re thinking about how another person made you feel, imagining their reaction, and then actually receiving it.

Crucially, the meta-analysis found that delivering the letter outperformed simply writing it. The relational act — the moment of genuine human connection — appears to be where much of the benefit lives.

Your starting point: Pick one person. It doesn’t have to be someone from your distant past. It could be a parent, a teacher, a friend, or a colleague. Write two or three paragraphs about what they did and how it specifically affected your life. Then find a way to share it — in person, by phone, or over video call. Don’t just email it. The live exchange appears to be part of what makes it work.

Practice 3: The Work-Focused Gratitude Practice — The Burnout Buffer

Stress and burnout are not just personal struggles. For many people — especially those in high-pressure jobs like healthcare — they’re occupational hazards. This practice was designed specifically for that context.

What to do: Once a week for four weeks, write about three things related to your work that you’re grateful for. Even when the week has been hard. Especially when the week has been hard. “Three good things” is one common way to structure this — but the core requirement is simply a regular, work-focused written reflection on what you value, however you frame it.

Why it works: A 2021 systematic review by Komase and colleagues pulled together 11 workplace studies covering 1,742 employees across a range of occupations. The conclusion was clear: gratitude-based programs significantly improved psychological well-being and reduced depressive symptoms in work settings. The evidence quality was rated moderate — strong enough to support practical use.

The mechanism behind this involves what researchers call resilience mediation. A clinical trial by Cheng et al. (2015) enrolled 102 healthcare workers experiencing high occupational stress. Half completed a four-week gratitude writing intervention focused on work-related benefits. The other half did an active control task. At the end of four weeks, the gratitude group showed significantly lower perceived stress and fewer depressive symptoms. The improvement was explained, at least in part, by increased resilience — the practice appeared to build a psychological buffer that softened the impact of new stressors.

Think of it like a shock absorber. You’re still hitting the same bumps. But they don’t rattle you quite as hard.

Your starting point: You don’t need a journal for this one. A simple weekly note on your phone works fine. At the end of each workweek, write three sentences starting with: “This week at work, I’m grateful for…” Don’t overthink it. Even small things count — a colleague who covered for you, a meeting that ended on time, a moment of genuine progress on a project.

Practice 4: Gratitude for Young People — The Developmental Advantage

The earlier gratitude habits form, the better. Adolescence is a period of high neurological flexibility — the brain is actively wiring itself based on repeated patterns of thought and behavior. That makes it an ideal time to build a gratitude practice.

What to do: Daily journaling for two weeks. Adolescents list up to five things they’re grateful for each day — specific, personal, and real.

Why it works: A rigorous randomized controlled trial by Froh et al. (2008) enrolled 221 early adolescents between ages 11 and 13 across five classrooms. One group journaled gratitude daily. Another group listed daily hassles. A third group had no intervention. At the end of two weeks — and again at a three-week follow-up — the gratitude group showed higher levels of gratitude, more positive affect, and greater optimism.

The most important finding was about who benefited most. The strongest gains appeared in students who started the study with the lowest levels of positive affect. In other words, the practice was most powerful for the kids who needed it most. Those with naturally low baseline positivity saw the most significant, lasting gains.

This points to gratitude as something that can genuinely shift a young person’s emotional baseline — not just improve their mood in the short term.

Your starting point (for parents and educators): Introduce this as a simple two-week experiment. Avoid framing it as therapy or emotional work — frame it as a journaling habit or a writing challenge. At ages 11–13, buy-in is everything. Make it low-pressure, private, and consistent. Two weeks of daily entries is achievable for most kids, and the evidence suggests even that short window can produce changes that last. That said, sustaining the habit — even just once a week after the initial two weeks — may help those gains stick over the longer term.

Practice 5: The Online Multicomponent Program — Gratitude in the Digital Era

Not everyone has the time or inclination for journaling. Some people do better with structured programs that combine several different approaches at once. That’s where multicomponent interventions come in.

What to do: Over six weeks, engage in a rotating set of gratitude activities online: written reflections, savoring positive moments as they happen, and actively expressing thanks to others in behavioral ways. The key is variety — combining multiple forms of gratitude engagement rather than repeating a single method.

Why it works: A well-designed randomized controlled trial by Bohlmeijer et al. (2021) tracked 217 adults through exactly this kind of six-week online program. Compared to a waitlist control group, participants showed significant improvements in mental well-being — with an effect size of d = 0.46 at the post-test, which is a meaningful result for a psychological intervention.

What made this study particularly valuable was its mediation analysis. Researchers found that increases in gratitude as a mood state — not just a behavior — were the mechanism driving well-being improvements. In other words, the program didn’t just teach people to act grateful. It changed how they habitually felt. And those changes remained stable at a six-month follow-up, long after the program had ended.

This is an important distinction. Gratitude can be cultivated as an ongoing emotional tone, not just a periodic exercise. And it appears that digital programs can achieve this just as well as in-person methods.

Your starting point: Look for structured online programs or apps that combine multiple gratitude modalities — journaling, savoring, and social expression. Avoid apps that only prompt you to list three things daily. The evidence suggests that variety across methods produces more durable change in mood state than any single repeated activity.

Gratitude Under Pressure: What Happens During a Crisis

Here’s something most articles on this topic miss. Gratitude’s benefits are well-documented in stable conditions. But what happens when life genuinely falls apart — during a pandemic, a health crisis, or a period of acute, sustained stress?

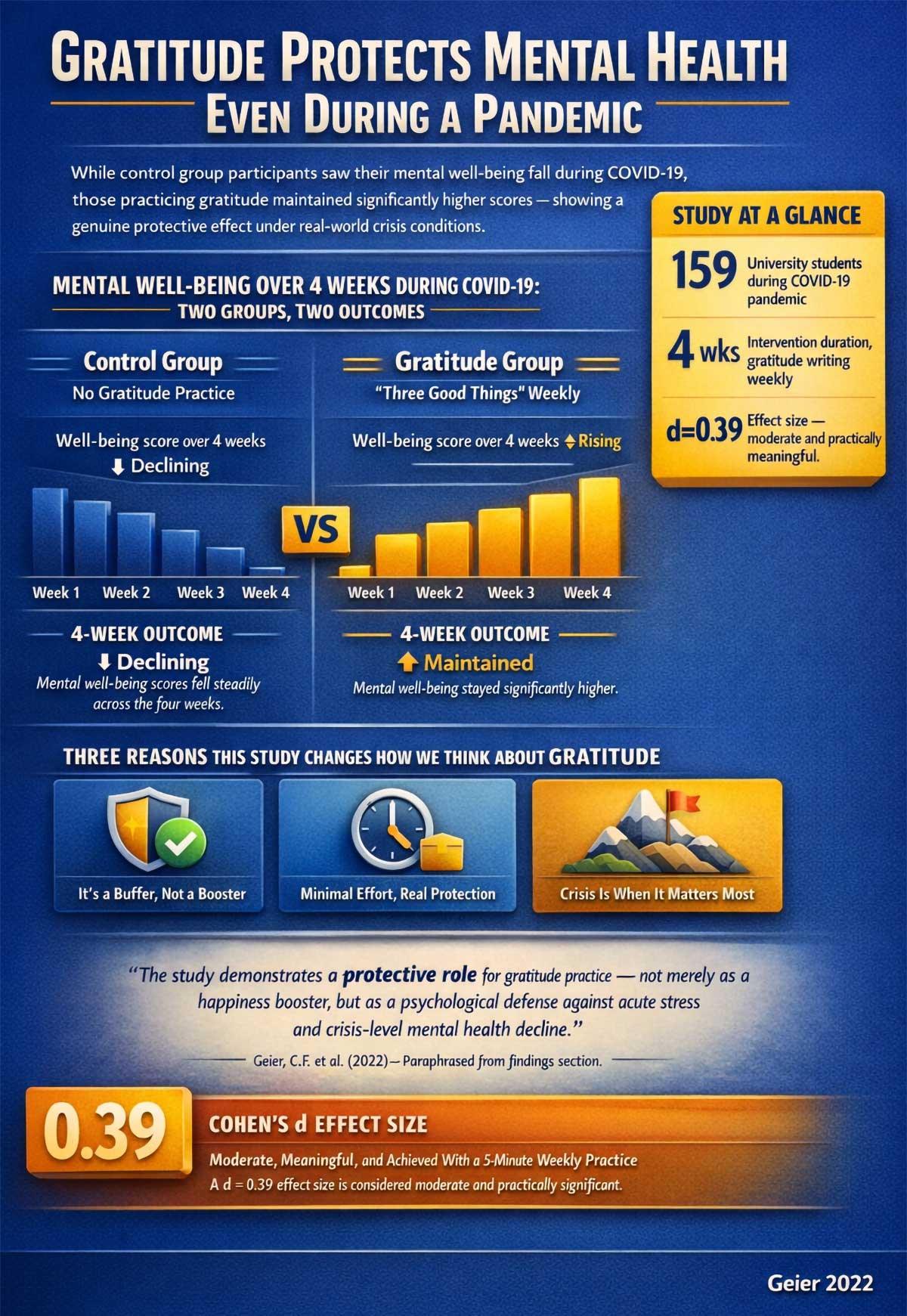

A quasi-experimental study by Geier et al. (2022) addressed this directly. The study enrolled 159 university students during the COVID-19 pandemic and assigned half of them to a four-week “three good things” writing intervention. The other half had no intervention.

By the end of four weeks, the pattern was telling. The control group showed declining mental well-being — exactly what you’d expect during a pandemic. The gratitude group maintained significantly higher well-being throughout. The effect size was d = 0.39: moderate, meaningful, and practically significant given the circumstances.

The key phrase the researchers used was “protective role.” Gratitude, in this context, wasn’t a happiness booster. It was a buffer. It didn’t eliminate the stress. It kept mental health stable while everything else was pulling it downward.

This reframes how to think about gratitude during hard times. Many people assume that practicing gratitude during a crisis is naive — that it dismisses real suffering. The evidence suggests the opposite. The more acute the stress, the more valuable the buffer may be.

It’s also worth knowing what the research says works less well. Private journaling and emailing a gratitude letter both produce benefits — but they’re notably weaker than practices that involve live human connection or direct behavioral expression. Writing a gratitude letter and keeping it in a drawer is useful. Writing it and reading it aloud to the person it’s meant for is significantly more so. Similarly, a vague journal entry (“I’m grateful for my family”) produces less benefit than a specific one (“I’m grateful that my sister called to check on me after a rough week”). The research is consistent on both points: social expression beats private reflection, and specificity beats generality. That’s worth keeping in mind when you’re choosing how to start.

Your 30-Day Starting Point: Pick One and Begin

You don’t need to adopt all five practices at once. In fact, that would likely be counterproductive. The evidence consistently shows that consistency matters more than volume.

Here’s how to choose:

If you’re dealing with work stress or burnout, start with Practice 3 — the work-focused gratitude practice. It’s low-effort, work-specific, and backed by direct research in exactly your context.

If you have an important relationship you’ve never fully acknowledged, start with Practice 2 — the gratitude letter. It’s a one-time act with documented medium-to-large effects on well-being that last for months.

If you’re looking for a foundational, long-term habit, Practice 1 — the ten-week deep journal — is the most well-studied starting point. Set a weekly time and protect it.

If you’re supporting a young person, Practice 4 is worth two weeks of low-pressure daily effort. The developmental window of adolescence makes this a high-return investment.

If you prefer variety and structure, Practice 5 — the multicomponent online program — delivers lasting mood-state changes across a six-week arc.

Conclusion

Here’s what the neuroscience ultimately tells us: gratitude is less a personality trait and more a trainable skill. Every time you deliberately activate the vmPFC through a structured gratitude practice, you’re reinforcing the neural pathways that make value-processing — rather than threat-scanning — your brain’s default mode. Over time, that shift becomes more automatic.

The brain responds to what you repeat. Repeat gratitude, and your brain begins to expect it. That expectation is what researchers call “resilience.” And it’s not something you’re born with or without. It’s something you build.