Fear of failure isn’t a weakness. It’s not a sign you lack drive or talent. Your brain is doing what it thinks is right—trying to protect you. But here’s the problem: this “safety mode” often backfires.

Let’s explain how your mind works against you. Then we’ll show you research-backed ways to flip the script.

A note on the research: Studies on performance anxiety, test anxiety, and fear of failure show significant overlap in their underlying mechanisms. The cognitive reframing strategies discussed here have been tested across these related anxiety types. While not every study specifically measured “fear of failure,” they all address the same core issue: how we interpret and respond to performance pressure.

The Hidden Cost of “Safety First”

Your brain has one job above all others: keep you safe. When you face a challenge—a test, a job interview, a tough conversation—your mind scans for danger. It asks: “Can this hurt me?”

The answer is usually yes. Not physical harm, but something your brain treats as just as serious: damage to your sense of self.

This is where things go sideways. Your brain doesn’t see the difference between a tiger and a failed project. Both trigger the same alarm system. Both make your body prepare for a threat.

Scientists call this a “threat appraisal.” Your mind decides you don’t have the tools to handle what’s coming. So it activates your stress response. Heart rate spikes. Breathing gets shallow. Focus narrows.

Here’s the twist: trying not to fail makes you more likely to mess up. When you focus on avoiding mistakes, you create what athletes call a “choke response.” Your performance drops. Your anxiety climbs. You prove your fears right.

This isn’t your fault. It’s biology. But you can change it.

This assessment helps identify your relationship with failure and performance anxiety. Answer honestly for the most accurate results. There are 12 questions, and it takes about 3 minutes.

Understanding the Mechanics: Why Failure Feels Like a Physical Threat

Your fear of failure starts with how you process information. Research shows that when you’re anxious, your brain looks for proof that things will go wrong. You notice every small mistake. You ignore what goes right.

This is called biased cognitive processing. Your mind filters reality through a lens of threat. A neutral comment from your boss becomes criticism. A small error becomes proof you’re not good enough.

Psychologists Aaron Beck and David Clark studied this pattern for decades. Their work showed that people with anxiety disorders process threats differently than others. They see danger where none exists. They blow small risks out of proportion. Their cognitive therapy approach targets these exact distortions, helping people see situations more clearly.

The Appraisal Loop Explained

The cycle works like this:

You face a situation. Your brain appraises it as a threat or a challenge. If it’s a threat, you think: “I can’t handle this.” If it’s a challenge, you think: “I can do this.”

That split-second decision changes everything. Researchers Richard Lazarus and Susan Folkman spent years studying this process. They found that stress doesn’t come from events themselves. It comes from how you appraise those events. Your mind asks two questions: Is this dangerous? Do I have what it takes to cope?

If you answer “yes” to danger and “no” to coping, stress skyrockets.

Threat vs. Challenge: What’s the Difference?

The difference between threat and challenge comes down to resources. Do you believe you have what it takes to cope? If yes, your body responds with energy and focus. If no, your body responds with panic and shutdown.

| Your Brain Sees a THREAT When: | Your Brain Sees a CHALLENGE When: |

|---|---|

| You focus on what could go wrong | You focus on what you could gain |

| You believe you lack the skills | You believe you can learn the skills |

| Stakes feel permanent (“This defines me”) | Stakes feel temporary (“This is one test”) |

| You imagine harsh judgment | You expect useful feedback |

| Past failures feel like proof | Past failures feel like practice |

Most people with fear of failure get stuck in threat mode. They see every test as proof of their worth. Every mistake as a sign they’re not cut out for success.

A major analysis by Stefan Hofmann and colleagues looked at 106 studies on cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety. They found that CBT produced large improvements in reducing anxiety symptoms. The effect held up across different types of anxiety and stayed strong even months after treatment ended. The key? Teaching people to catch and change these threat-based thought patterns.

But your racing heart and sweaty palms? They’re not signs of weakness. They’re your body preparing for action. The question is: can you change how you see them?

What Exactly Are You Afraid Of?

Before we talk about solutions, let’s get specific about your fear. Vague dread is harder to tackle than concrete worries.

Grab a piece of paper. Write down what you’re actually scared will happen. Be specific.

Not: “I’m afraid of failing this test.” But: “I’m afraid I’ll get a C, my parents will be disappointed, and I’ll feel like I wasted their money.”

Now ask yourself three questions:

- What’s the worst that could realistically happen?

- What’s the best that could happen?

- What’s most likely to happen?

This exercise stops vague dread and starts problem-solving. When you name your fear, it loses some of its power. You can plan for it. You can challenge it. You can see it clearly instead of through a fog of anxiety.

Most people find their worst-case scenario isn’t actually that bad. Or if it is bad, they realize they could survive it. You’re stronger than your fear gives you credit for.

Strategy #1: Reframe Arousal as Your Competitive Edge

Stop trying to calm down. I know that sounds strange. But research shows something surprising: telling yourself to relax before a stressful event doesn’t work very well.

What does work? Changing what your stress symptoms mean.

The Science Behind Arousal Reappraisal

When your heart pounds and your breathing quickens, most people think: “I’m freaking out. This is bad. I need to stop this.” This makes anxiety worse. You’re now anxious about being anxious.

Try this instead: “My body is getting me ready. My heart is pumping more blood to my brain. I’m becoming sharper and faster.”

This is called arousal reappraisal. You’re not changing the feeling. You’re changing what it means.

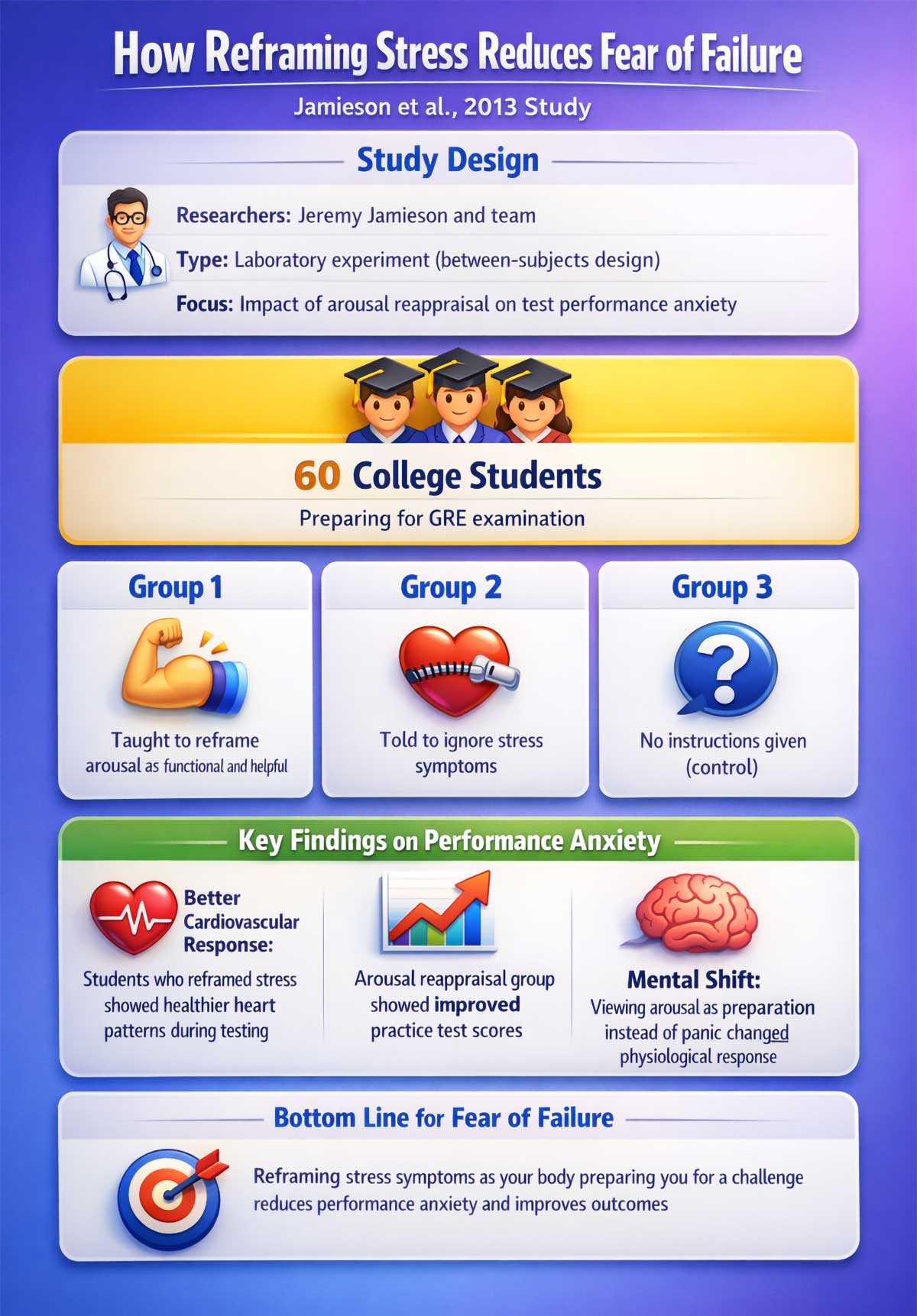

Psychologist Jeremy Jamieson tested this with 60 college students preparing for the GRE. He taught one group to view their stress as helpful—explaining that arousal improves focus and performance. Another group learned to ignore their stress. A third group got no instructions.

The result? Students who reframed their stress showed healthier heart patterns during the test. Their bodies responded to the challenge instead of to a threat. They also performed marginally better on practice tests.

How to Practice Stress Reframing

Think of stress like a race car engine. High RPMs aren’t a problem if you’re on the track. They’re exactly what you need. Your stress response is the same. It’s not breaking you down. It’s revving you up.

Here’s how to use this:

Before a stressful event, notice your body’s signals. Racing heart? Tight chest? Fast breathing? Label them out loud: “I feel my heart beating fast.”

Now relabel them: “My heart is sending extra oxygen to help me think clearly. My body is preparing me to perform.”

The physical feeling won’t disappear. But your relationship to it changes. You stop fighting your own biology. You start working with it.

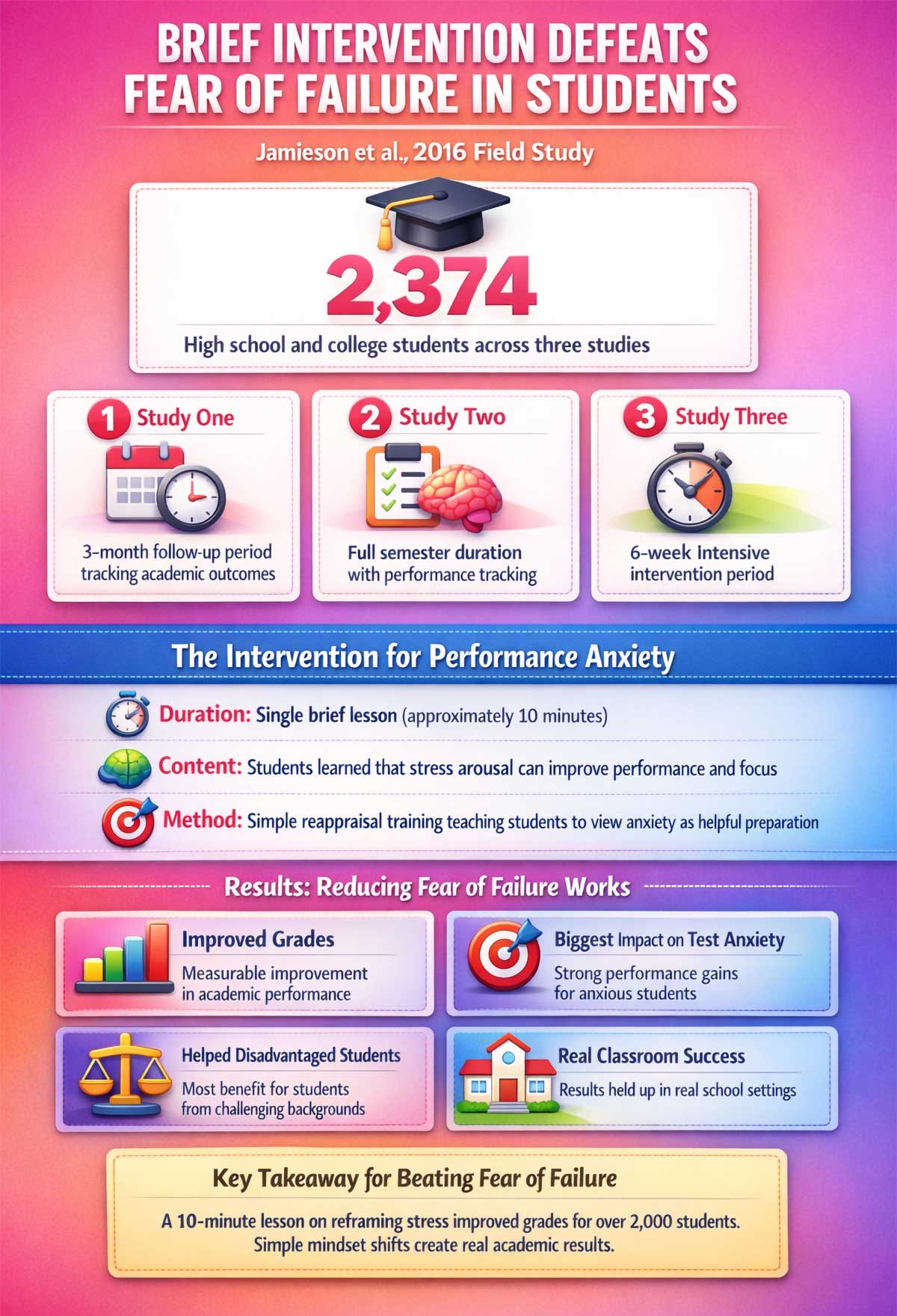

Jamieson didn’t stop with one study. He and his team ran three more trials with over 2,000 high school and college students. They taught students brief lessons—ranging from single reading exercises to short classroom sessions—about how stress can help performance.

Students who learned this strategy showed improved academic performance. The intervention changed how students appraised stress (the mechanism), which led to better cardiovascular responses (physiological outcome) and higher grades (behavioral outcome). The effect was strongest for students with test anxiety and those from tough backgrounds.

Key Insight: Your brain treats failure as a threat to survival. That’s biology, not weakness.

How it works: Choose a stressful scenario, then see how your body and performance differ based on whether you view the situation as a threat or a challenge.

This simulation is based on research showing that reframing arousal changes your physiological response.

Big Presentation

Important Test

Job Interview

Athletic Competition

Your heart is racing. How do you interpret this?

"I'm panicking. This is bad. I need to calm down or I'll mess up."

"My body is getting me ready. This energy will help me perform."

Strategy #2: From Perfectionism to “Functional Failure”

Perfectionism and fear of failure are close friends. If you believe anything less than perfect is failure, you’ll see threats everywhere.

This type of thinking is called “all-or-nothing.” You win or you lose. You succeed or you fail. No middle ground exists.

Cognitive behavioral therapy targets this exact pattern. The approach is simple but powerful: catch the thought, check the facts, and replace it with something more accurate.

Common Thinking Errors and How to Fix Them

Let’s say you think: “If I don’t get this promotion, I’m a total failure.” Stop. Check that thought. Is it really true?

Did LeBron James become a failure when he lost his first NBA finals? Did Thomas Edison quit after his first thousand failed light bulbs? Failure is data. Nothing more.

| Thinking Error | Example | Reality Check | Reframe |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-or-Nothing | “If I don’t get an A, I’m stupid” | Most outcomes aren’t binary | “A B means I learned 85% of the material” |

| Catastrophizing | “One mistake will ruin everything” | Single errors rarely cause total failure | “I can recover from this” |

| Mind Reading | “They think I’m incompetent” | You can’t know others’ thoughts | “I don’t have evidence for this” |

| Overgeneralizing | “I always mess up presentations” | “Always” is rarely accurate | “I’ve had tough presentations and good ones” |

| Discounting Positives | “That success was just luck” | Success often involves skill and effort | “I prepared well and it paid off” |

Learn to spot common thinking errors that fuel fear of failure. Read each scenario and identify which cognitive distortion is present. You'll get immediate feedback and see the healthy reframe.

Scenario 1 of 10

The Data-Driven Mindset

The goal isn’t to stop caring about results. The goal is to shift your focus from outcome to process.

Ask yourself: “Did I prepare well? Did I use good technique? Did I give my best effort?” These are the things you control. The final result? Often that’s out of your hands.

Research on cognitive restructuring shows this shift reduces anxiety. When you stop measuring yourself only by wins and losses, the pressure drops. You can breathe. You can think. You can perform.

Athletes use this approach all the time. They don’t focus on the scoreboard during the game. They focus on executing each play. One pass. One shot. One step at a time.

You can do the same. Break your big scary goal into small actions. Judge yourself on those actions, not on outcomes you can’t fully control.

Build Your Success Case File

Your brain remembers failures vividly. It forgets wins easily. Fix this imbalance.

For one week, write down three things each day:

- One thing you did well (any size)

- One mistake you made and what you learned

- One skill you’re building

This trains your brain to see progress, not just problems. After a week, look back at your entries. You’ll see patterns. You’ll notice growth. You’ll have proof that you’re not stuck—you’re moving forward.

Keep this log going. On hard days, read it. Your past successes are evidence against your fear’s lies.

Strategy #3: The Self-Compassion Buffer

When you mess up, what do you say to yourself?

If you’re like most people with fear of failure, you’re brutal. “I’m so stupid. I always screw up. I’m never going to get this right.”

You think this harsh voice will motivate you. It doesn’t. It makes things worse.

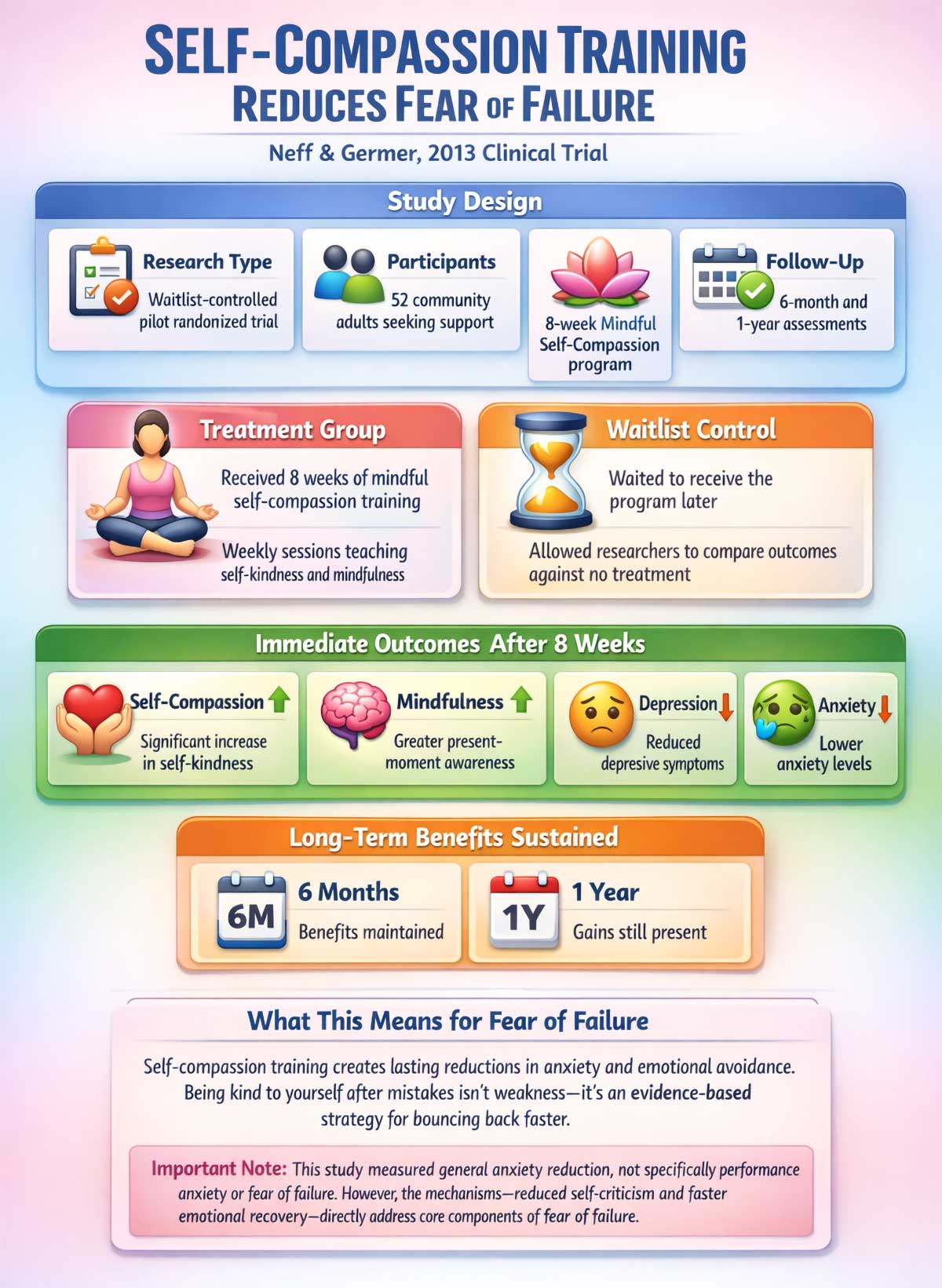

Researchers Kristin Neff and Christopher Germer ran a study with 52 adults. They taught half the group an 8-week program on mindful self-compassion. The other half waited to start the program later.

The results were clear. People who learned self-compassion showed less anxiety and depression. They worried less. They felt more connected to others. These gains didn’t just last during the program—they held up six months later, even a year later.

Important note: This study measured general anxiety reduction, not specifically performance anxiety or fear of failure. However, the mechanisms—reduced self-criticism and faster emotional recovery—directly address core components of how people respond to failure.

Beyond Softness: Why Self-Compassion Works

Self-compassion isn’t about making excuses. It’s about treating yourself like you’d treat a good friend who failed.

Would you tell your friend they’re worthless after a mistake? No. You’d say: “That was tough. You tried hard. What can you learn from this?”

Give yourself the same grace.

Think of self-compassion as a shock absorber. When you hit a bump—a failed test, a rejected proposal, a missed opportunity—self-compassion softens the blow. You don’t spiral into shame. You don’t freeze up. You assess what happened and move forward.

The research backs this up. People who practice self-kindness show more resilience. They try harder tasks. They persist longer. They see failure as part of learning, not as proof of their inadequacy.

Being kind to yourself isn’t soft. It’s smart. It keeps you in the game.

Remember: Self-compassion isn’t soft. It’s strategic.

How to Practice Self-Compassion

Next time you mess up, try this three-step process:

- Notice your pain. Say to yourself: “This hurts. I’m disappointed.”

- Remember you’re human. Say: “Everyone makes mistakes. I’m not alone in this.”

- Be kind. Say: “What do I need right now? What would I tell a friend?”

It feels weird at first. You might feel like you’re letting yourself off the hook. You’re not. You’re giving yourself the support you need to try again.

Strategy #4: Mental Toughness and the Growth Mindset

Elite performers may still experience fear of failure, but research suggests they process it differently—viewing challenges through a lens of controllability and growth rather than threat.

They see failure as feedback. Not a judgment on their worth. Not a sign they should quit. Just information about what needs to change.

This is called a growth mindset. The belief that skills develop through effort and learning. Mistakes aren’t dead ends. They’re part of the path.

Note on this strategy: While the controllability focus comes from well-established stress theory (Lazarus & Folkman), applying it specifically to fear of failure draws on both correlational research and theoretical frameworks rather than direct intervention studies.

The Performance-Fear Connection

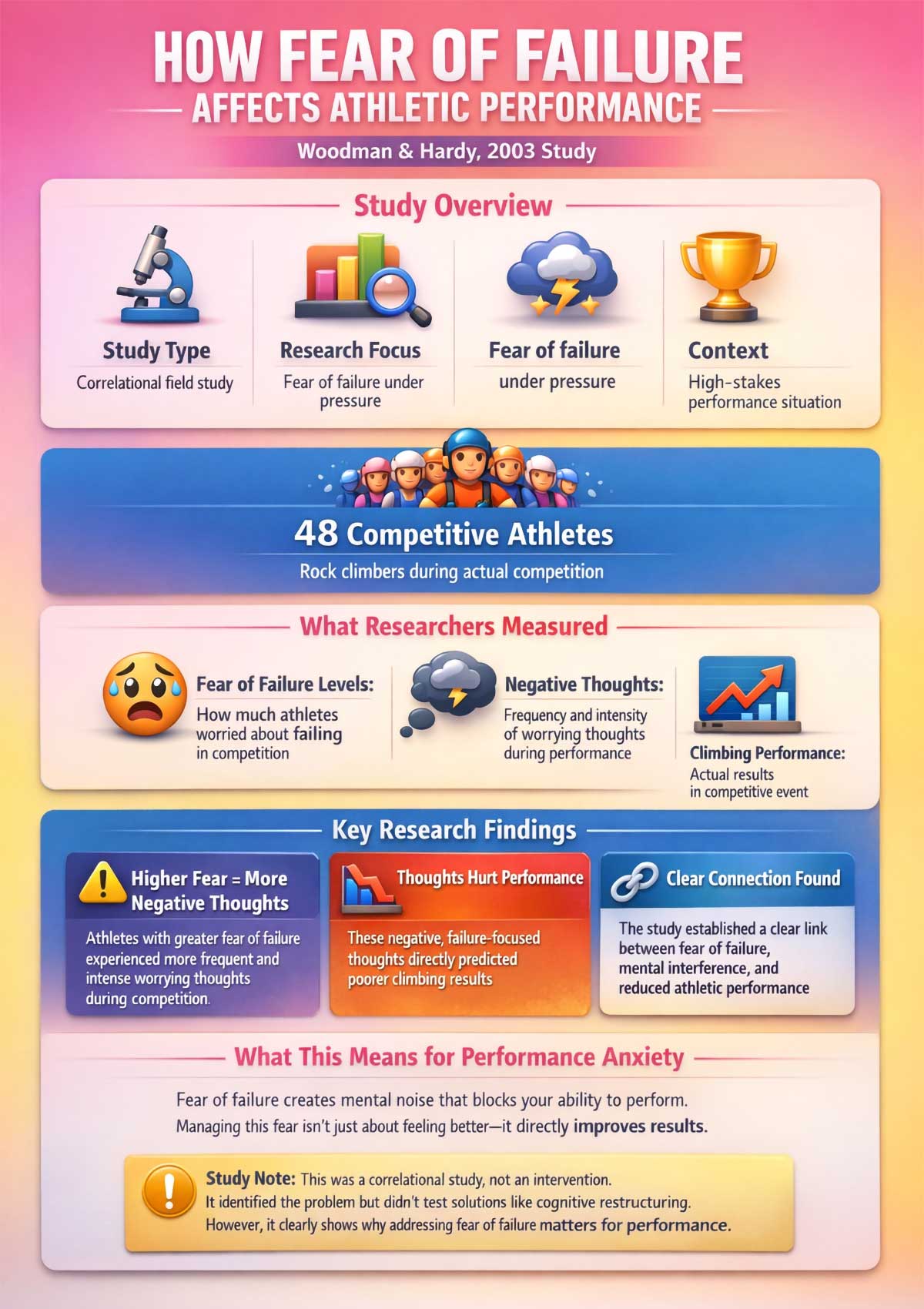

Research with competitive athletes shows this pattern clearly. Sport psychologists Tim Woodman and Lew Hardy studied 48 rock climbers during competition. They found that climbers with higher fear of failure experienced more frequent and intense negative thoughts while climbing. These worried thoughts predicted poorer performance.

The athletes weren’t less skilled. Their fear created mental noise that blocked their ability to execute what they already knew how to do. While this study didn’t test an intervention, it clearly shows why managing fear of failure matters for performance.

Controllability: Focus on What You Can Change

The difference wasn’t talent. It was perspective.

Here’s what mental toughness looks like in practice: focus on what you can control. You can’t control the judge’s opinion. You can’t control if your competitor has a great day. You can’t control unexpected problems.

But you can control your effort. Your preparation. Your attitude. Your willingness to learn.

When you focus on controllable factors, fear shrinks. You stop worrying about things outside your power. You put your energy into what matters.

This doesn’t mean you ignore results. It means you don’t let results define you. You’re not your GPA. You’re not your job title. You’re not your last performance.

You’re a person who’s learning. Growing. Trying.

How This Looks in Real Life

These strategies sound good on paper. But how do you actually use them? Let me break it down by situation.

For Students

Before tests: Use arousal reappraisal. When your heart races, tell yourself: “My body is preparing me to think fast and recall information.” Research shows this single shift improved test scores, especially for students with test anxiety.

After bad grades: Apply self-compassion. Instead of “I’m stupid,” try “This grade doesn’t define me. What can I learn for next time?” This keeps you motivated instead of defeated.

During studying: Focus on controllable factors. You can’t control the test questions. You can control how many practice problems you do, how well you sleep, and whether you ask for help.

For Professionals

Before presentations: Reframe nervous energy as excitement. Both feelings create the same physical response. Choosing to call it excitement instead of anxiety changes how you perform.

After mistakes at work: Use cognitive restructuring to avoid catastrophizing. “I sent that email to the wrong person” doesn’t mean “I’m going to get fired and never work again.” Catch the thinking error. Replace it with what’s actually true.

During performance reviews: Separate feedback from identity. Critical feedback means your work needs improvement. It doesn’t mean you’re a bad person or employee.

For Athletes

Pre-competition: Channel arousal into focus. That pumping heart? That’s your body preparing you to move fast and react quickly. Use it.

Post-loss: Practice self-compassion to maintain motivation. The best athletes lose sometimes. What separates them is how fast they bounce back. Beating yourself up slows recovery.

During training: Focus on process goals over outcome goals. “I want to win the championship” is an outcome. “I want to perfect my free throw technique” is a process. You control the process. The outcome follows.

Quick Reference: Four Strategies at a Glance

| Strategy | What It Does | Use It When | Time Needed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arousal Reappraisal | Turns stress symptoms into performance fuel | You feel physical anxiety (racing heart, sweating) | 30 seconds |

| Cognitive Restructuring | Catches and fixes thinking errors | You’re stuck in negative thought loops | 2-5 minutes |

| Self-Compassion | Reduces shame after mistakes | You’re beating yourself up | 1-3 minutes |

| Controllability Focus | Directs energy to what you can change | You feel overwhelmed by uncertainty | 5 minutes |

Pick the strategy that fits your situation. You don’t need to use all four at once. Master one. Then add another.

Interactive Toolkit: The 3-Step Reframing Protocol

Let me give you a simple system you can use right now. I’ve used this with clients. They report it helps cut through anxiety fast.

Step 1: Label the Physical Sensation

When fear hits, name what you feel. Don’t judge it. Just notice it.

“My chest feels tight.” “My hands are shaking.” “My stomach is churning.”

This simple act creates distance. You’re not the feeling. You’re observing the feeling.

Psychologists James Gross and Oliver John studied emotion regulation strategies in 122 adults. They found that people who habitually reappraise their emotions—who change what emotions mean—show better outcomes. They feel more positive emotions. They have better relationships. They cope with stress more effectively.

The people who tried to suppress emotions instead? They felt worse. Suppression backfires. Reappraisal works.

Step 2: Relabel the Meaning

Now assign a new story to that sensation.

Instead of: “My tight chest means I’m panicking.”

Try: “My tight chest means my body is sending extra oxygen to help me focus.”

Instead of: “My shaking hands mean I can’t do this.”

Try: “My shaking hands mean my muscles are getting ready to act.”

You’re telling your brain: this isn’t danger. This is preparation.

Step 3: Take Action

Don’t wait for the feeling to go away. It won’t. And that’s okay.

Commit to one small next step. Send the email. Make the call. Write the first sentence.

Action breaks the freeze response. It shows your brain that the “threat” isn’t actually dangerous. You can handle it.

Do this enough times, and your brain learns a new pattern. Stress becomes a signal to engage, not to run.

Your 60-Second Reset Routine

Create a simple script to use before stressful events. Practice it when stakes are low. It’ll be there when stakes are high.

1. Breathe: Take three deep breaths. Four seconds in. Six seconds out. This activates your calming system.

2. Name it: “I feel nervous. That’s my body getting ready.” Label without judgment.

3. Purpose: “My goal is to [specific action], not to be perfect.” Set a process goal, not an outcome goal.

4. Action: “First step is [one small thing].” Break it down. Start small.

Run through this sequence. It takes one minute. It shifts your brain from threat mode to challenge mode.

When to Seek Professional Help

These strategies help with typical fear of failure. But some signs mean you need professional support.

Talk to a therapist or psychologist if:

- Anxiety prevents you from trying things repeatedly

- You avoid entire areas of life due to fear

- Panic attacks occur regularly

- Sleep problems last for weeks

- You have thoughts of self-harm

- Anxiety existed for months without improvement

- Fear interferes with work, school, or relationships

A therapist can provide tools these articles can’t. Cognitive behavioral therapy has strong research backing for anxiety disorders. The analysis by Hofmann and colleagues showed CBT works well for many types of anxiety, with effects that last long after treatment ends.

There’s no shame in getting help. Actually, seeking therapy is one of the smartest things you can do. It means you’re taking your mental health seriously.

Many therapists now offer online sessions, making help more accessible. If cost is a concern, look for therapists who offer sliding scale fees or check if your insurance covers mental health care.

Research Fact: Students who reframed stress as helpful improved their grades significantly.

The New Definition of Success

The most successful people aren’t the ones who never fail. They’re the ones who fail efficiently.

They fail, learn, adjust, and try again. Fast. Without the long detour through shame and self-doubt.

You can become one of them. Not by getting rid of fear. Not by never making mistakes. But by changing what those things mean.

Your racing heart before a challenge? That’s energy. Your worry about messing up? That’s your brain trying to prepare you. Your past failures? Those are your education.

The research is clear. When you reframe stress as helpful, your body responds better. When you treat failure as data instead of disaster, you learn faster. When you’re kind to yourself, you bounce back stronger.

Your Next Steps

Pick one strategy. Not all four. Just one.

If you struggle with test anxiety, try arousal reappraisal this week. If you beat yourself up after mistakes, practice self-compassion daily. If perfectionism runs your life, work on cognitive restructuring.

Master one tool. Then add another. Small changes compound over time.

Start with the Fear Inventory exercise. Thirty minutes. A piece of paper. Get specific about what you’re actually afraid of. That clarity alone reduces anxiety for many people.

Then move to the 3-Step Reframing Protocol. Use it once this week before something stressful. Notice what happens. Did your performance change? Did your anxiety level shift? Did you recover faster afterward?

Track your progress. Not perfectly—just honestly. The Evidence Log gives you data. After two weeks, you’ll see patterns. You’ll notice what works for your brain.

Thousands of people have changed their relationship with failure using these research-backed methods. You can too. Your fear doesn’t have to shrink for your life to grow. You just need better tools.

Your 30-Day Fear of Failure Action Plan

Change doesn’t happen overnight. But consistent practice creates lasting shifts. Here’s a plan to guide you.

Check off each item as you complete it. Don’t expect perfection. Some days you’ll forget. Some strategies will feel awkward. That’s normal. You’re building new mental habits. It takes time.

FAQs

Is fear of failure a mental illness?

No. Fear of failure is a common experience. It becomes a problem when it stops you from living your life. Clinical anxiety disorders need professional diagnosis. Most people with fear of failure don’t have a disorder. They just need better coping tools.

How long does it take to see results from these strategies?

It varies. Some people notice changes in weeks using these techniques. Others need months. Consistency matters more than speed. The research on arousal reappraisal showed benefits from brief interventions, sometimes as short as a single reading exercise or brief classroom lesson. However, deeper patterns like all-or-nothing thinking take longer to shift. Give yourself at least 30 days of daily practice before judging results.

Can fear of failure ever be helpful?

Yes. Mild concern about outcomes can boost motivation. The problem starts when fear paralyzes you instead of energizing you. A little anxiety sharpens focus. Too much anxiety shuts you down. The goal isn’t to eliminate all fear. It’s to keep fear at a level that helps instead of hurts.

Do I need therapy to get better?

Not always. Many people improve using self-help strategies like the ones in this article. Therapy helps when anxiety is severe, when self-help isn’t working after several months, or when anxiety interferes with daily life. A therapist can personalize strategies to your specific situation and provide support you can’t get from an article.

What’s the difference between fear of failure and perfectionism?

They’re related but not identical. Perfectionism is the belief that anything less than perfect is unacceptable. Fear of failure is the emotional response to that belief. Both respond well to cognitive restructuring. When you change perfectionist thoughts, fear of failure often decreases.

I’ve tried positive thinking before and it didn’t work. How is this different?

These strategies aren’t about forced positivity. You’re not telling yourself “everything will be fine” when you don’t believe it. You’re examining the actual evidence, catching thinking errors, and reframing arousal based on science. Research shows these cognitive approaches work better than generic positive thinking because they’re grounded in reality, not wishful thinking.

Can these strategies help with imposter syndrome?

Absolutely. Imposter syndrome involves many of the same thinking errors—discounting your successes, catastrophizing mistakes, and all-or-nothing thinking. The Evidence Log is especially helpful for imposter syndrome because it creates objective proof of your accomplishments that your brain can’t dismiss as easily.

Medical Disclaimer: This article provides educational information about fear of failure and performance anxiety. It’s not a substitute for professional mental health care. If anxiety interferes with your daily life, talk to a licensed therapist or psychologist.