Eggs are confusing. One year they’re heart attack fuel. The next, they’re a superfood. Doctors debate them. Headlines contradict each other. And most people just want a straight answer before breakfast.

That straight answer now exists. For most people, eggs aren’t the enemy. But the full picture is more interesting than a simple yes or no. It depends on what’s on the rest of your plate, and even your DNA.

The 32-Year Verdict: What Happened When 215,000 People Ate Eggs Every Day

In 2020, researchers at Harvard published a study that should have ended the egg debate for good. They followed 215,618 nurses and health professionals across three large US cohorts for up to 32 years. That’s not a short-term experiment. That’s decades of real dietary data.

Their finding? Eating up to one egg a day was not linked to heart disease, stroke, or cardiovascular death. Not even close. The researchers—Drouin-Chartier et al.—found no meaningful risk at moderate intake levels, even when they looked at higher consumption.

What made the findings even more useful was the comparison data. People who replaced eggs with processed meats like bacon or sausage had a higher risk of heart disease. Those who swapped eggs for nuts or whole grains showed a modest drop in risk. This places eggs in a neutral-to-positive category—not dangerous, and better than many common alternatives.

Why Your Liver Is Smarter Than You Think

To understand why eggs don’t raise heart risk the way people fear, you need to understand what your liver does every day without you asking.

Your body produces cholesterol on its own. It does this because cholesterol is essential—for hormones, cell membranes, and brain function. When you eat more cholesterol through food, your liver dials back its own production to keep levels balanced. It’s a built-in feedback system.

This is why dietary cholesterol—the cholesterol in food—doesn’t automatically translate into high blood cholesterol. Your body adjusts. For most people, eating an egg doesn’t send their LDL numbers soaring. The system self-corrects.

This understanding is exactly why the 2015 US Dietary Guidelines dropped the decades-old recommendation to limit dietary cholesterol to 300 mg per day. The advisory committee concluded that dietary cholesterol simply isn’t a meaningful risk factor for heart disease in most people. Your liver’s regulatory system matters far more than what’s on your breakfast plate.

The Cholesterol Shift Nobody Talks About

But there’s more to the story than just total numbers.

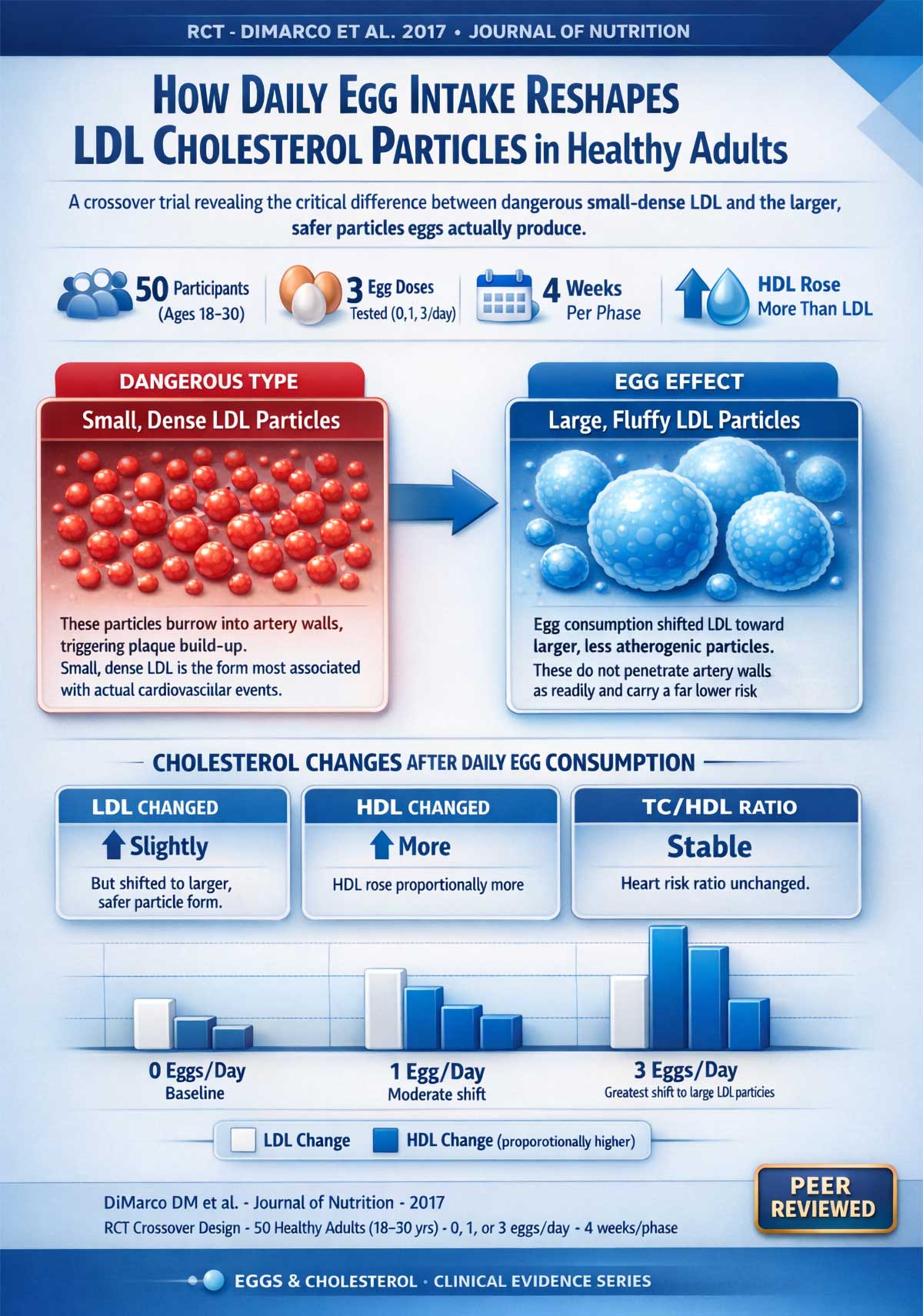

Research shows that eggs don’t simply “raise cholesterol.” They shift it. A well-designed study by DiMarco et al. in 2017 tested what happened when 50 healthy young adults ate zero, one, or three eggs per day. Yes, LDL cholesterol went up with egg intake. But so did HDL—the protective kind. More importantly, the LDL particles themselves changed shape. They became larger and less dense.

This matters because small, dense LDL particles are the ones that burrow into artery walls and cause damage. Large, “fluffy” LDL particles are far less likely to do that. So the egg wasn’t raising dangerous cholesterol. It was shifting the balance toward a safer profile.

The HDL Bonus: Your Cardiovascular Cleanup Crew

HDL cholesterol acts like a cleanup crew. It pulls excess cholesterol out of the bloodstream and brings it back to the liver for removal. Higher HDL is generally linked to lower heart disease risk, though recent research suggests HDL function matters as much as HDL quantity. Still, the consistent HDL increases from egg consumption represent a meaningful shift for most people.

Eggs raise HDL. Multiple studies confirm this. In the DiMarco study, HDL increased proportionally more than LDL did. A 2015 meta-analysis by Berger et al., which analyzed 17 randomized controlled trials involving 1,025 participants, confirmed that egg consumption raised both LDL and HDL—but crucially, the ratio between total cholesterol and HDL stayed stable. That ratio is one of the strongest predictors of heart risk. When it stays flat, your risk profile doesn’t worsen.

This is the nuance that most anti-egg headlines miss entirely.

Why American Eggs Look Dangerous and Chinese Eggs Don’t: The Hidden Variable

Here’s where things get interesting—and a little controversial.

A 2019 study by Zhong et al. caused a wave of alarming headlines. It analyzed data from nearly 30,000 US adults and found that every additional 300 mg of dietary cholesterol per day—roughly one and a half to two eggs—was linked to a 17% higher risk of cardiovascular disease. Three to four eggs per week was linked to a 6% higher risk.

Scary numbers. But the study had a serious problem.

It didn’t adequately account for what people ate with their eggs. In the US, eggs rarely show up alone. They come with bacon, sausage, buttered toast, hash browns, and white biscuits. That’s not an egg problem. That’s a Western breakfast problem. Saturated fat from processed meats, refined carbohydrates from white bread and pastries—these are the factors that damage arteries. The egg was sitting next to the suspects and got blamed for the crime.

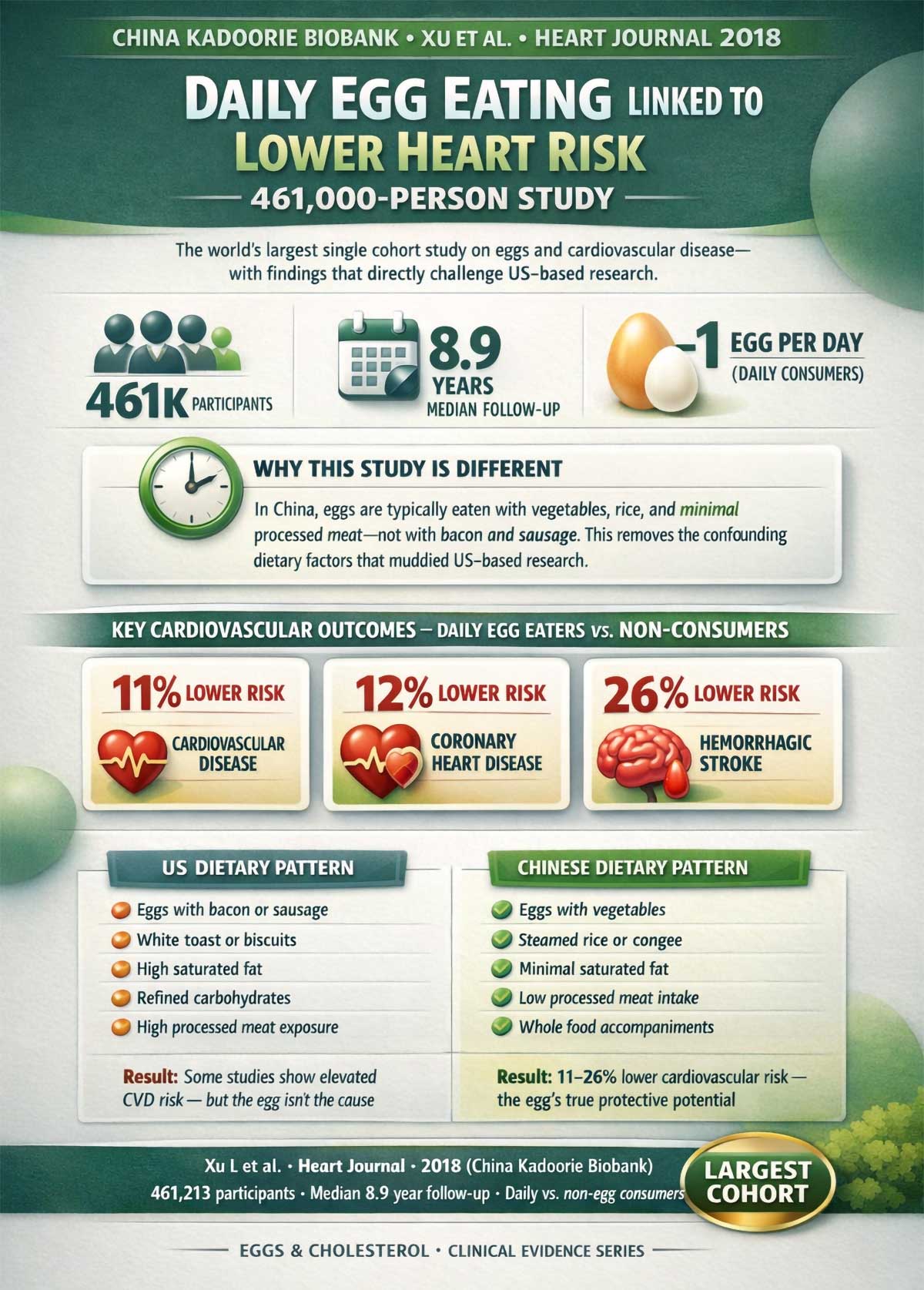

Compare that to a study from China. Xu et al. tracked 461,213 people over nearly nine years through the China Kadoorie Biobank. In China, eggs are commonly eaten with vegetables, rice, and minimal processed meat. The result? Daily egg consumption was linked to an 11% lower risk of cardiovascular disease, a 12% lower risk of coronary heart disease, and a 26% lower risk of hemorrhagic stroke compared to non-egg eaters.

Same food. Completely different outcome. The difference was everything else on the plate.

This is one of the clearest examples in nutrition science of context mattering as much as the food itself.

Eggs as a Weight Loss Tool—and What That Means for Your Heart

Eggs are dense in protein and highly satiating. Research by Vander Wal et al. showed that people who ate eggs at breakfast consumed fewer calories throughout the day compared to those who ate a bagel-based breakfast with the same calorie count. They fill you up faster and keep you full longer.

That’s not a small detail for heart health. Weight loss—even modest amounts—is one of the most effective ways to improve cardiovascular markers. It lowers blood pressure, improves insulin sensitivity, and reduces inflammation. If eggs help people eat less overall by cutting mid-morning hunger, they’re doing heart-protective work indirectly.

A randomized controlled trial by Blesso et al. (2013) tested three whole eggs per day in 37 adults with metabolic syndrome—a cluster of conditions that raise heart disease risk. All participants followed a carbohydrate-restricted diet. The result? HDL went up significantly. Large, benign LDL particles increased while small, dangerous ones decreased. Inflammation markers dropped. Insulin sensitivity improved.

These are the opposite of what you’d expect if eggs were truly dangerous. The carbohydrate-restricted context matters here. Eggs paired with refined carbs behave differently in the body than eggs paired with vegetables and healthy fats.

Who Should Still Pay Attention?

For most healthy adults, the evidence is reassuring. But “most people” doesn’t mean everyone. There are groups who should think more carefully.

People with type 2 diabetes sit in a more complicated space. A subgroup analysis in the Rong et al. 2013 meta-analysis—which covered nearly 264,000 participants across eight studies—suggested that diabetics may face a 54% higher stroke risk with egg consumption. That’s a number worth taking seriously.

But context matters again. The Fuller et al. trial (2015) tested high egg intake—about 12 eggs per week—in adults with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. Both groups followed a weight-loss diet. The result? No harmful effect on blood lipids. Both groups improved their HDL and other cardiovascular markers equally.

The takeaway for diabetics isn’t “avoid eggs.” It’s “manage your overall diet and weight, because that’s what drives your risk.”

Genetic hyper-responders are another group worth knowing about. About 25% of the population carries at least one copy of a gene variant called APOE4, which affects how the body processes cholesterol. These individuals tend to show a sharper rise in LDL in response to dietary cholesterol. Importantly, a 21-year Finnish study by Virtanen et al. (2016) followed over 1,000 middle-aged men and found no association between egg intake and heart disease risk—even in APOE4 carriers. That’s a surprising and reassuring finding. But it doesn’t mean APOE4 carriers should ignore their cholesterol numbers.

If you suspect you might be a hyper-responder—especially if heart disease runs in your family—the smartest move is simple: introduce eggs into your regular diet, get blood work done after a few weeks, and see how your body personally responds. Individual data beats population averages every time.

How to Eat Eggs for Your Heart—Not Against It

The research points to a clear bottom line. For most healthy adults, up to one egg a day is safe. The fear that eggs would fill arteries and cause heart attacks wasn’t supported by the largest, longest studies done on the subject.

But how you cook and pair your eggs does matter.

Cooking method that protects your heart: Poached, boiled, or lightly scrambled eggs cooked in a small amount of olive oil are your best bets. Frying in butter or cooking alongside fatty meats adds saturated fat that the studies suggest is far more damaging than the egg itself.

What makes the difference on your plate: Pair eggs with avocado for heart-healthy monounsaturated fats. Add spinach or any dark leafy green for fiber and micronutrients. Whole-grain toast works better than white bread. These combinations support the kind of cholesterol balance the research consistently links to lower risk.

What the research says to skip: Bacon, sausage, white biscuits, and processed breakfast meats. Not because of the egg—because of what those foods do on their own. The Western breakfast pattern that surrounds eggs in most US diets is doing far more cardiovascular damage than the egg at the center of the plate.

Eggs also carry nutrients worth noting. Choline supports brain function and liver health—one large egg provides about 147 mg of choline, roughly 27% of the daily adequate intake for most adults. It’s essential for neurotransmitter production and plays a key role in fetal brain development during pregnancy. Lutein and zeaxanthin, two carotenoids found in the yolk, support eye health and may reduce inflammation. Each egg provides roughly 200 to 300 micrograms of these compounds in a form the body absorbs well, thanks to the fat in the yolk.

Eggs are also typically affordable and easy to prepare—a combination that’s rarer in healthy eating than it should be.

The truth about eggs and cholesterol turns out to be less about the egg and more about the full picture—your diet, your genetics, your weight, and your overall lifestyle. For the vast majority of people, the egg is back on the menu. It just tastes better next to avocado than next to bacon.