Your gut hosts trillions of bacteria. These tiny organisms affect everything from digestion to mood. Fermented vegetables feed the good ones.

We analyzed human clinical trials, microbiological studies, and nutrient data to rank the top 15 fermented vegetables. No dairy. No soy products. Just vegetables that research shows can support your gut.

How We Ranked These Foods

We used a three-tier system based on evidence strength:

Gold Standard (Tier 1): Foods tested in human clinical trials with measurable gut health outcomes.

Strong Support (Tier 2): Foods backed by lab studies showing they produce beneficial compounds like short-chain fatty acids.

Promising Research (Tier 3): Foods with solid microbiological evidence but fewer human studies.

Let’s start with the most researched options.

Quick Reference Guide: All 15 Vegetables at a Glance

| Vegetable | Evidence Tier | Flavor Profile | Difficulty to Find | Best For Beginners |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sauerkraut | Gold | Tangy, salty | Easy | Yes ★ |

| Kimchi | Gold | Spicy, sour | Easy | Maybe |

| Fermented Carrots | Strong | Sweet, tangy | Moderate | Yes ★ |

| Fermented Beets | Strong | Earthy, sour | Moderate | Yes ★ |

| Lacto-Fermented Cucumbers | Strong | Salty, sour | Moderate | Yes ★ |

| Fermented Daikon | Strong | Crisp, sharp | Moderate | No |

| Fermented Mustard Greens | Strong | Bitter, tangy | Hard | No |

| Fermented Bamboo Shoots | Promising | Mild, earthy | Hard | No |

| Fermented Turnips | Promising | Sharp, earthy | Moderate | Maybe |

| Fermented Green Beans | Promising | Mild, tangy | Moderate | Yes ★ |

| Fermented Onions | Promising | Pungent, mellow | Moderate | Maybe |

| Fermented Cauliflower | Promising | Mild, tangy | Easy | Yes ★ |

| Fermented Chili Peppers | Promising | Spicy, complex | Moderate | No |

| Fermented Garlic | Promising | Mellow, sweet | Moderate | Maybe |

| Fermented Leafy Greens | Promising | Variable | Hard | No |

Find Your Perfect Fermented Vegetables

Answer 6 questions to get personalized recommendations

What's your main health goal?

How adventurous is your palate?

Have you eaten fermented vegetables before?

How sensitive is your stomach?

Do you follow any dietary restrictions?

How easy do you want it to be?

Tier 1: The Clinical Powerhouses

These vegetables have the strongest scientific backing. Human studies show they can change gut bacteria populations and improve digestive symptoms.

1. Sauerkraut (Fermented Cabbage)

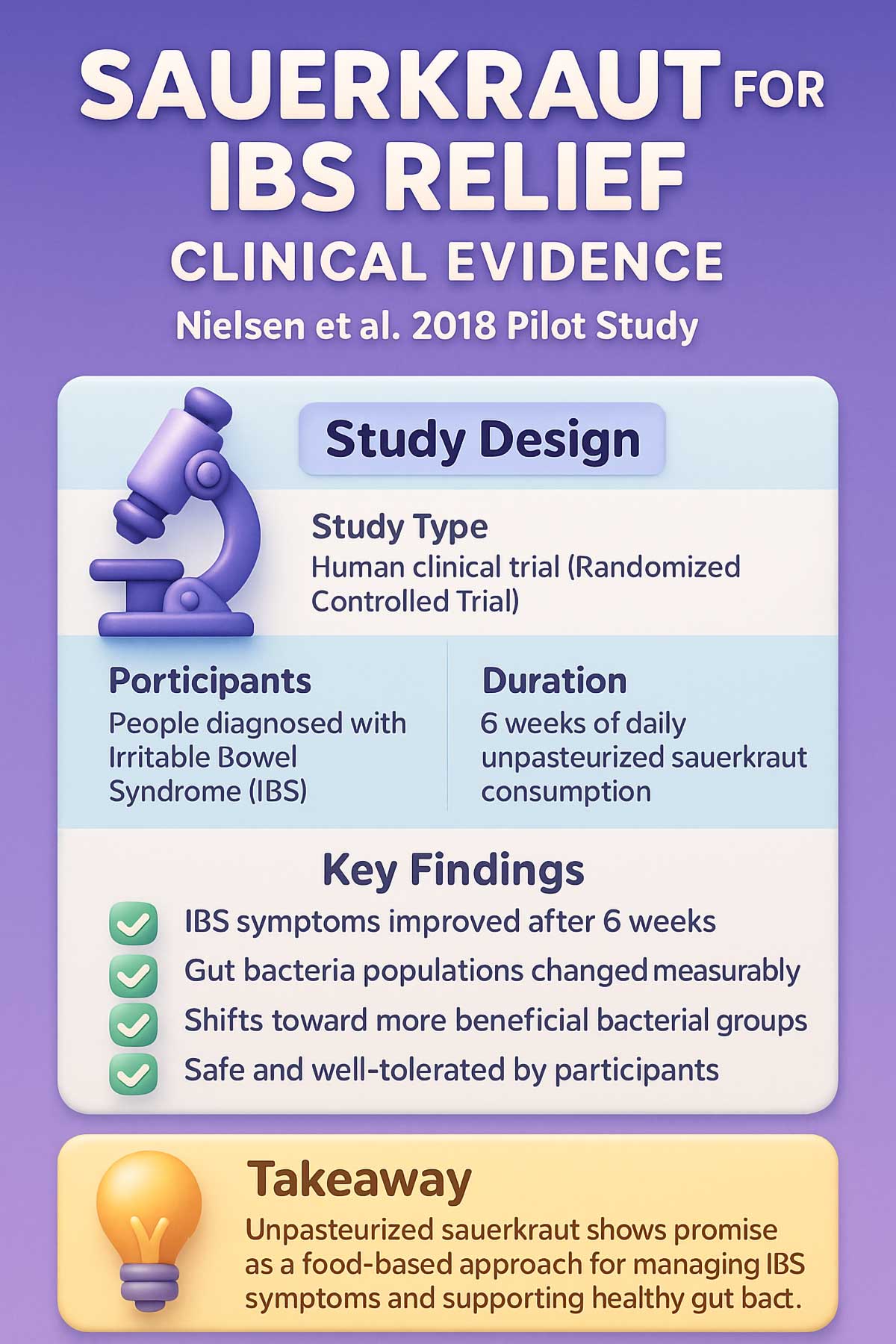

This takes the top spot for good reason. A 2018 pilot study by Nielsen and colleagues tested unpasteurized sauerkraut in people with IBS. Participants who ate sauerkraut daily for six weeks experienced symptom improvements and measurable changes in their gut bacteria populations. The researchers noted shifts toward more beneficial bacterial groups.

Sauerkraut contains multiple strains of lactic acid bacteria. The main players include Lactobacillus plantarum and Leuconostoc species. These bacteria produce organic acids that create an environment where beneficial microbes thrive.

Raw cabbage contains glucosinolates. During fermentation, these turn into compounds that research links to cancer protection. The bacteria break down plant fibers into food for your colon cells.

How to buy it: Look for jars in the refrigerated section labeled “unpasteurized” or “raw.” Shelf-stable versions have been heated, which kills the live bacteria.

Serving size: Start with 1-2 tablespoons daily. Your gut needs time to adjust.

Simple Homemade Sauerkraut

Ingredients:

- 1 medium cabbage (about 2 pounds)

- 1 tablespoon sea salt

Instructions:

- Remove outer cabbage leaves. Set one aside. Slice the rest thin.

- Place sliced cabbage in a large bowl. Add salt.

- Massage cabbage for 5-10 minutes until it releases liquid.

- Pack cabbage tightly into a clean glass jar. Press down firmly.

- Pour the liquid over cabbage. It should cover the vegetables completely.

- Place the reserved cabbage leaf on top. Weigh it down with a small glass or fermentation weight.

- Cover loosely. Leave at room temperature for 3-10 days.

- Taste daily after day 3. When it reaches your preferred tanginess, seal and refrigerate.

Storage: Keeps 2-6 months refrigerated.

2. Kimchi (Napa Cabbage and Radish Base)

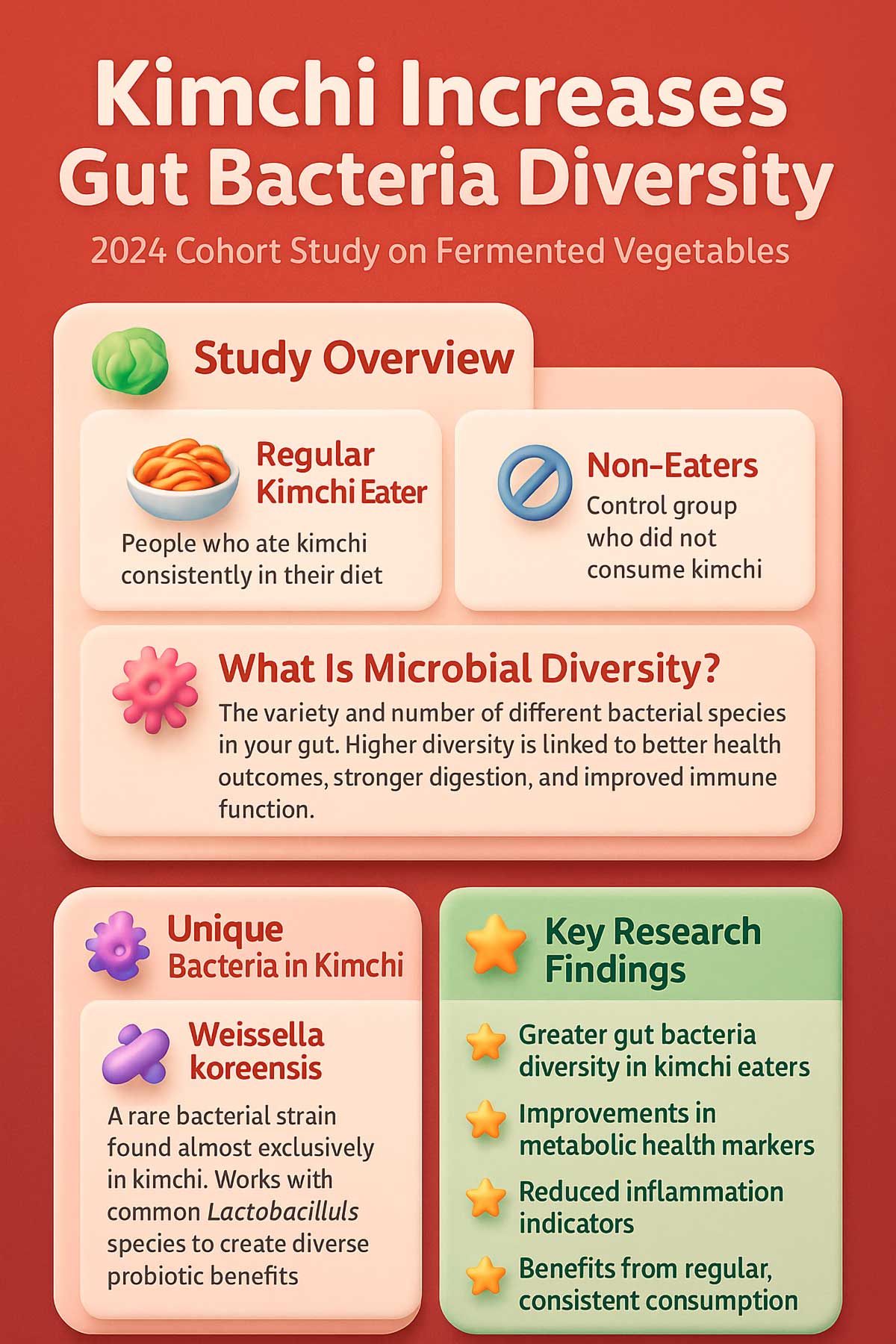

Multiple controlled trials show kimchi affects metabolism and inflammation markers. A 2024 cohort study examined regular kimchi eaters and found they had greater microbial diversity in their guts compared to non-eaters. The research team documented specific increases in bacterial species associated with better metabolic health.

What makes kimchi special? It contains Weissella koreensis, a bacterial strain rarely found in other fermented foods. This strain works alongside common Lactobacillus species to create a diverse probiotic mix.

The spicy, sour flavor comes from fermentation byproducts and chili peppers. If you’re new to fermented foods, the strong taste might take getting used to. Try mixing a small amount into rice or soup.

Types to try: Napa cabbage kimchi (baechu) is most common. Radish kimchi (kkakdugi) offers similar benefits with a different texture.

Storage tip: Keep it tightly sealed. The fermentation continues in your fridge, making it tangier over time.

Understanding Bacterial Strains: What Makes Each Vegetable Unique

| Vegetable | Primary Bacterial Strains | Unique Compounds Produced |

|---|---|---|

| Sauerkraut | L. plantarum, L. brevis, Leuconostoc | Glucosinolate metabolites, organic acids |

| Kimchi | Weissella koreensis, L. plantarum | Diverse organic acids, bioactive peptides |

| Fermented Carrots | Various LAB species | High SCFAs, enhanced carotenoids |

| Fermented Beets | LAB species | Nitric oxide precursors, betalains |

| Fermented Cucumbers | L. plantarum, Pediococcus | Organic acids, bacteriocins |

Tier 2: Strong Lab Evidence

These vegetables show impressive results in laboratory studies. Researchers have measured how they affect beneficial bacteria and produce helpful compounds.

3. Fermented Carrots

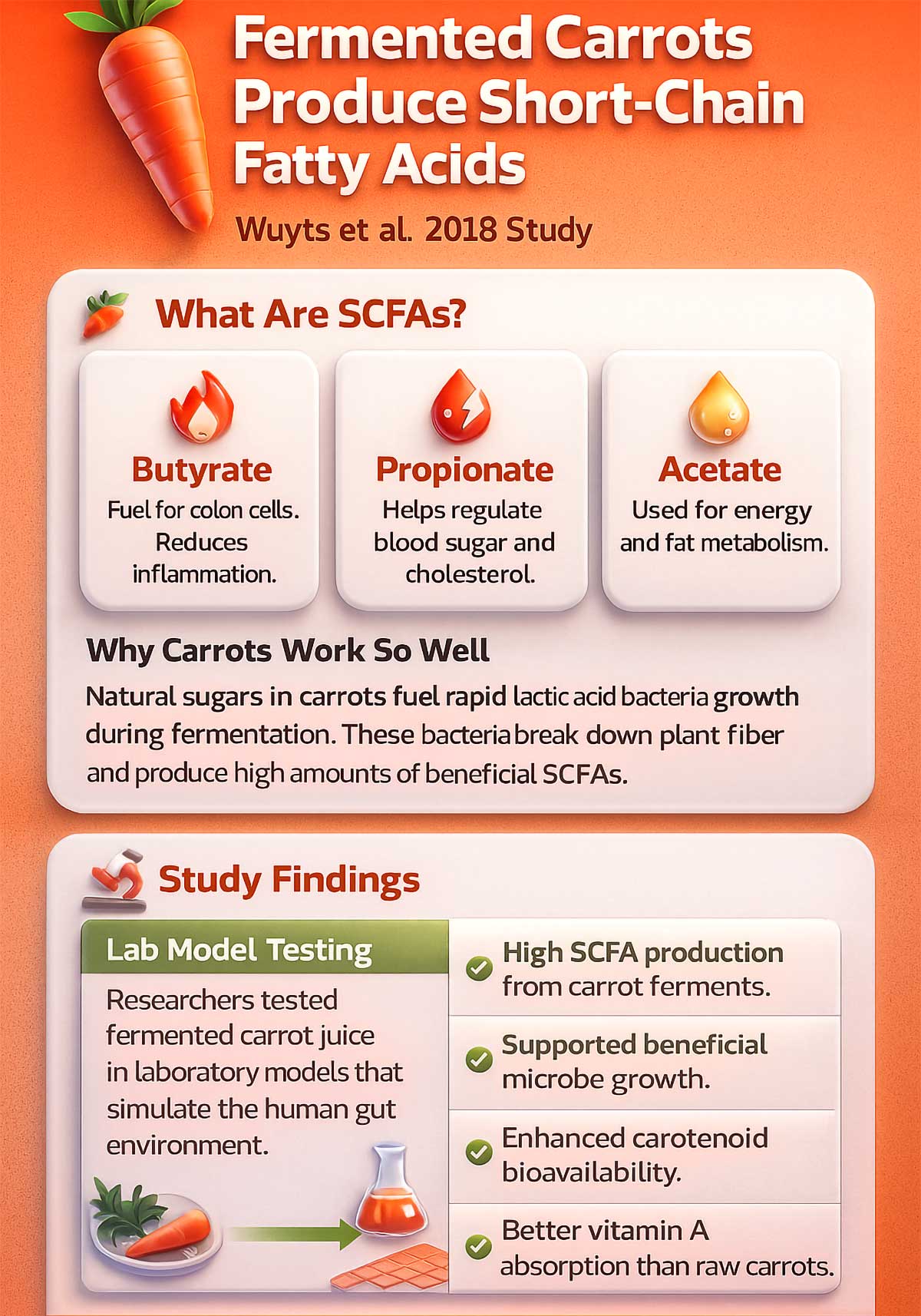

Carrots contain natural sugars that fuel rapid bacterial growth. A 2018 study by Wuyts and colleagues examined carrot ferments and found they produced high amounts of short-chain fatty acids. The research showed these ferments supported beneficial microbes in lab models. Short-chain fatty acids feed the cells lining your colon and help reduce inflammation.

The fermentation process also makes beta-carotene easier for your body to absorb compared to raw carrots. A study published in Frontiers in Microbiology documented diverse lactic acid bacteria with functional activity in carrot fermentations.

Flavor profile: Sweet and tangy. Less intense than sauerkraut or kimchi.

DIY option: Carrots are among the easiest vegetables to ferment at home. They stay crisp and rarely go bad if you use enough salt.

Beginner-Friendly Fermented Carrot Sticks

Ingredients:

- 1 pound carrots, cut into sticks

- 2 cups water

- 1 tablespoon sea salt

- 2 garlic cloves (optional)

- 1 teaspoon peppercorns (optional)

Instructions:

- Dissolve salt in water to create brine.

- Pack carrot sticks vertically in a clean jar.

- Add garlic and peppercorns if using.

- Pour brine over carrots, leaving 1 inch of space at the top.

- Weigh down carrots to keep them submerged.

- Cover loosely. Ferment 3-7 days at room temperature.

- Refrigerate when they reach desired tanginess.

Tip: Carrots stay crunchy. They’re ready when they taste pleasantly sour.

4. Fermented Beets

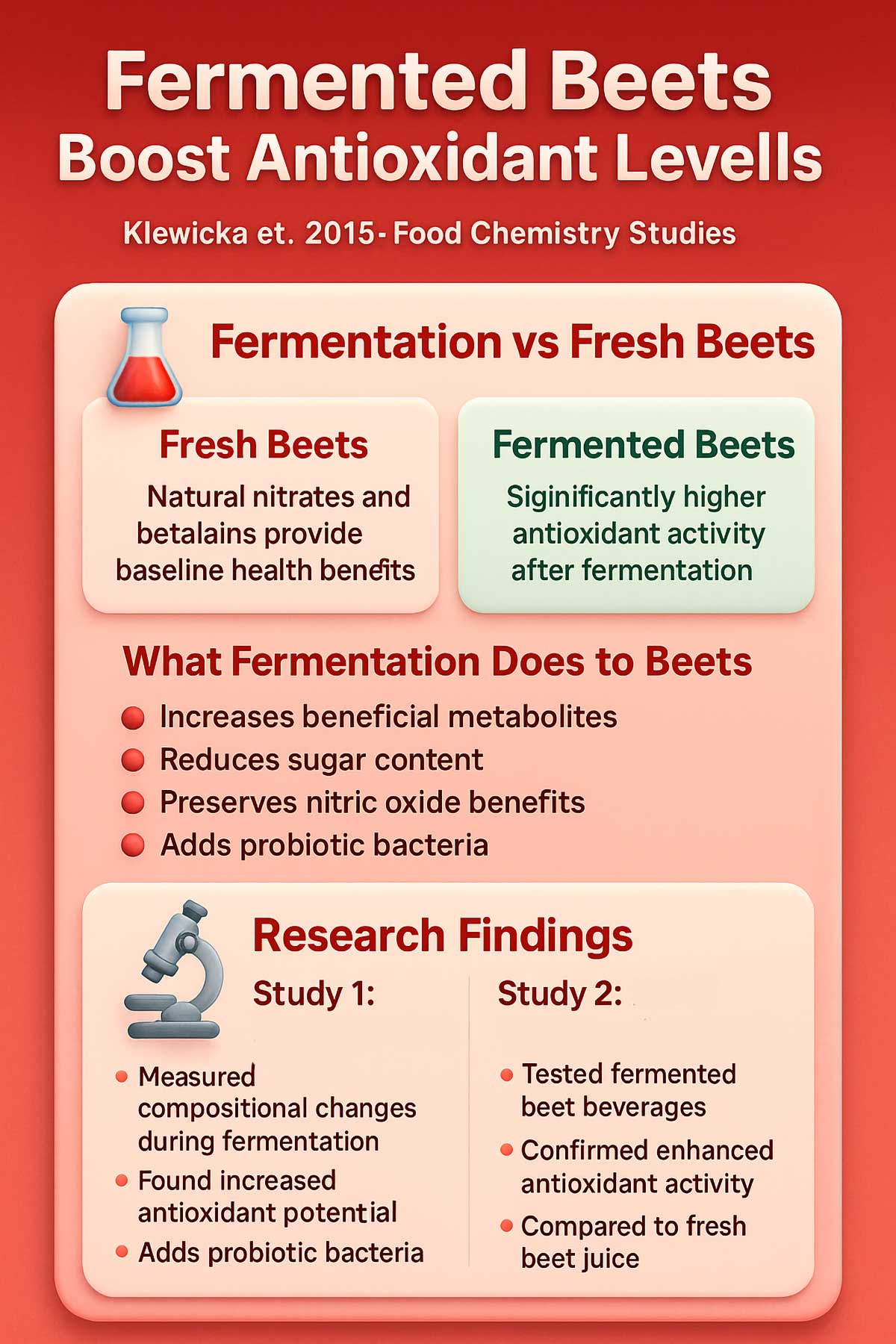

Beets offer a two-for-one benefit. They contain nitrates that support blood vessel function. Fermentation adds probiotic bacteria while reducing the sugar content.

Research by Klewicka and colleagues in 2015 found that fermentation significantly increased the antioxidant potential and beneficial metabolites in beets. A separate study in Food Chemistry examined fermented beet beverages and documented higher antioxidant activity compared to fresh beet juice.

Forms available: Lacto-fermented beet slices or beet kvass (a fermented drink made from beets).

Taste note: Earthy and slightly sour. Beet kvass has a milder flavor than eating the fermented slices.

What Are Short-Chain Fatty Acids?

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are the reason fermented vegetables matter so much. When bacteria ferment plant fiber, they produce three main SCFAs: butyrate, propionate, and acetate.

Butyrate: The primary fuel for colon cells. Studies link it to reduced colon inflammation and lower colon cancer risk.

Propionate: Travels to the liver where it helps regulate blood sugar and cholesterol production.

Acetate: The most abundant SCFA. Your body uses it for energy and fat metabolism.

These compounds don’t just feed you. They signal to your immune system, regulate inflammation, and strengthen your gut barrier.

Fermented carrots, beets, and onions rank high partly because they produce substantial amounts of SCFAs during fermentation.

5. Lacto-Fermented Cucumbers (Traditional Pickles)

Here’s where labels matter. Vinegar pickles from the shelf-stable aisle contain zero live cultures. True fermented pickles use only salt brine and time.

These traditional pickles contain high counts of L. plantarum and produce organic acids that help balance stomach pH. A 2020 review of traditional pickles confirmed that unpasteurized fermented cucumbers contain high lactic acid bacteria levels while vinegar pickles do not. Population studies link fermented pickle consumption with more diverse gut bacteria.

Shopping challenge: Most store pickles use vinegar, not fermentation. Check the ingredient list. You want: cucumbers, water, salt, spices. No vinegar. Find them in the refrigerated section.

Crunch factor: Real fermented pickles stay crunchier than vinegar versions because the bacteria don’t break down pectin the same way heat does.

6. Fermented Daikon Radish

Daikon differs from cabbage ferments because of its sulfur-rich compounds. These transform during fermentation into molecules that show antimicrobial effects against harmful bacteria while leaving beneficial strains alone.

Korean kkakdugi (cubed radish kimchi) harbors Leuconostoc species that thrive in this environment. A fermentation microbiology study documented that kkakdugi develops diverse lactic acid bacteria including Weissella and Leuconostoc species. Research shows these ferments develop different bacterial profiles than cabbage-based ones.

Texture: Crisp and refreshing. Less fibrous than raw daikon.

Spice level: Varies widely. Some versions use minimal chili; others pack serious heat.

7. Fermented Mustard Greens (Gundruk)

This Himalayan staple has been studied extensively in food science research. Traditional preparation involves sun-drying and fermentation, which creates unique organic acids not found in fresh greens.

A study on gundruk fermentation kinetics found it contains high densities of lactic acid bacteria along with beneficial organic acids. Researchers have documented its role in aiding digestion and appetite regulation in regions where it’s a dietary staple. A 2020 review by Tamang and colleagues described gut-related metabolites in traditional leafy-green ferments like gundruk.

Cultural context: Common in Nepal, Bhutan, and parts of India. Often used in soups and stews.

Availability: Harder to find in Western stores. Look in South Asian markets or consider making it if you have access to fresh mustard greens.

Understanding Glucosinolates: Why Cruciferous Vegetables Are Special

Cabbage, radish, turnips, mustard greens, and cauliflower all belong to the cruciferous family. They contain sulfur compounds called glucosinolates.

Fresh, these compounds have mild benefits. But fermentation transforms them. Bacteria break glucosinolates down into isothiocyanates and other metabolites. Research links these compounds to:

- Reduced cancer risk in population studies

- Antimicrobial effects against harmful gut bacteria

- Enhanced detoxification enzyme activity

This is why fermented cruciferous vegetables punch above their weight. You get probiotics plus these unique plant compounds working together.

Tier 3: Bioactive Specialists

These vegetables shine in specific ways. Some contain unique compounds that fermentation enhances. Others provide both probiotic bacteria and prebiotic fiber in one package.

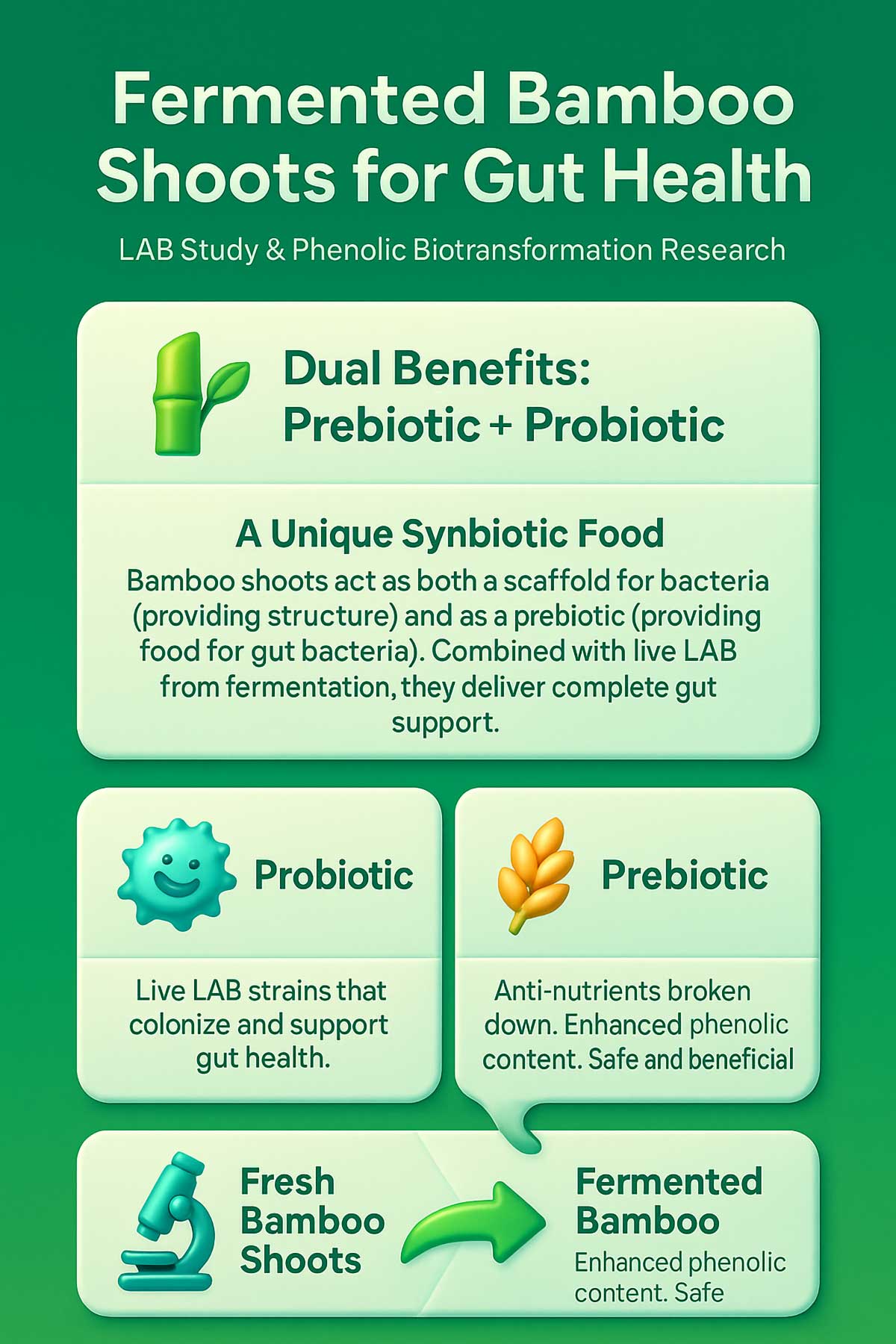

8. Fermented Bamboo Shoots

Fermentation breaks down anti-nutrients in bamboo shoots while boosting their fiber utility. The shoots act as a scaffold, providing structure that protects bacteria as they travel through your stomach.

A bamboo-shoot lactic acid bacteria study found that bamboo shoots develop LAB strains with prebiotic activity during fermentation. A separate study on phenolic biotransformation documented that fermentation enhances phenolic content and potential gut benefits. These compounds support your gut barrier, the layer of cells that controls what passes from your intestines into your bloodstream.

Preparation: Usually sliced thin. The texture softens during fermentation but maintains some bite.

Where to find them: Asian grocery stores carry fermented bamboo shoots in jars or vacuum-sealed packages.

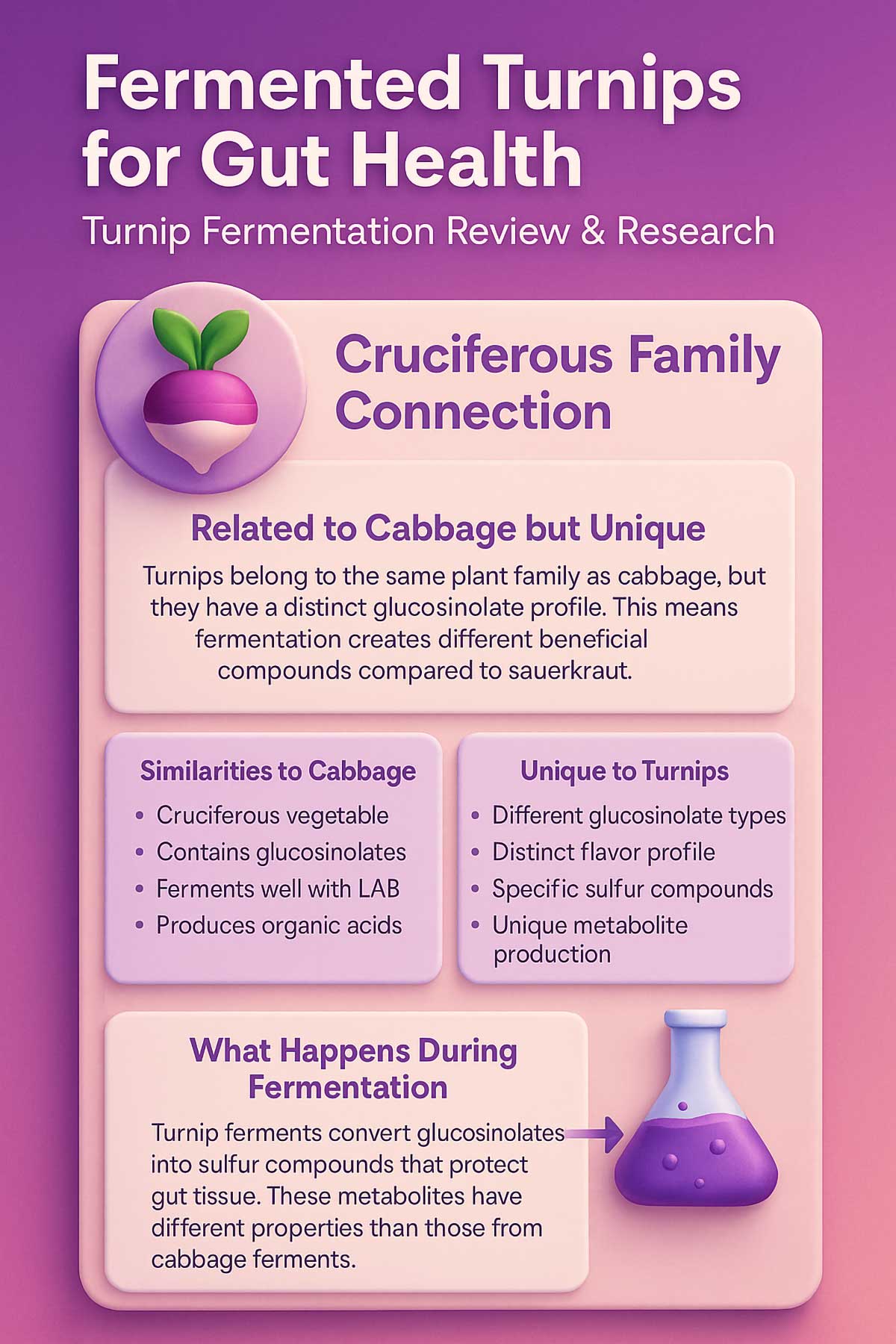

9. Fermented Turnips (Sauerrüben)

Turnips share family ties with cabbage. Both contain glucosinolates, but turnips have a distinct profile. During fermentation, these convert into sulfur compounds that protect gut tissue.

Research documented in a turnip fermentation review shows turnip ferments generate lactic acid bacteria and beneficial glucosinolate metabolites. Studies indicate turnip ferments increase antioxidant activity compared to fresh turnips. The evidence is moderate but growing.

Traditional use: Common in German and Eastern European cuisines. Often paired with fatty meats to aid digestion.

Taste: Earthy with a sharp, tangy finish. Milder than radish but stronger than carrots.

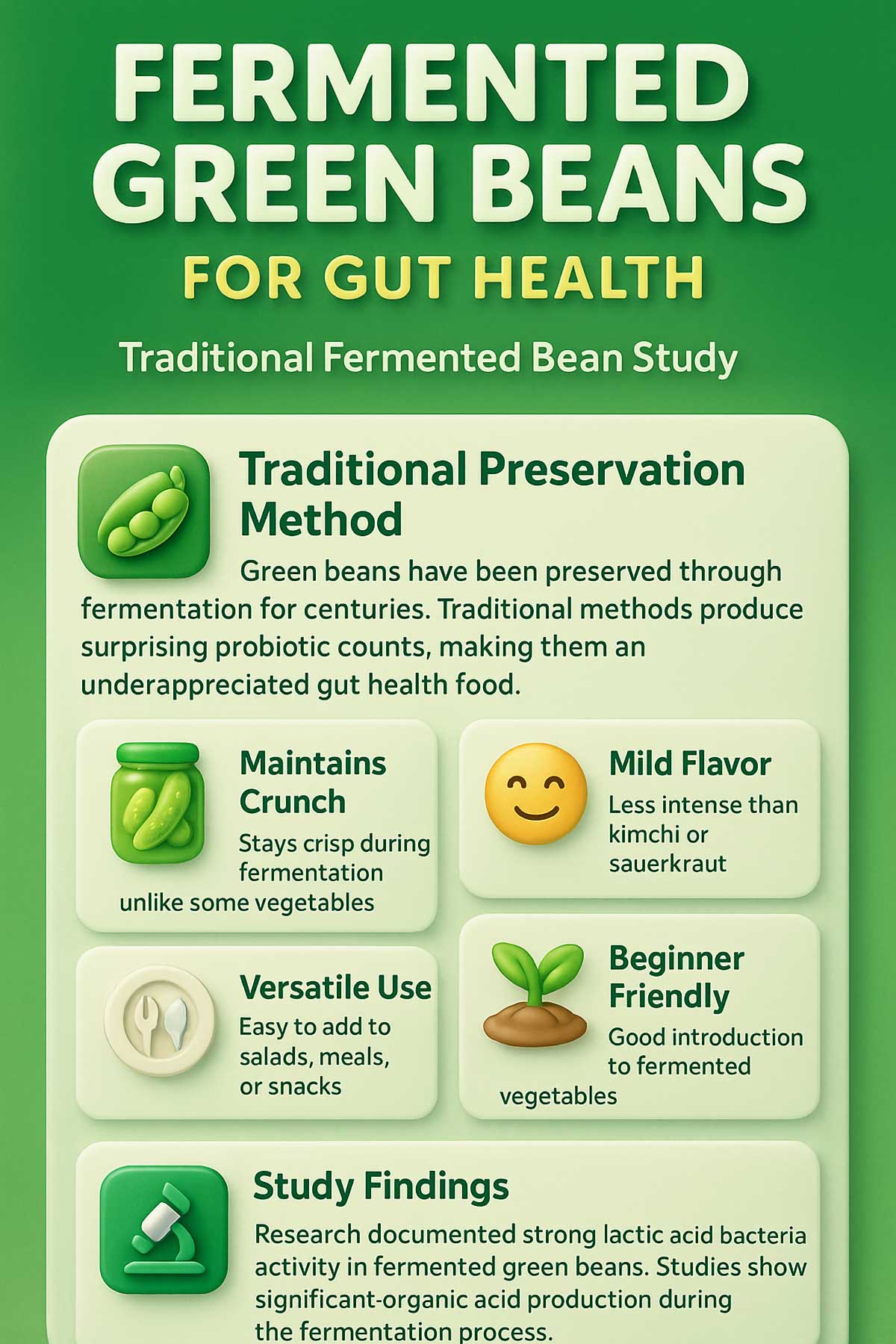

10. Fermented Green Beans

Traditional fermentation methods produce surprising probiotic counts in green beans. A study on traditional fermented beans found strong lactic acid bacteria activity and organic acid production. Studies document significant organic acid production, which discourages harmful bacteria while supporting beneficial species.

The evidence is mostly microbiological rather than clinical. That means we know the bacteria are there and active, but we have fewer studies on specific health outcomes in humans.

Crunch retention: Green beans can go soft if fermented too long. Look for batches that still have snap.

Serving ideas: Chop and add to salads, or eat straight from the jar as a snack.

11. Fermented Onions

Onions offer synbiotic benefits. They contain prebiotic fiber that feeds beneficial bacteria, plus the fermentation adds probiotic bacteria to the mix.

An onion fermentation study using lab models found that fermented onions promote Bifidobacteria growth. The pungent compounds that make raw onions harsh transform into gentler forms during fermentation.

Quantity matters: Onions are strong. A few fermented slices go a long way in terms of both flavor and gut impact.

Use them for: Topping burgers, mixing into grain bowls, or adding to eggs.

12. Fermented Cauliflower

Cauliflower appears in many mixed ferments like giardiniera. Its dense structure protects bacteria during transit through your stomach acid.

The vegetable contains glucosinolates that convert into sulforaphane. A review of fermented mixed vegetables documented that cauliflower in mixed ferments shows lactic acid bacteria increases and glucosinolate conversions. Research suggests fermentation may enhance the bioavailability of this compound, though more studies are needed.

Texture advantage: Cauliflower stays firm. It won’t turn mushy like some leafy greens can.

Mix it: Often fermented alongside carrots, peppers, and celery for variety.

Mixed Fermented Vegetables (Giardiniera Style)

Ingredients:

- 2 cups cauliflower florets

- 1 cup carrot slices

- 1 cup celery, chopped

- 1/2 cup red bell pepper, sliced

- 3 garlic cloves

- 1 tablespoon sea salt

- 2 cups water

- 1 teaspoon red pepper flakes (optional)

Instructions:

- Mix all vegetables in a large bowl.

- Dissolve salt in water.

- Pack vegetables into a half-gallon jar.

- Pour brine over vegetables until covered.

- Weigh down vegetables.

- Ferment 5-7 days, then refrigerate.

Uses: Salad topper, sandwich addition, or side dish.

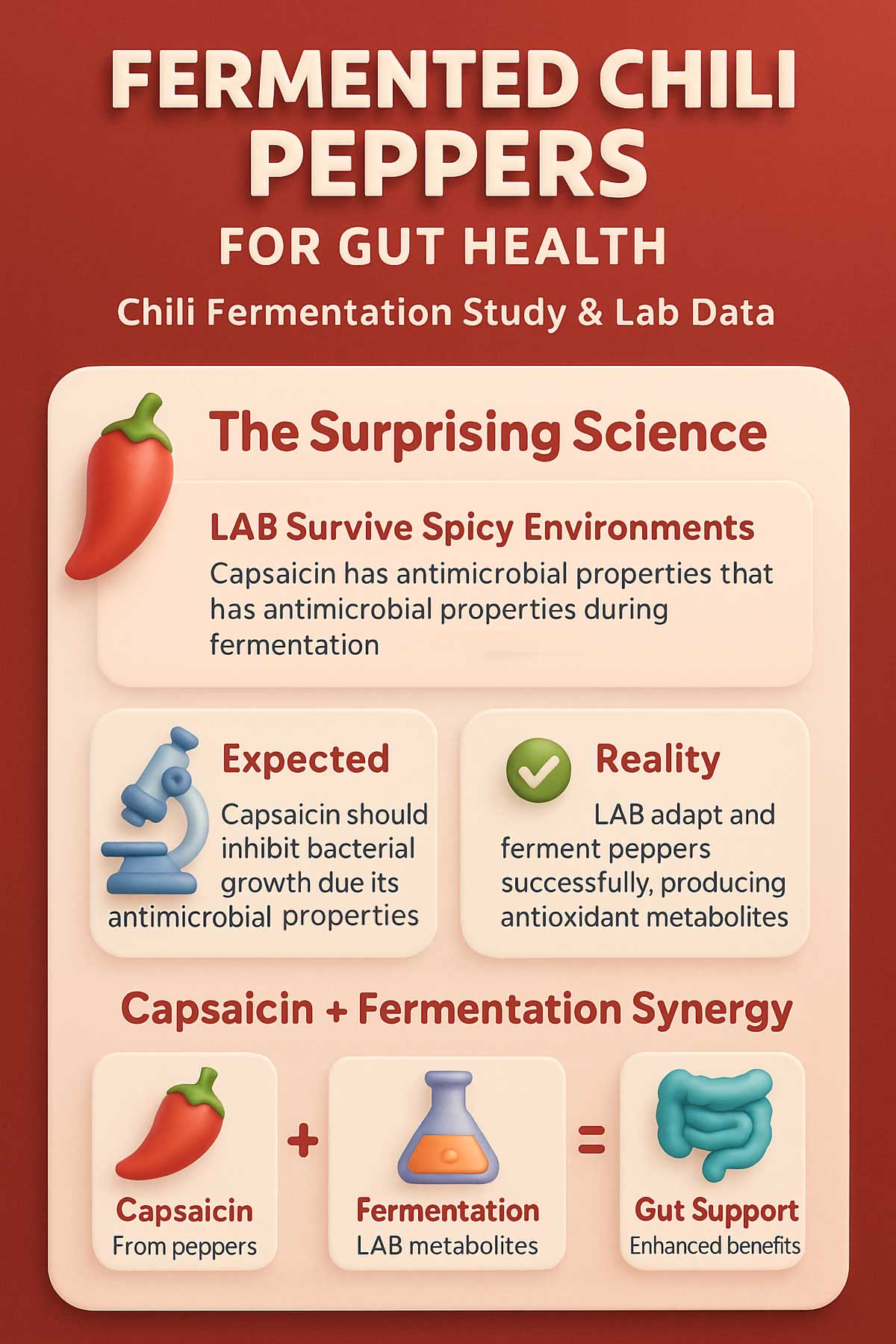

13. Fermented Chili Peppers

Lactic acid bacteria can tolerate and thrive in capsaicin-rich environments. That’s surprising because capsaicin has antimicrobial properties.

A chili fermentation study showed that lactic acid bacteria survive and ferment capsaicin-rich peppers while producing antioxidant metabolites. Lab data suggests capsaicin combined with fermentation byproducts may support the tight junctions in your gut lining. These junctions control permeability, determining what can pass through.

Heat level: Varies by pepper type. Start mild if you’re sensitive to spice.

Traditional versions: Mexican salsa, Asian chili pastes, and hot pepper relish all use fermentation.

14. Fermented Garlic

Fermentation reduces the harshness of raw garlic while enhancing its beneficial properties. A review on black and fermented garlic found that fermentation increases antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. Animal gut studies showed microbiome effects from fermented garlic consumption.

The allicin derivatives that form during fermentation show gut-modulating effects in research. These compounds become more stable and easier to absorb than fresh garlic’s compounds.

Methods: Honey-fermented garlic or brine-fermented cloves. Both work, but honey fermentation creates a sweeter result.

Patience required: Garlic takes several weeks to ferment properly. The cloves soften and develop a complex, mellow flavor.

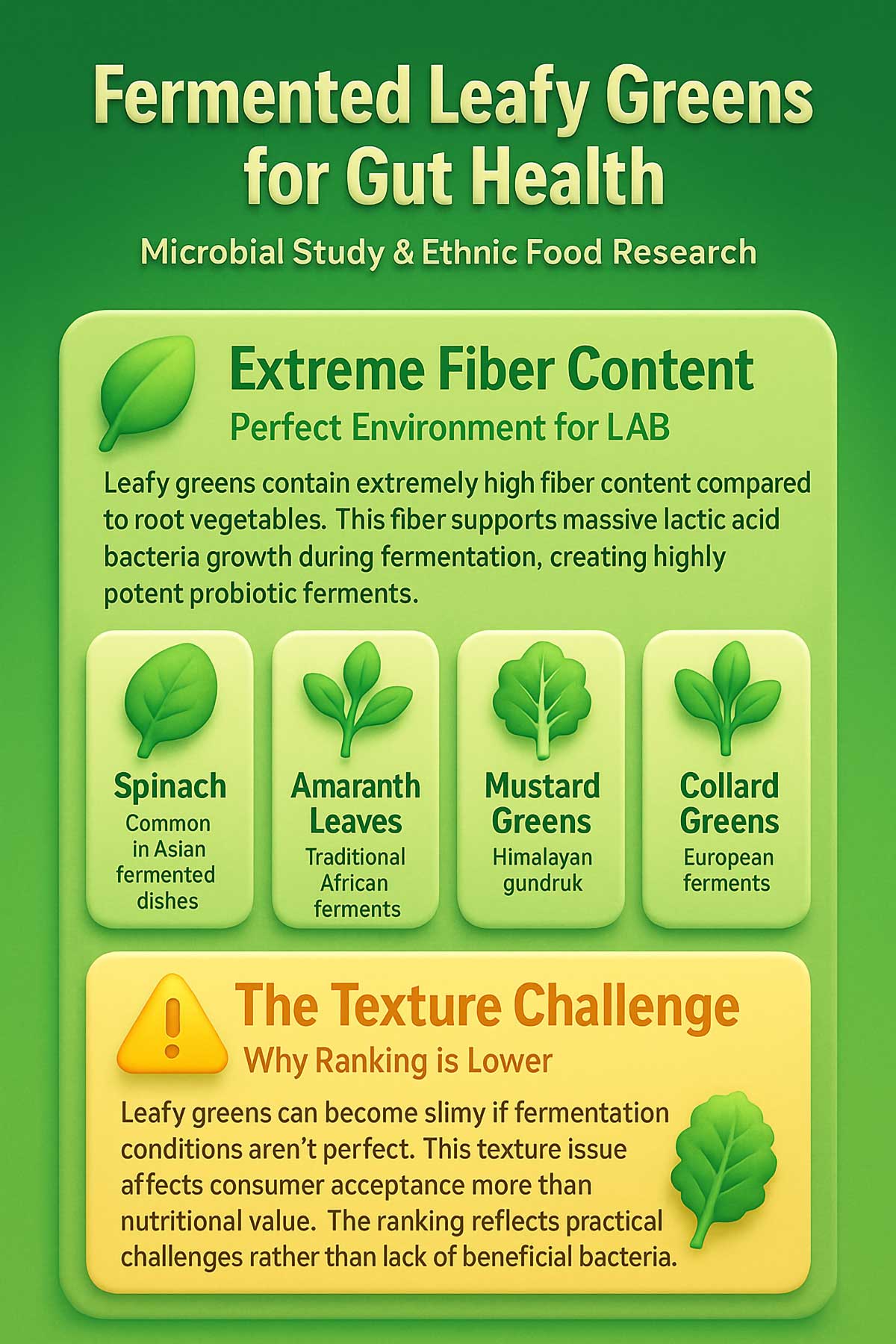

15. Fermented Leafy Greens (Spinach and Amaranth)

Leafy greens contain extremely high fiber content, which supports massive bacterial growth during fermentation. These ferments are traditional in Asian and African cuisines.

A fermented leafy-green microbial study documented that leafy-green ferments harbor lactic acid bacteria and produce gut-related metabolites. Traditional ethnic food studies of gundruk and similar ferments show high LAB diversity. The ranking reflects limited clinical data rather than lack of potential. Microbiological studies show strong bacterial activity, but we need more human trials.

Texture challenge: Leafy greens can become slimy if fermentation conditions aren’t right. This affects consumer acceptance more than nutritional value.

Where they’re common: Ethiopian cuisine uses fermented greens. Some Asian pickles include fermented spinach or similar leaves.

How Fermentation Changes Nutritional Value

Fermentation doesn’t just add bacteria. It transforms the vegetables themselves.

Vitamin Increases:

- B vitamins (especially B12 in some ferments): Bacteria produce these during fermentation

- Vitamin K2: Created by bacterial activity, especially in longer ferments

- Vitamin C: Can increase or decrease depending on fermentation time

Mineral Bioavailability: Fermentation reduces phytic acid and other anti-nutrients that bind minerals. This makes iron, zinc, and magnesium easier to absorb.

Protein Changes: Bacteria partially break down proteins into amino acids. This makes them easier to digest and may reduce allergenic potential.

Sugar Reduction: Bacteria consume sugars during fermentation. Fermented carrots and beets have less sugar than their raw versions.

Fiber Transformation: While total fiber stays the same, fermentation makes it easier to digest and creates compounds that feed beneficial bacteria.

Health Benefits by Goal: Which Vegetables to Choose

| Health Goal | Top 3 Vegetables | Why They Help |

|---|---|---|

| IBS Relief | Sauerkraut, Fermented Carrots, Kimchi | Clinical trial evidence, high SCFA production |

| Anti-Inflammation | Kimchi, Fermented Beets, Sauerkraut | Reduces inflammatory markers in studies |

| Digestive Comfort | Fermented Carrots, Green Beans, Cauliflower | Milder flavors, gentle introduction |

| Immune Support | Kimchi, Sauerkraut, Fermented Garlic | High bacterial diversity, antimicrobial compounds |

| Blood Sugar Balance | Kimchi, Fermented Beets, Fermented Onions | Metabolic study evidence |

| Maximum Diversity | Rotate all 15 | Different strains feed different gut bacteria |

Symptom-to-Vegetable Matcher

Select your health concerns to find the best fermented vegetables

What are your main health concerns?

How to Add Fermented Vegetables Safely

Your gut bacteria population will shift as you add fermented foods. That can cause temporary bloating or gas. Start small to minimize discomfort.

Daily Amounts by Experience Level

Week 1-2 (Beginners): 1-2 tablespoons daily

Week 3-4: 1/4 cup daily

Maintenance: 1/4 to 1/2 cup daily

Experienced: Up to 1 cup daily if tolerated

Best Times to Eat Fermented Vegetables

With meals: Aids digestion by adding beneficial bacteria and acids when food is present.

Before meals: May help with appetite control and prepares digestive system.

Not recommended: On a completely empty stomach first thing in the morning if you have a sensitive stomach. The acids can cause discomfort.

After antibiotics: Especially beneficial for rebuilding gut bacteria, but wait until you finish the antibiotic course.

The Start Low, Go Slow Rule

Begin with one tablespoon per day for three days. If you feel fine, increase to two tablespoons. Keep gradually increasing until you reach a quarter to half cup daily.

Some people experience a Herxheimer reaction when bad bacteria die off quickly. Symptoms include headache, fatigue, or digestive upset. These pass within a few days but can be avoided by starting with smaller amounts.

Who Should Be Careful

People with histamine intolerance or mast cell activation syndrome may react poorly to fermented foods. The fermentation process produces histamine, which these conditions make difficult to break down.

If you get headaches, hives, or digestive distress after eating fermented vegetables, talk to a health provider about possible histamine sensitivity.

Shopping vs. Making Your Own

Store-bought advantages: Consistent quality, tested for safety, convenient.

Homemade advantages: Cheaper, control over ingredients, satisfaction of DIY.

Both work fine. If buying, remember: Shelf-stable means dead bacteria. The fermentation produced beneficial acids that remain, but you won’t get live cultures. For maximum probiotic benefit, choose refrigerated options.

Smart Shopping: Label Reading Guide

What to Look For:

✓ “Unpasteurized” or “Raw” on the label

✓ Located in refrigerated section

✓ Ingredient list: vegetables, water, salt, spices only

✓ No vinegar (unless it’s listed after fermentation cultures)

✓ Cloudy brine (sign of active bacteria)

✓ “Contains live cultures” or “probiotics”

Red Flags:

✗ Shelf-stable (room temperature shelving)

✗ Vinegar as a primary ingredient

✗ “Pasteurized” on label

✗ Contains preservatives (sodium benzoate, potassium sorbate)

✗ Clear, transparent brine

✗ Very cheap price (real fermentation takes time and cost)

Price Reality Check: Real fermented vegetables cost more. Expect to pay $8-15 per jar. The fermentation process takes weeks, and you’re paying for live cultures and traditional methods.

Storage and Shelf Life

Fermented vegetables last months in the fridge. The cold slows fermentation but doesn’t stop it completely. They’ll get more sour over time.

Signs of spoilage: Mold on the surface, slimy texture, or foul smell. Surface mold can sometimes be scraped off if caught early, but when in doubt, throw it out.

Common Fermentation Problems and Solutions

Problem 1: My Ferment Smells Bad

Normal: Sour, tangy, slightly funky (like cheese)

Not Normal: Rotten, putrid, like garbage

Solution: If it smells rotten, discard and start over. Ensure vegetables stay submerged in brine.

Problem 2: Mold Appeared on Top

White film: Usually kahm yeast. Harmless but affects taste. Skim off and continue.

Fuzzy mold (green, black, pink): Discard everything. The jar may not have been clean enough.

Prevention: Keep vegetables submerged. Use clean equipment.

Problem 3: It’s Too Salty

Cause: Too much salt in the recipe.

Solution: Rinse fermented vegetables before eating. Or ferment longer so bacteria consume more salt.

Problem 4: Vegetables Got Mushy

Cause: Fermented too long or at too high a temperature.

Prevention: Ferment at 65-75°F. Check daily. Refrigerate sooner.

Problem 5: Nothing’s Happening (No Bubbles)

Cause: Too cold, not enough salt, or vegetables were treated with preservatives.

Solution: Move to a warmer spot. Wait longer. Use organic vegetables when possible.

Fermented Vegetables for Special Diets

Keto and Low-Carb Diets: Most fermented vegetables fit perfectly. They’re low in net carbs since bacteria consume sugars during fermentation. Best choices: sauerkraut, fermented cucumbers, cauliflower, and green beans.

Vegan and Vegetarian Diets: All vegetables on this list are plant-based. They provide B vitamins often lacking in plant-based diets, especially B12 in some long-fermented varieties.

Paleo Diet: All options align with paleo principles. Focus on sauerkraut, kimchi, fermented root vegetables, and fermented onions.

FODMAP Sensitivity: Fermentation reduces FODMAP content in some vegetables. Fermented carrots and green beans are usually better tolerated than raw versions. Avoid fermented onions and garlic during elimination phases.

Autoimmune Protocol (AIP): During reintroduction phases, start with fermented carrots or cucumbers. Avoid nightshade-based ferments (peppers, tomatoes) during elimination.

Pregnancy: Fermented vegetables are generally safe and beneficial during pregnancy. They provide folate and support immune function. Start with milder options like carrots if experiencing nausea.

How to Eat Fermented Vegetables: Pairing Ideas

Breakfast Ideas:

- Add sauerkraut to scrambled eggs or omelets

- Top avocado toast with fermented carrots or onions

- Mix fermented vegetables into breakfast hash

Lunch Options:

- Layer into sandwiches and wraps

- Toss into grain bowls with rice or quinoa

- Add to salads for tangy crunch

- Mix into tuna or chicken salad

Dinner Pairings:

- Serve alongside fatty meats (traditional pairing aids digestion)

- Top burgers or tacos

- Mix into stir-fries (add after cooking to preserve bacteria)

- Serve as a side dish with any protein

Snack Ideas:

- Eat straight from the jar

- Pair with cheese and crackers

- Add to hummus and vegetable platters

- Wrap in lettuce leaves with protein

Note: Don’t cook fermented vegetables if you want the probiotic benefits. Heat kills the bacteria. Add them to dishes after cooking or eat them raw.

Building Your Fermented Vegetable Rotation

You don’t need all 15 varieties. Pick three or four that appeal to you and rotate them weekly. Diversity matters more than quantity.

Try this approach: One mild option (carrots or green beans), one strong flavor (kimchi or sauerkraut), and one wild card from the specialty list. This gives your gut different bacterial strains and compounds.

Listen to your body. Some vegetables might agree with you more than others. That’s normal. Your gut bacteria composition is unique to you.

Your 7-Day Fermented Vegetable Challenge

Ready to improve your gut health? Here’s a simple way to start:

Days 1-2: Buy one jar of unpasteurized sauerkraut or fermented carrots. Eat 1 tablespoon with dinner.

Days 3-4: Increase to 2 tablespoons. Notice how your digestion feels.

Days 5-7: Add a second variety. Try kimchi or fermented pickles. Aim for 1/4 cup total daily.

Track how you feel. Many people notice changes in digestion, energy, or mood within a week.

Conclusion

Fermented vegetables deliver live beneficial bacteria, organic acids, and enhanced nutrients. The science is strongest for sauerkraut and kimchi, but other options offer real benefits too.

Adding these foods to your diet feeds your gut microbiome. A diverse microbiome associates with better digestion, stronger immune function, and improved overall health.

Fermented vegetables represent food as medicine. They’ve sustained human populations for thousands of years. Modern research now confirms what traditional cultures always knew: these foods support the ecosystem inside you.

Your gut microbiome is as unique as your fingerprint. What works brilliantly for one person might not be the best fit for another. That’s why variety matters. Rotate through different fermented vegetables to feed different bacterial species.

The evidence is clear for sauerkraut and kimchi. The research is promising for carrots, beets, and traditional pickles. The other options on this list offer benefits worth exploring, even if we need more human studies to confirm exactly how they work.

Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can. Your gut bacteria will respond to even small, consistent additions of fermented vegetables.

Diversity in your diet creates diversity in your microbiome. And a diverse microbiome is a healthy microbiome ready to support you.

FAQs

What are the best fermented vegetables for gut health?

Sauerkraut and kimchi have the strongest research backing. Both show benefits in human clinical trials for gut bacteria diversity and digestive symptoms. Fermented carrots, beets, and cucumbers also offer solid benefits with strong laboratory evidence.

Can I eat fermented vegetables every day?

Yes, most people can safely eat fermented vegetables daily. Start with 1-2 tablespoons and gradually increase to 1/4 to 1/2 cup per day. Listen to your body and adjust based on how you feel.

Do fermented vegetables need to be refrigerated?

Yes, if you want live probiotic bacteria. Refrigeration slows fermentation but doesn’t stop it. Shelf-stable fermented vegetables have been pasteurized, which kills beneficial bacteria but preserves the beneficial acids and nutrients.

Are pickles the same as fermented vegetables?

Not always. Vinegar pickles are not fermented and contain no live bacteria. True fermented pickles use only salt brine and contain probiotics. Check labels for “lacto-fermented” or “naturally fermented.”

How long do fermented vegetables last?

Properly stored in the refrigerator, fermented vegetables last 4-6 months. They become more sour over time but remain safe to eat as long as they smell tangy (not rotten) and show no mold growth.

Can you get enough probiotics from fermented vegetables?

Fermented vegetables provide billions of beneficial bacteria per serving. While exact counts vary, research shows regular consumption can positively affect gut bacteria populations. They offer a food-based alternative to probiotic supplements.

Which fermented vegetable is easiest to make at home?

Sauerkraut and fermented carrots are the easiest for beginners. They require only vegetables and salt, stay crisp during fermentation, and rarely spoil when basic guidelines are followed.

Do fermented vegetables help with bloating?

Research suggests they can, but start slowly. The fiber and bacteria in fermented vegetables support digestion, but introducing them too quickly can temporarily increase bloating as your gut adjusts.