You’ve seen the advice everywhere. Learn something new every day. Try a different route to work. Brush your teeth with your opposite hand. These tips promise to boost your brain’s ability to adapt and grow.

But what if this popular wisdom completely misses how neuroplasticity actually works?

Brain imaging studies tell a different story. When neuroscientists used MRI scanners and functional brain imaging to track what produces measurable brain changes, they discovered something that contradicts the scattered, daily-novelty approach. Real neuroplastic changes don’t come from trying something different every day. They result from sustained, focused practice of specific skills over periods of 6+ weeks, with timelines varying based on skill complexity.

This article examines ten major neuroimaging studies spanning two decades of research. These studies didn’t rely on self-reports or behavioral assessments alone—they captured actual structural changes in gray matter density, white matter connectivity, and functional activation patterns using sophisticated brain imaging technology. The pattern that appears across juggling studies, language learning protocols, and musical training programs is remarkably consistent: neuroplasticity requires depth of engagement, not breadth of exposure.

The findings have direct implications for anyone seeking to boost your brain’s adaptive capacity. The research reveals exactly what kind of practice produces real brain changes, how long it takes, and why the ‘learn something new daily’ advice misunderstands how your brain works.

Your 8-Week Neuroplasticity Quick Start

Want immediate action steps? Here’s what the research says works:

- Choose ONE skill today from the evidence-based options in this article (motor skills, language learning, or musical training).

- Block 30 minutes daily on your calendar for 8 weeks minimum. Mark these sessions as non-negotiable appointments.

- Set baseline metrics right now. Record your current ability level using objective measures specific to your chosen skill.

- Track weekly progress using measurable outcomes. Write down performance improvements every seven days.

- Commit to the timeline: No evaluation before week 6. Give your brain the time it needs to build new neural circuits.

The rest of this article explains why these steps work, what’s happening in your brain, and how to optimize your practice for maximum neuroplastic benefit.

Challenging the Popular Wisdom

The ‘learn something new every day’ recommendation dominates productivity blogs, wellness content, and social media posts about brain health. Readers scrolling through health feeds encounter this advice constantly. It sounds intuitively correct—after all, novelty stimulates the brain, and variety keeps life interesting.

When researchers actually examined what produces measurable neuroplastic changes using brain imaging technology, they discovered something that contradicts this scattered approach. The research reveals that meaningful structural and functional brain changes don’t emerge from trying something different every day. They result from sustained, focused practice of specific skills over extended periods.

This isn’t just theoretical neuroscience—it’s a practical finding with direct implications. Over the past two decades, researchers used MRI scanners, functional brain imaging, and diffusion tensor imaging to track exactly what happens when people commit to learning juggling, new languages, musical instruments, and motor skills. The pattern across these diverse studies is remarkably consistent: neuroplasticity requires depth of engagement, not breadth of exposure.

The evidence comes from ten major neuroimaging studies examining skill learning across different populations, age groups, and skill domains. These studies captured actual structural changes in gray matter density, white matter connectivity, and functional activation patterns. What they reveal challenges popular assumptions about how to train your brain.

Why the ‘Learn Something New Daily’ Advice Misses the Mark

The recommendation to learn something new every day has become common in wellness and productivity spaces, but it represents a basic misunderstanding of how neuroplasticity actually works. This advice typically stems from legitimate neuroscience concepts that have been oversimplified or misapplied.

Where the Advice Comes From

The ‘daily novelty’ recommendation appears to originate from several sources that contain kernels of truth but miss the deeper mechanism. First, there’s the well-known finding that novel experiences activate the brain and trigger dopamine release, which does support learning and attention. Second, the concept of ‘cognitive reserve’—the brain’s resilience against age-related decline—has been associated with lifelong learning and diverse experiences. Third, early animal studies showed that enriched environments with varied stimuli promoted neurogenesis and synaptic growth.

These legitimate findings were then simplified into the appealing, content-friendly advice to ‘try something new every day.’ The problem is that activation and stimulation aren’t the same as structural reorganization and consolidation. When you try something briefly and then move on, you’re providing acute stimulation without the sustained engagement required for the brain to commit resources to building and strengthening new neural circuits.

The Important Distinction: Cognitive Reserve vs. Structural Neuroplasticity

Cognitive reserve refers to the brain’s overall resilience built through lifetime experiences, education, and mental engagement—it helps protect against cognitive decline. The structural neuroplasticity documented in imaging studies refers to specific, measurable changes in brain tissue organization in response to skill practice. Both are valuable, but they represent different neurobiological phenomena with different timelines and mechanisms.

Diverse life experiences may build cognitive reserve over decades. The neuroplastic changes we’re discussing here—measurable increases in gray matter density, white matter modifications, and functional activation shifts—require focused skill practice over weeks to months. These are distinct processes serving different functions.

What Daily Novelty Gets Right (and Wrong)

The daily novelty advice does capture something accurate: novel experiences engage attention, activate multiple brain regions, and can boost mood and motivation through dopamine-mediated reward pathways. Variety in life experiences does support psychological wellbeing and may contribute to cognitive flexibility—the ability to shift between different mental frameworks and adapt to new situations.

Cognitive flexibility and structural neuroplasticity represent different phenomena. Brain imaging studies examining measurable neuroplastic changes tell a different story than the one suggested by ‘try something new daily.’ When researchers tracked participants learning juggling, studying new languages, or training in musical performance, they found that structural changes emerged only after sustained, repeated practice over weeks to months—not from brief, scattered exposure.

The Core Principle the Research Reveals

The neuroimaging literature demonstrates that meaningful neuroplastic changes follow a specific developmental trajectory. Participants in successful studies didn’t dabble in their chosen skill for a day or week before moving on. They engaged in intensive, repeated practice of the same skill, performing the same actions or cognitive processes hundreds or thousands of times over extended periods.

A landmark 2004 study by Draganski and colleagues examined adults learning to juggle over three months. Participants practiced daily, working on the same basic juggling pattern repeatedly. Brain scans revealed increased gray matter density in visual-motion processing areas after this sustained practice period. When participants stopped practicing in a 2006 follow-up study, these changes partially reversed over subsequent months—demonstrating that structural modifications were directly tied to ongoing skill engagement.

This pattern reveals the core mechanism: the brain builds and strengthens neural circuits through repeated activation and refinement, not through novelty exposure. Each repetition doesn’t just re-activate the same neurons; it progressively modifies synaptic strengths, promotes myelination of relevant pathways, and triggers structural changes in gray matter density and white matter connectivity. These processes require time and consistency—they can’t be rushed through daily skill-hopping.

| Skill Domain | Minimum Commitment | First Detectable Changes | Robust Changes | Optimal Practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Motor Skills | 6-8 weeks | 4-6 weeks | 8-12 weeks | 5-7x/week, 20-40 min |

| Complex Motor Skills | 8-12 weeks | 6-8 weeks | 12+ weeks | 5-7x/week, 30-45 min |

| Language Learning | 12-16 weeks | 8-12 weeks | 16+ weeks | Daily, 45-60 min |

| Musical Training | 16+ weeks | 12+ weeks | 24+ weeks | Daily 45-60 min + weekly lessons |

What Brain Imaging Studies Actually Show

The research examining skill-learning neuroplasticity represents some of the most rigorous neuroscience conducted over the past two decades. These studies employed sophisticated brain imaging technologies to track structural and functional changes in real-time as participants acquired new skills. The findings across different research groups, imaging modalities, skill domains, and populations provide a robust evidence base for understanding how learning reshapes the brain.

The Research Methodology and What Makes It Credible

Unlike behavioral studies that infer brain changes from performance improvements, these neuroimaging studies directly visualized and measured structural modifications. Researchers used voxel-based morphometry to detect changes in gray matter density, diffusion tensor imaging to track white matter structural connectivity, and functional MRI to capture activation pattern shifts.

Participants underwent baseline scans before training began, follow-up scans at set intervals during training, and in some cases, additional scans after training ceased to examine whether changes persisted or reversed. The power of this approach lies in its objectivity. Gray matter density changes, white matter fractional anisotropy modifications, and functional activation patterns can’t be faked or influenced by participant expectations.

What Brain Imaging Actually Measures

Many readers won’t be familiar with technical neuroimaging terms. Here’s what these measurements actually detect:

Gray Matter Density

This refers to more neural cell bodies, synapses, and support cells in specific brain regions. Think of it like building more muscle fibers in worked muscles—the tissue becomes denser and more capable. Researchers measure this using voxel-based morphometry (VBM) on structural MRI scans. When studies report ‘increased gray matter density,’ they’re documenting actual tissue changes in specific brain areas.

White Matter Connectivity

White matter consists of myelinated axons—the communication cables connecting different brain regions. Increased myelination means thicker insulation around these cables, which speeds signal transmission. This is like upgrading from dial-up to fiber-optic internet. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) measures fractional anisotropy, which indicates white matter structural integrity and organization.

Functional Activation Patterns

These represent more efficient, selective neural firing as skills become automatic. An expert driver uses less mental effort than a beginner performing the same task. Functional MRI (fMRI) measures blood oxygen levels during task performance, revealing which brain regions are active and how efficiently they operate.

The Pattern That Appears Across Studies

Despite examining different skill types, age groups, and training durations, the studies reveal a consistent developmental pattern. Neuroplastic changes unfold in stages, progressing from early functional modifications to later structural consolidation.

In the initial days to weeks of practice, functional brain imaging reveals changes in activation patterns—regions involved in the skill show altered response magnitudes or refined selectivity as the brain optimizes its processing strategies. These functional changes precede and predict subsequent structural modifications.

After continued practice over weeks to months, structural imaging begins detecting measurable changes in gray matter density or white matter connectivity. A 2012 review by Zatorre and colleagues examined learning-driven changes across music, speech, and language domains. The review synthesized findings from multiple imaging modalities—fMRI, structural MRI, and DTI—showing that sustained skill practice produces coordinated changes in functional activity, structural gray matter, and white-matter connectivity across sensory and motor domains.

These structural changes appear specifically in brain regions relevant to the practiced skill—visual-motion areas for juggling, language pathways for second language learning, motor and auditory regions for musical training. The anatomical specificity confirms that changes result from the particular skill practiced, not from general effects of effort or attention.

The Time Course of Neuroplastic Development

The timeline for detecting measurable changes varies across skill domains and imaging modalities, but several studies provide specific benchmarks.

Karni and colleagues in 1995 demonstrated that motor sequence learning produced expansion of motor cortex representations within 4-6 weeks of practice. This study examined eight adults practicing a simple finger-tapping sequence repeatedly. Functional MRI revealed slow, experience-dependent expansion of primary motor cortex activation after this repeated skill practice—documenting how sustained engagement reshapes cortical organization.

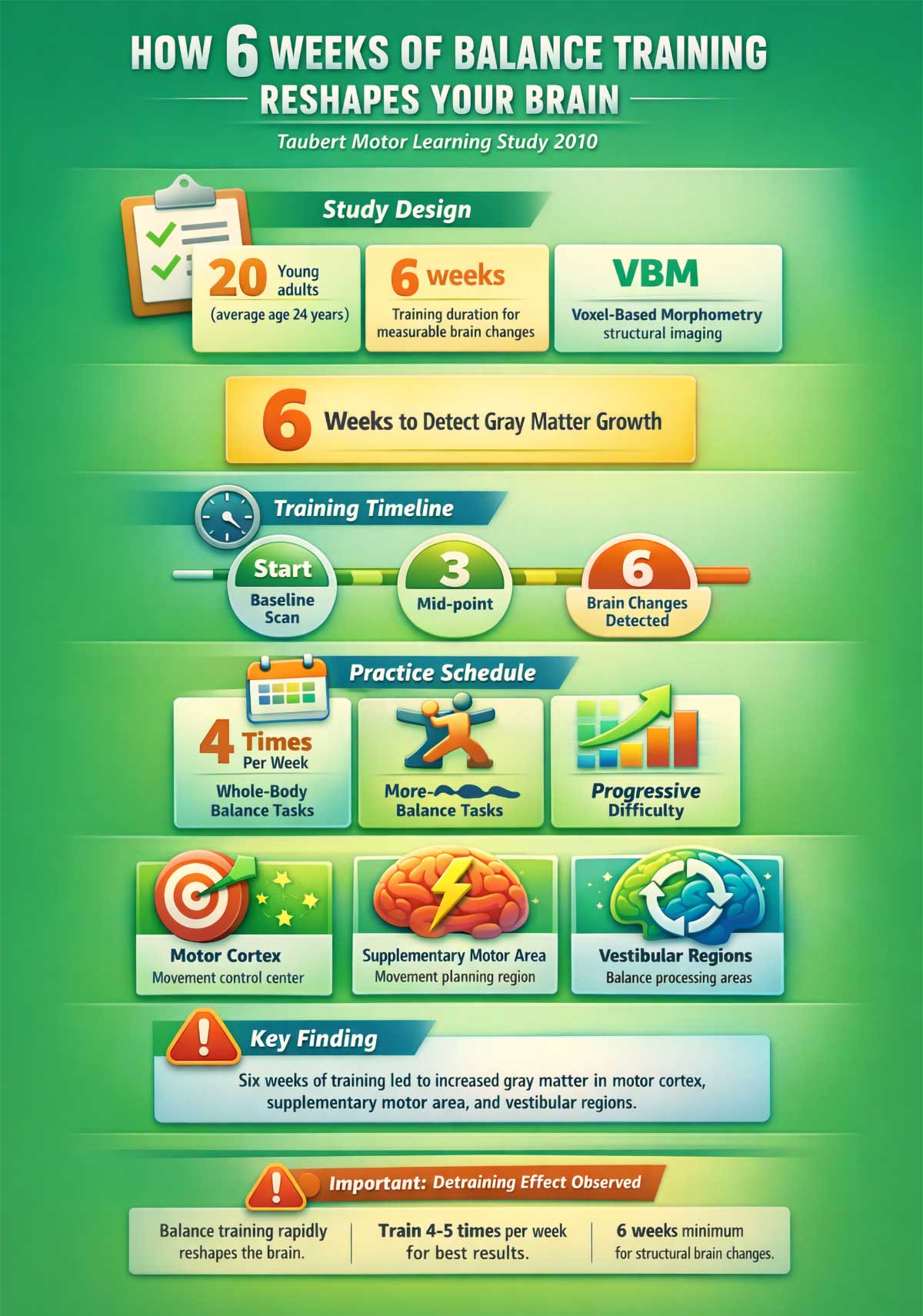

Taubert and colleagues in 2010 detected gray matter volume increases in motor and vestibular regions after 6 weeks of balance training. Twenty young adults practiced whole-body balance tasks four times weekly. Structural MRI using voxel-based morphometry showed gray matter volume increases in motor cortex, supplementary motor area, and vestibular regions during learning. When training ceased, some reversal occurred—confirming that ongoing practice maintains structural changes.

These motor skill studies represent the fastest timelines documented in the literature. More complex skills require longer developmental periods. The landmark juggling studies by Draganski mentioned earlier documented gray matter density increases after three months of daily practice. When participants stopped practicing, these changes partially reversed over subsequent months—about 50% decline rather than complete return to baseline. This demonstrates that structural modifications were directly tied to ongoing skill engagement, though some consolidation persists.

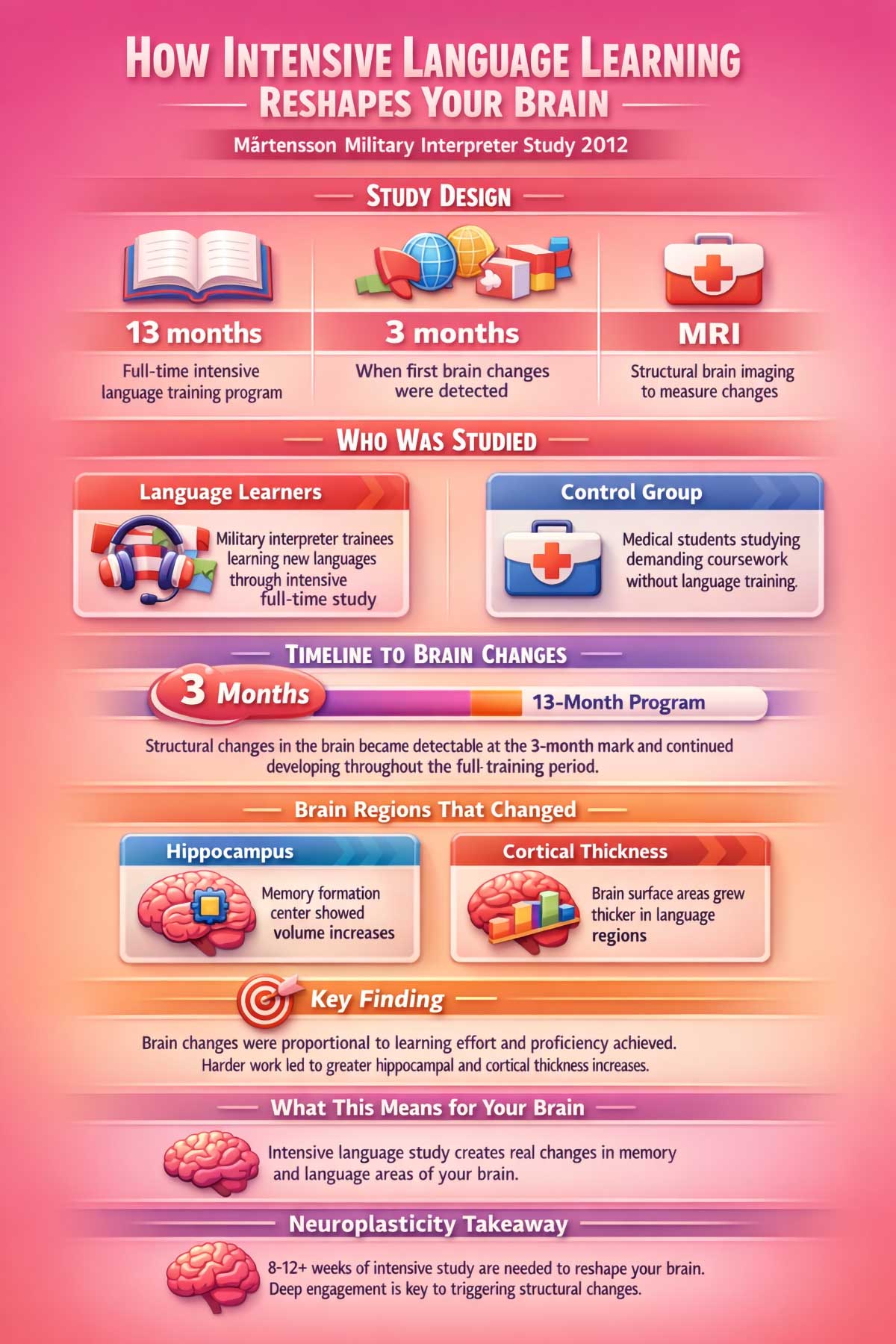

Language learning studies show even longer timelines. Mårtensson and colleagues in 2012 examined military interpreter trainees engaged in intensive 13-month language programs. These recruits participated in demanding full-time study compared to medical student controls. Structural MRI measured cortical thickness and hippocampal volume at the 3-month assessment point. Hippocampal and cortical thickness changes appeared proportional to learning effort and proficiency achieved, with changes continuing to develop throughout training.

Schlegel and colleagues in 2012 tracked white matter structural changes over 9 months of intensive Chinese language study. Sixteen English-speaking adults enrolled in demanding coursework. Diffusion tensor imaging revealed white-matter structural changes—specifically increased fractional anisotropy—in language-related pathways, particularly the left arcuate fasciculus connecting language processing regions. These white matter modifications took months to develop and reflected the brain building more robust connectivity between regions that must coordinate during language use.

Musical training demonstrates the longest documented developmental trajectories. Hyde and colleagues in 2009 followed children aged 5-7 receiving keyboard lessons over 15 months. Thirty-one children participated, with 15 receiving structured lessons plus daily home practice. Structural MRI using voxel-based morphometry detected structural brain changes in motor and auditory cortex regions, with corpus callosum changes linked to practice amount. The corpus callosum connects left and right brain hemispheres, and its modification reflects the bilateral coordination demands of musical performance.

Cross-sectional studies comparing professional musicians to amateurs and non-musicians revealed dose-dependent relationships. Gaser and Schlaug in 2003 used structural MRI to compare these groups. Professional musicians showed increased gray matter in motor, auditory, and visuospatial regions compared to amateurs, who in turn showed more than non-musicians. This gradient suggests that neuroplastic changes accumulate progressively over years of sustained practice.

What the Changes Actually Mean

The structural modifications documented in these studies aren’t merely markers—they have functional significance. Increased gray matter density in task-relevant regions reflects better neural resources devoted to processing the practiced skill. White matter changes indicate more efficient communication between brain regions that must coordinate during skilled performance. Functional activation changes demonstrate refined, more selective neural responses as expertise develops.

These changes support improved performance. Participants in the studies didn’t just show brain changes—they showed corresponding skill improvements that correlated with the magnitude of neural modifications. The brain reorganization enabled more efficient, accurate, and automatic performance of the practiced skills.

| Myth | What Research Shows | Source Study |

|---|---|---|

| Learn something new every day | Depth over breadth—sustained practice (6+ weeks) drives structural changes | Draganski 2004, 2006 |

| Brain training games create lasting changes | Domain-specific practice required; minimal transfer to unrelated tasks | Zatorre 2012 review |

| Changes happen in 21 days | Motor: 4-12 weeks; Language: 12-16 weeks; Music: 16+ weeks minimum | Multiple studies |

| Once learned, changes are permanent | Partial reversal (about 50%) occurs when practice stops completely | Draganski 2006, Taubert 2010 |

The Essential Role of Consistency Over Novelty

The neuroplasticity literature reveals a finding that directly challenges the ‘learn something new daily’ advice: depth of practice matters far more than breadth of exposure for driving measurable structural brain changes. While novel experiences certainly activate the brain and may support cognitive flexibility and psychological wellbeing, the documented neuroplastic changes captured in imaging studies require sustained, repeated engagement with the same skill or domain over extended periods.

Why Repetition Drives Structural Change

The mechanism underlying experience-dependent neuroplasticity involves progressive strengthening and refinement of neural circuits through repeated activation. When you practice a skill, specific populations of neurons fire in coordinated patterns. With repeated practice, several neurobiological processes unfold.

Synaptic connections between co-activated neurons strengthen through long-term potentiation mechanisms. Unused synapses are pruned away to increase efficiency. Myelin insulation around frequently-used axons thickens to speed signal transmission. Metabolic support systems expand to meet the energy demands of active circuits.

These processes require time and repetition to develop. A single exposure to a novel task activates relevant brain regions but doesn’t provide sufficient repetition for structural consolidation. The brain needs to receive consistent signals that ‘this skill matters and will be used repeatedly’ before committing resources to building robust neural infrastructure to support it.

Evidence from Motor Learning Studies

The motor learning studies show how consistency drives neuroplastic change. The Karni finger-tapping study had participants practice a simple sequence repeatedly over 4-6 weeks. This wasn’t about novelty—participants performed the same sequence hundreds or thousands of times. The resulting expansion of motor cortex representations emerged specifically because of this sustained, repeated engagement.

A 2011 review by Dayan and Cohen synthesized findings from multiple motor learning studies. The review examined fast and slow stages of plasticity, showing that motor learning induces region-specific cortical reorganization and connectivity changes through both rapid and gradual mechanisms. The key finding: continued neuroplastic adaptation occurs when task demands increase systematically. This means neuroplasticity isn’t just about initial learning but about continued adaptation to increasing challenges within a practiced domain.

The brain devoted more cortical territory to representing the practiced movement sequence because that representation was activated consistently and frequently. Similarly, the Draganski juggling studies involved daily practice of the same basic juggling pattern over three months. Participants weren’t learning new juggling tricks every day—they were refining and consolidating their ability to perform a specific motor-visual coordination skill.

The gray matter increases in visual-motion processing areas reflected the brain’s structural commitment to supporting this repeatedly-practiced skill. The Taubert balance study reinforces this pattern. Participants practiced whole-body balance tasks four times weekly for six weeks—sustained engagement with the same skill domain. The resulting gray matter volume increases in motor cortex, supplementary motor area, and vestibular regions emerged from this consistent practice schedule, not from trying different balance challenges daily without consolidation.

Language Learning Requires Deep Processing

The language learning studies show that neuroplastic changes require depth rather than breadth. Mårtensson’s military interpreter trainees engaged in intensive, focused study of specific languages over 13 months. The hippocampal and cortical thickness changes detected at three months reflected deep processing and integration of linguistic knowledge—vocabulary, grammar, phonology, and pragmatic usage patterns all practiced intensively and repeatedly.

Schlegel’s study of adults learning Chinese as a second language involved nine months of intensive coursework. The white matter structural changes in language pathways, particularly increased fractional anisotropy in the left arcuate fasciculus, resulted from sustained engagement with a single language. Participants weren’t sampling multiple languages briefly—they were deeply learning one language system, allowing their brains to build robust connectivity between language processing regions to support fluent comprehension and production.

The intensity and focus of these language protocols contrasts sharply with casual learning approaches. These weren’t learners using apps for 10 minutes daily while also dabbling in other skills—they were engaged in demanding, immersive study that required sustained mental effort and produced progressive skill development over months.

Musical Training and Progressive Skill Development

Musical training provides perhaps the clearest example of how sustained practice of a single skill domain produces extensive neuroplastic changes. Hyde’s study followed children receiving keyboard lessons over 15 months—regular weekly lessons plus daily home practice focused on developing piano technique and repertoire. The structural brain changes in motor and auditory cortex regions, plus corpus callosum modifications, emerged from this long-term commitment to developing musical skill.

The cross-sectional comparison by Gaser and Schlaug demonstrated dose-dependent effects: professional musicians who had practiced intensively for years showed more extensive gray matter increases in motor, auditory, and visuospatial regions compared to amateur musicians, who in turn showed more than non-musicians. This gradient suggests that neuroplastic changes accumulate with practice amount—the more sustained and intensive the engagement, the more extensive the structural modifications.

Musical training isn’t about learning a new instrument every week. It requires focused development of technique, musical understanding, and performance skill on a specific instrument over months and years. The neuroplastic changes documented in research studies reflect this depth of engagement, not superficial exposure to varied musical experiences.

The Detraining Evidence

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for the necessity of sustained practice comes from detraining studies. The Draganski follow-up study examined what happened when juggling practice stopped after the initial three-month training period. The gray matter increases that had developed during training partially reversed over the subsequent three months without practice—declining by about 50% rather than returning fully to baseline.

This demonstrates that maintaining neuroplastic changes requires ongoing engagement—the brain reallocates resources away from skills that are no longer being used. Some structural consolidation persists even without practice, but full benefits require continued engagement. This finding has important implications for understanding neuroplasticity. The structural changes aren’t permanent stamps that remain regardless of continued practice. They represent dynamic adaptations that develop with sustained use and attenuate when use decreases.

This reinforces that meaningful neuroplastic change requires consistent, long-term engagement rather than brief exposure followed by abandonment in favor of the next new skill.

| Element | Poor Practice | Adequate Practice | Optimal Practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention | Distracted, multitasking | Focused on task | Deep focus with error monitoring |

| Challenge Level | Too easy (>90% success) | Moderate difficulty | 60-70% success rate (edge of ability) |

| Feedback | No feedback loop | Occasional self-assessment | Immediate feedback + adjustment |

| Progression | Same difficulty for weeks | Gradual increases | Systematic progressive overload |

| Consistency | 2-3x/week, irregular | 4-5x/week | 5-7x/week at same time |

The Optimal Practice Protocol Based on Research

The findings across neuroimaging studies allow us to extract specific principles for designing practice protocols that drive neuroplastic changes. While individual studies examined different skill domains with varying methodologies, several core principles appear consistently across the literature.

Choose Your Skill Domain Strategically

The research demonstrates that certain skill domains produce the most robust and well-documented neuroplastic changes. Motor skills, language learning, and musical training have the strongest evidence base, though this doesn’t mean other skills won’t produce changes—it simply means these domains have been most extensively studied with brain imaging technologies.

Motor skills offer several advantages for those seeking relatively rapid neuroplastic effects. The motor system is well-mapped neuroanatomically, making changes easier to detect and localize. Motor learning also provides immediate, tangible feedback about performance, which supports motivation and allows practitioners to track progress objectively. Studies show measurable changes can appear within 4-6 weeks for certain motor skills.

Language learning engages multiple brain systems simultaneously—phonological processing, semantic networks, grammatical analysis, working memory, and auditory-motor integration for speech production. This broad engagement produces changes across distributed brain regions and pathways. Language learning also has clear functional utility and provides numerous opportunities for practice and application in daily life.

Musical training combines motor, auditory, visual, and integrative cognitive demands, making it effective for producing broad neuroplastic effects. The temporal precision required for musical performance, the need to coordinate complex motor sequences with auditory feedback, and the interpretive and emotional aspects of musical expression engage diverse neural systems. Musical training produces some of the most extensive documented structural changes across multiple brain regions.

Commit to the 6+ Week Timeline with Domain-Specific Expectations

Based on the structural imaging studies, plan for at least six weeks of consistent practice as your minimum commitment, with clear understanding that most robust changes require 8-12 weeks or longer depending on skill domain and individual factors. The evidence shows considerable variability in timeline across different learning contexts.

Motor skills represent your fastest-results category. Taubert’s balance training study detected gray matter volume increases at six weeks. Karni’s motor sequence learning showed cortical expansion at 4-6 weeks. Even in the motor domain, the frequently-cited Draganski juggling studies required three months (12-13 weeks) to document their most robust gray matter changes. Think of six weeks as the earliest detection point for certain motor skills, not as a universal timeline or completion point.

Language learning typically requires longer investment. Mårtensson’s study detected structural changes at three months (12-13 weeks) in military interpreter trainees, but these participants were engaged in intensive, demanding full-time study programs. Schlegel’s intensive Chinese learning study examined changes over nine months. For language learning, realistic expectations should involve 8-12+ weeks of consistent practice before expecting measurable structural changes, with understanding that development continues over much longer timeframes as linguistic competence deepens.

Musical training shows the longest documented timelines. Hyde’s study detected changes at 15 months in children receiving keyboard lessons, though this doesn’t mean nothing happens earlier—it means the structural changes become measurable with current imaging technology after this extended practice period. The Gaser cross-sectional data suggests dose-dependent effects that accumulate progressively over years. For musical training, plan for a minimum 12-week commitment as your entry point, understanding that meaningful musical neuroplasticity extends well beyond the 6-week minimum—think of this domain as requiring 12+ weeks minimum, with changes continuing to develop over months to years.

The key principle is that ‘6+ weeks’ acknowledges this variability. The plus sign represents the reality that while some changes appear around six weeks in optimal conditions, most robust structural modifications require longer sustained engagement. Setting this expectation upfront prevents discouragement and supports the long-term commitment that neuroplasticity requires.

Practice Daily or Near-Daily with Sufficient Duration

While the studies don’t all specify exact frequency in identical ways, the successful protocols involved regular, frequent practice sessions. Taubert’s balance training participants practiced four times weekly—a near-daily schedule. The juggling studies involved daily practice expectations. Language learning protocols demanded daily study and engagement. Musical training combined weekly structured lessons with daily home practice.

The pattern suggests that 5-7 practice sessions per week represents optimal frequency for driving neuroplastic changes. This near-daily engagement provides the consistency and repetition the brain needs while allowing for rest and recovery that supports consolidation. Practice sessions should typically last 20-60 minutes depending on the skill and individual capacity, with intensity and focus prioritized over duration alone.

Daily practice serves several functions beyond simple repetition. It maintains activation of relevant neural circuits with minimal decay between sessions, supporting progressive strengthening rather than repeated relearning. It establishes consistent scheduling that becomes habitual, reducing motivation barriers. It provides sufficient practice volume for skill progression—the performance improvements that correlate with neural changes require substantial accumulated practice time.

‘Daily’ shouldn’t be interpreted as requiring perfect adherence. The research protocols generally involved structured programs over weeks to months, and occasional missed sessions don’t negate progress. The key factor is consistency over the full training period—maintaining engagement week after week—rather than perfectionist daily adherence that creates stress or leads to burnout and abandonment.

Maintain Deliberate, Focused Practice

The neuroplastic changes documented in research studies emerged from engaged, effortful practice, not passive exposure or mindless repetition. This distinction is key for understanding what kind of practice drives structural brain change.

Motor learning studies required attention to technique and gradual skill refinement. Participants weren’t simply going through motions—they were actively working to improve performance, attending to feedback, and adjusting movements based on errors. The Karni finger-tapping study specifically noted that participants had to maintain attention to sequence accuracy even as movements became more automatic. This attentional engagement appears necessary for driving cortical reorganization.

Language learning demanded active study, problem-solving, and application. The military interpreter trainees in Mårtensson’s study weren’t passively listening to language recordings—they were engaged in intensive coursework requiring vocabulary memorization, grammar analysis, translation practice, and active language production. The cognitive effort and active processing involved in these tasks appears necessary for driving the hippocampal and cortical changes observed.

Musical training involved focused practice on specific techniques, repertoire learning, and musical interpretation. The children in Hyde’s study received structured lessons with deliberate instruction plus home practice that required concentration and progressive skill development. This differs from casual playing—it involves systematic work on challenging material that requires sustained mental effort.

The concept of deliberate practice aligns well with what drives neuroplastic change. Deliberate practice involves focused attention on specific aspects of performance, immediate feedback about accuracy or quality, identification and correction of errors, and systematic progression to more challenging material as current skills are mastered. This active, engaged approach provides the conditions for neural circuit refinement and consolidation.

Ensure Progressive Challenge

The Dayan and Cohen review emphasizes that motor learning continues producing neuroplastic changes when skills become progressively more demanding. This principle likely extends across skill domains—neuroplasticity isn’t just about initial learning but about continued adaptation to increasing challenges.

Your practice protocol should include systematic increases in difficulty over time. As initial skills become more automatic and require less conscious attention, introduce variations, increased speed or precision demands, or more complex combinations. This progressive challenge maintains the effortful processing and attention that drives continued neural adaptation.

For motor skills, this might mean progressing from basic patterns to more complex sequences, increasing speed while maintaining accuracy, or adding environmental challenges that require greater adaptation. For language learning, it involves moving from vocabulary and basic grammar to more complex structures, authentic materials, and spontaneous conversation. For musical training, it means advancing to more technically demanding pieces, faster tempi, and more sophisticated interpretive challenges.

The brain appears to respond to novelty and challenge within a learned domain differently than to scattered exposure across unrelated domains. When you increase difficulty within your practiced skill, you’re building on established neural foundations rather than starting from scratch. This allows progressive refinement and expansion of existing circuits rather than superficial activation of new circuits without consolidation.

Practical Implementation—Three Evidence-Based Options

The following protocols translate the research findings into actionable practice frameworks. Each is based directly on successful neuroimaging studies and includes realistic timeline expectations based on the evidence.

Option 1: Motor Skill Learning (6-8 Weeks Minimum)

Motor skill practice produces the most rapid measurable neuroplastic changes documented in the literature, making it an accessible entry point for those seeking relatively quick results while building confidence in the process.

Evidence Foundation

This protocol draws from three key studies: Taubert’s balance training research, which showed gray matter changes at six weeks; Karni’s motor sequence learning study, which demonstrated cortical expansion at 4-6 weeks; and the Draganski juggling studies, which documented robust gray matter changes at three months with partial reversal when practice stopped.

Practical Protocol

Choose a motor skill that challenges coordination, requires sustained attention, and allows for objective performance measurement. Strong options include learning to juggle (directly following Draganski’s protocol), developing balance skills using slackline or balance board training (following Taubert’s approach), or mastering specific motor sequences through dance, martial arts forms, or sport-specific skills (following Karni’s approach).

Begin with clear baseline assessment of your current ability level. For juggling, this might be starting with two-ball exchanges. For balance training, measure how long you can maintain stability on your chosen apparatus. For movement sequences, assess accuracy and fluency at baseline speed.

Practice 20-40 minutes daily (or at minimum 4-5 times weekly) for at least 6-8 weeks. Structure each session with:

- Warm-up period focusing on basic movements and establishing concentration (5 minutes).

- Core practice working at the edge of your current ability, where success rate is about 60-70%—challenging enough to require effort but not so difficult that you experience constant failure (20-30 minutes).

- Deliberate attention to technique, error correction, and gradual refinement rather than mindless repetition.

- Cool-down period where you successfully execute easier variations to end on positive performance (5 minutes).

Track objective performance metrics weekly: number of successful juggling catches, balance duration, sequence accuracy percentage, or other measurable outcomes. This provides motivation through visible progress and confirms that underlying neural changes are occurring even before you feel subjectively different.

Expected Timeline and Milestones

- Weeks 1-2: Initial rapid improvement as your nervous system learns basic coordination patterns. Performance improvement driven primarily by fast learning processes rather than structural changes. Movements require high cognitive attention and feel effortful.

- Weeks 3-4: Performance improvement continues but may plateau temporarily as initial fast learning mechanisms saturate. Movements begin requiring less conscious attention for basic execution. This is when structural consolidation processes begin, though not yet detectable with imaging.

- Weeks 5-6: Based on Taubert and Karni’s findings, structural gray matter changes may be developing in motor-relevant regions around this timeframe. Subjectively, skills feel more automatic and robust. Performance becomes more consistent across practice sessions.

- Weeks 7-12: Continued structural consolidation with more robust and extensive changes, aligning with Draganski’s 3-month findings. Skills become increasingly automatic, requiring minimal conscious attention for execution. Performance improvements may continue as neural efficiency increases.

- Beyond 12 weeks: Consider either deepening expertise in your chosen skill by increasing difficulty (maintaining neuroplastic stimulus through progressive challenge) or transitioning to a new skill domain while maintaining your developed skill with reduced practice frequency (perhaps 2-3 times weekly) to prevent the reversal effects documented in the Draganski detraining study.

| Week | Duration | Focus | Success Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | 20 min/day, 6x/week | Two-ball exchanges, basic throws | 10 consecutive exchanges |

| 3-4 | 25 min/day, 6x/week | Three-ball cascade attempts | 5 consecutive catches |

| 5-6 | 30 min/day, 6x/week | Three-ball cascade refinement | 15-20 consecutive catches |

| 7-8 | 30-35 min/day, 5-6x/week | Pattern variations, endurance | 30+ consecutive catches |

Common Pitfalls and Solutions

- Pitfall: Starting too ambitiously with 60-minute daily practice sessions, leading to burnout within two weeks.

- Solution: Start with 15-20 minutes daily, building to 30-45 minutes over 2-3 weeks as practice becomes habitual.

- Pitfall: No objective tracking, making it hard to see progress and maintain motivation.

- Solution: Measure specific metrics weekly. For juggling, count consecutive catches. For balance, time stability duration. For sequences, calculate accuracy percentage.

- Pitfall: Giving up at 3-4 weeks when initial rapid gains plateau, right before structural changes begin.

- Solution: Commit to minimum 8 weeks upfront. Use a practice journal to document effort even when performance plateaus. Trust the research timeline.

Option 2: Language Learning (8-12+ Weeks Minimum)

Language learning produces robust neuroplastic changes across multiple brain systems and pathways, offering both cognitive benefits and practical functional utility.

Evidence Foundation

This protocol is based on Mårtensson’s military interpreter training study, which detected hippocampal and cortical changes at 3 months, and Schlegel’s intensive Chinese language learning research, which documented white matter structural changes over 9 months of study.

Practical Protocol

Commit to learning a new language using an immersive, intensive approach rather than casual dabbling. Select a language with personal relevance—either practical utility for travel or work, or strong personal interest that supports sustained motivation over months of study.

Dedicate 30-60 minutes daily to structured study incorporating multiple modalities and skill components:

- Vocabulary acquisition using spaced repetition systems that optimize memory consolidation (10-15 minutes daily). These systems present words at increasing intervals timed to just before forgetting would occur, maximizing retention efficiency.

- Grammar study and pattern analysis to understand the structural system of the language (10-15 minutes, can be reduced as patterns become internalized). This analytical component engages hippocampal and prefrontal systems involved in rule learning and pattern extraction.

- Listening comprehension using graded materials appropriate to your developing proficiency (10-15 minutes daily). Progress from simplified learning materials to increasingly authentic content. This trains phonological processing and auditory word recognition.

- Speaking practice, ideally with conversation partners via language exchange platforms or tutoring services (15-20 minutes, several times weekly minimum). Production practice is key for developing motor programs for speech articulation and for integrating comprehension with expression.

- Reading practice with texts at or slightly above your current level (10-15 minutes daily). Reading supports vocabulary expansion, grammatical pattern recognition, and written language processing pathways.

The key is combining these components into integrated study sessions that engage multiple language systems simultaneously. The military interpreter training studied by Mårtensson involved similarly intensive, multi-modal engagement—not passive listening or isolated vocabulary memorization.

Expected Timeline and Milestones

- Weeks 1-4: Rapid initial vocabulary acquisition and basic grammatical pattern learning. Performance improvements driven by explicit memory and conscious application of rules. Language processing feels highly effortful and requires full attention.

- Weeks 5-8: Continued vocabulary expansion with some items becoming more automatically accessible. Basic grammatical patterns begin feeling more intuitive and requiring less conscious analysis. Listening comprehension shows marked improvement as phonological processing adapts to new sound patterns.

- Weeks 9-12: Around this timeframe (matching Mårtensson’s 3-month detection point), structural changes in hippocampal and cortical regions may be developing. Subjectively, certain aspects of the language begin feeling more natural. You may experience moments of understanding without conscious translation. Speech production becomes somewhat less labored for practiced phrases and patterns.

- Weeks 13-24: Continued development of proficiency with progressive structural changes in language pathways. The white matter modifications in pathways like the arcuate fasciculus (documented by Schlegel at 9 months) support increasingly fluent connection between comprehension and production systems.

- Beyond 24 weeks: Language learning produces continuing neuroplastic changes over years of study and use. The initial 8-12 week commitment represents the minimum for detecting early structural changes, but language neuroplasticity continues developing as proficiency deepens.

| Week | Duration | Focus | Success Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-4 | 30-45 min/day, daily | Basic vocabulary (300-500 words), simple grammar, pronunciation | 500-word vocabulary, basic sentences |

| 5-8 | 45 min/day, daily | Grammar patterns, listening comprehension, speaking practice | Understand simple conversations, produce basic dialogue |

| 9-12 | 45-60 min/day, daily | Authentic materials, conversation practice, reading simple texts | Comprehend slow native speech, read basic texts |

Important Considerations

Language learning requires patience beyond the 6-week minimum mentioned in motor skill protocols. The ‘6+ weeks’ for language realistically means 8-12+ weeks before expecting measurable structural changes, with continued development over much longer timeframes. The complexity of language systems—phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics—means that comprehensive language knowledge takes extensive time to develop and consolidate neurally.

Intensive engagement is key. The successful protocols studied were demanding full-time programs (military interpreter training) or intensive coursework (Chinese study). Casual app-based study for 5-10 minutes daily, while better than nothing, likely won’t produce the robust changes documented in these studies. If you can only commit limited time, extend your timeline expectations proportionally.

Common Pitfalls and Solutions

- Pitfall: Focusing only on passive vocabulary study without speaking practice.

- Solution: Include speaking practice 3-4 times weekly minimum. Production practice drives different neural adaptations than comprehension alone.

- Pitfall: Using only one modality (like a single app) without varied engagement.

- Solution: Combine vocabulary work, grammar study, listening, speaking, and reading in each practice period. Multi-modal engagement produces broader neural changes.

- Pitfall: Expecting fluency after 8-12 weeks and becoming discouraged.

- Solution: Understand that 8-12 weeks marks when structural changes begin, not when fluency arrives. Set milestone expectations for basic proficiency, not native-like command.

Option 3: Musical Training (12+ Weeks Minimum)

Musical training produces the most extensive and widely-distributed neuroplastic changes documented in the research literature, affecting motor, auditory, visual, and integrative brain systems.

Evidence Foundation

This protocol is based on Hyde’s study of children receiving keyboard lessons over 15 months, and the Gaser and Schlaug cross-sectional comparison showing dose-dependent structural differences between professional musicians, amateur musicians, and non-musicians.

Practical Protocol

Begin formal musical instruction on an instrument of your choice. While Hyde’s study examined keyboard training, the principles likely apply across instruments that require motor-auditory coordination. Choose an instrument that genuinely interests you, as sustained motivation over months is necessary.

Combine structured weekly lessons with daily home practice:

- Weekly lessons (30-60 minutes) with a qualified instructor who provides systematic technical instruction, repertoire assignments, and performance feedback. The structured instruction component is key—it provides expert modeling, error correction, and progressive curriculum that self-teaching often lacks.

- Daily home practice (30-45 minutes minimum, ideally 5-7 days weekly) that includes:

- Technical exercises (scales, arpeggios, technique-specific drills) that develop motor control and auditory discrimination (10-15 minutes). These might feel mechanical but they build necessary neural-motor programs.

- Repertoire practice working on assigned pieces at various stages of development (20-30 minutes). Include some pieces within your comfort zone for consolidation and confidence, plus more challenging pieces that require problem-solving and progressive skill development.

- Musical interpretation and expression work, not just mechanical note-reading. This engages emotional and interpretive processing, connecting motor execution with musical meaning.

- Attention to listening while playing—monitoring tone quality, rhythm accuracy, dynamic control. This auditory-motor integration is central to musical neuroplasticity.

Track practice time and maintain a practice log noting specific work done, difficulties encountered, and progress observed. This supports motivation and ensures systematic coverage of necessary skill components rather than only playing enjoyable material.

Expected Timeline and Milestones

- Weeks 1-6: Initial motor learning of basic technical patterns and note reading. Steep learning curve with rapid visible progress. Movements feel highly conscious and effortful. Coordination between hands (for keyboard) or between motor actions and sound production (all instruments) requires intense concentration.

- Weeks 7-12: Technical basics become more consolidated, requiring less conscious attention. You begin playing simple pieces with some musical flow rather than purely mechanical note-by-note execution. Reading becomes somewhat more fluent. This period establishes foundations upon which structural changes will build.

- Weeks 13-24: Continued technical development with expanding repertoire complexity. Around this timeframe, some structural changes may be developing in motor and auditory regions, though Hyde’s study detected changes at 15 months, suggesting longer timelines for robust structural modifications. Subjectively, the instrument begins feeling more natural and intuitive. Musical expression becomes possible, not just mechanical reproduction.

- Weeks 25-52: Progressive structural changes continue developing across motor cortex, auditory cortex, and corpus callosum regions (connecting left and right brain hemispheres for bilateral coordination). The Gaser cross-sectional data suggests these changes accumulate with practice amount over years.

- Beyond one year: Musical training produces some of the most extensive documented neuroplastic changes, but these develop over years of sustained practice. The initial 12-week commitment represents an entry point and minimum for beginning to establish neural changes. Realistic expectations should acknowledge that musical expertise develops over years, not weeks, with neuroplastic changes continuing to accumulate throughout this development.

| Week | Practice Structure | Focus | Success Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-4 | Weekly lesson + 20-30 min daily | Hand position, basic scales, simple melodies | Play C major scale, simple songs with both hands |

| 5-8 | Weekly lesson + 30 min daily | Technique drills, reading practice, easy repertoire | Read basic notation fluently, play 3-4 simple pieces |

| 9-12 | Weekly lesson + 35-40 min daily | Expanding scales, early intermediate pieces, musicality | Multiple scales, play with basic dynamics and phrasing |

| 13-16 | Weekly lesson + 40-45 min daily | Intermediate technique, expressive playing, performance prep | Perform 2-3 pieces with musical interpretation |

Important Considerations

Musical training represents the longest timeline among the evidence-based options. While motor skills may show changes around 6 weeks and language learning around 8-12 weeks, musical neuroplasticity typically requires 12+ weeks minimum, with most robust changes developing over months to years. This doesn’t mean musical training is inferior—it reflects the complexity and extent of neural systems engaged and modified.

The dose-dependent relationship observed in cross-sectional studies suggests that continued practice produces continuing neuroplastic development. Professional musicians with decades of intensive practice show more extensive structural differences than amateurs who practice less intensively. This indicates that neuroplasticity in the musical domain is progressive and cumulative over very long timeframes.

Practice quality matters enormously. Mindless repetition of the same simple pieces won’t drive the progressive neuroplastic changes documented in research. You need systematic technical development, progressively challenging repertoire, and focused attention to musical execution—the kind of engaged, deliberate practice that structured lessons support.

Common Pitfalls and Solutions

- Pitfall: Attempting to self-teach without structured instruction or curriculum.

- Solution: Invest in weekly lessons with a qualified instructor. Structured instruction with expert feedback is necessary for developing proper technique and avoiding bad habits.

- Pitfall: Only practicing pieces you already know well, avoiding challenging new material.

- Solution: Always work on at least one piece at the edge of your ability. Progressive challenge drives continued neural adaptation.

- Pitfall: Practicing mechanically without listening to tone quality or musical expression.

- Solution: Record yourself weekly. Listen back critically. Focus on producing beautiful sound, not just hitting correct notes.

Building Your Personal Neuroplasticity Plan

The neuroscience research provides clear guidance that challenges popular assumptions while offering an evidence-based framework for boosting brain plasticity.

The Core Principle: Depth Over Breadth

The most important takeaway from the neuroimaging literature is that effective neuroplasticity requires sustained engagement with specific skills over weeks to months, not scattered exposure to numerous different activities. The ‘learn something new every day’ approach, while potentially beneficial for general cognitive stimulation and psychological variety, doesn’t align with the protocols that produce measurable structural brain changes in research settings.

This doesn’t mean you’re limited to practicing only one skill for your entire life. Rather, it means that meaningful neuroplastic development requires sequential depth: committing fully to developing specific skills over appropriate timeframes (6+ weeks minimum, often longer) before potentially transitioning to new domains.

Managing Expectations About Timelines

The ‘6+ weeks’ timeframe mentioned in the research should be understood as a minimum for the earliest detectable changes in optimal conditions (typically motor skills), not as a universal timeline or completion point. Most robust structural changes require 8-12+ weeks or longer, depending on skill domain complexity.

This extended timeline might initially seem discouraging compared to popular ’21 days to change your brain’ claims, but it’s actually encouraging news. The changes documented in research studies are real, measurable, and functionally significant—they’re not placebo effects or wishful thinking. When you commit to evidence-based practice protocols over appropriate timeframes, you’re engaging the same processes that neuroscientists have directly visualized with brain imaging technology.

The Question of Multiple Skills

Individual studies focused on single skills for methodological clarity and to isolate specific neural changes, but this doesn’t mean your personal neuroplasticity strategy must involve only one skill indefinitely. The key is avoiding simultaneous pursuit of multiple demanding skills without sufficient practice depth in any.

Consider a sequential approach: commit to intensive practice of one skill domain for 8-12+ weeks (or longer for complex domains like language or music), then transition to a new domain while maintaining your developed skill with reduced practice frequency. The Draganski detraining study showed that changes partially reversed when practice stopped completely, but maintaining developed skills with reduced frequency (perhaps 2-3 practice sessions weekly) likely preserves at least some structural modifications while allowing focus on new skill development.

Alternatively, you might deeply develop one primary skill over months while engaging in a secondary skill at lower intensity. For example, intensive language learning as your primary neuroplastic focus (30-60 minutes daily) while maintaining existing musical skills with weekly practice. The key factor is ensuring at least one skill receives the sustained, intensive engagement required for robust neuroplastic development.

Beyond Initial Learning: Progressive Challenge

Neuroplasticity doesn’t stop once you’ve completed 6-12 weeks of practice. The research, particularly the Dayan and Cohen review of motor learning, emphasizes that continued neuroplastic adaptation occurs when skills become progressively more challenging. This suggests that long-term neuroplasticity strategy should involve not just initial skill acquisition but ongoing skill development.

As practiced skills become more automatic and require less effortful processing, introduce systematic increases in difficulty. This maintains the challenge and attentional engagement that drives continued neural adaptation. For motor skills, increase speed, precision, or complexity. For language learning, progress from structured study to authentic immersive use. For musical training, advance to more technically and interpretively demanding repertoire.

This approach to progressive challenge differs from abandoning developed skills to constantly pursue new ones. You’re building on established neural foundations, deepening and expanding existing circuits rather than superficially activating new circuits without consolidation.

Individual Variation and Personalization

The studies cited examined group averages across participants. Individual variation means some people may show neuroplastic changes somewhat faster or slower than group averages suggest. Factors including age, prior experience in related domains, genetic variability, sleep quality, overall health, and practice quality all influence the rate and extent of neuroplastic development.

This individual variation doesn’t negate the core principles—sustained, focused practice over weeks to months drives measurable changes—but it does mean your personal timeline might differ from study averages. The key is maintaining consistent engagement long enough for your brain to develop and consolidate structural changes, regardless of whether that matches study averages exactly.

Younger individuals generally show faster and more extensive neuroplastic changes, but the research includes adult participants across age ranges, demonstrating that neuroplasticity persists throughout life even if somewhat reduced with aging. The Hyde music study examined children, but the Draganski juggling studies, Mårtensson language research, and Schlegel language learning all involved adults, confirming that adult brains remain capable of experience-dependent structural modification.

Scaling Beyond One Skill—Long-Term Development

While individual studies focus on specific skills over defined periods, a comprehensive personal neuroplasticity strategy can incorporate multiple domains and extend over years. The key is structuring this long-term development according to principles that the research supports.

Sequential Depth: The Quarterly Approach

One practical framework involves organizing skill development into quarterly cycles. Commit fully to one skill domain for 12 weeks (3 months), providing sufficient time for robust neuroplastic changes to develop even in complex domains. After completing this cycle, assess whether to continue deepening that skill or transition to a new domain while maintaining the developed skill at reduced intensity.

This quarterly structure aligns well with the research timelines. Twelve weeks exceeds the 6-week minimum for motor skills, matches the detection point for language and juggling changes, and provides a substantial foundation for musical development. It’s long enough for meaningful structural changes while being psychologically manageable as a defined commitment period.

A year-long plan might involve: Quarter 1 (January-March) intensive motor skill development establishing your fastest neuroplastic changes and building confidence in the process; Quarter 2 (April-June) transition to language learning while maintaining motor skill with reduced practice; Quarter 3 (July-September) continue language learning or transition to musical training; Quarter 4 (October-December) ongoing development in chosen domains with progressive challenge.

This framework provides structure without rigidity. You can adjust based on personal progress, interests, and circumstances. The key principle is maintaining depth of engagement within each period rather than superficially sampling many skills simultaneously.

Cross-Domain Transfer and Integration

While the studies examined specific skills in isolation, some evidence suggests that neuroplastic changes in one domain may support learning in related areas. Motor learning might help subsequent learning of different motor skills. Language learning in one language may support subsequent learning of additional languages. Musical training develops auditory discrimination that might transfer to other auditory processing tasks.

These transfer effects, while not as well-documented as domain-specific changes, suggest potential benefits from strategic sequencing of skill development. Starting with motor skills (fastest results) might build general learning capacity and confidence that supports tackling more complex domains later. Language learning might boost attention and memory systems that benefit subsequent skill learning in other domains.

Transfer effects shouldn’t be overstated. The neuroplastic changes documented in research are largely specific to practiced skills and the neural systems they engage. You won’t develop language processing improvements by practicing juggling, or motor skill boosts from studying vocabulary. The value of cross-domain development comes from comprehensively engaging diverse brain systems over time, not from expecting broad transfer from specific skill practice.

Maintenance vs. Development: Balancing Established and New Skills

The Draganski detraining study revealed that neuroplastic changes partially reversed when juggling practice stopped completely. This raises important questions about maintaining developed skills while pursuing new domains.

The research doesn’t definitively answer what minimal practice frequency maintains neuroplastic changes without full developmental levels of intensity. A reasonable hypothesis based on the findings is that established skills can be maintained with reduced practice frequency—perhaps 2-3 sessions weekly instead of daily practice—while directing intensive developmental practice toward new skills.

This approach allows expanding your skill portfolio over years without requiring ever-increasing practice time. After establishing a motor skill with 6-8 weeks of intensive daily practice, reduce to 2-3 maintenance sessions weekly while beginning intensive practice in a language domain. After developing language skills over 8-12+ weeks, maintain both skills at reduced frequency while beginning musical training.

The key distinction is between developmental practice (intensive, frequent, focused on progressive improvement) and maintenance practice (reduced frequency, focused on preserving established abilities). This allows long-term accumulation of diverse skills and broad neuroplastic development across multiple brain systems.

Progressive Challenge Within Domains

Long-term neuroplasticity development involves not just maintaining skills but continuing to deepen them through progressive challenge. The motor learning literature particularly emphasizes that neuroplastic adaptation continues when task demands increase systematically.

For motor skills, this might mean progressing from basic juggling patterns to more complex variations, or from basic balance challenges to increasingly difficult dynamic balance tasks. For language learning, progress from structured study to authentic immersive use, native-level media consumption, and sophisticated written expression. For musical training, advance through increasingly technically and interpretively demanding repertoire.

This progressive challenge approach maintains neuroplastic stimulus over long timeframes. Rather than the brain reaching a stable state after initial learning, continuing challenges drive ongoing adaptation and refinement. This aligns with the cross-sectional findings from the Gaser musical expertise study, which showed dose-dependent effects—more extensive practice over years produced more extensive structural changes.

Lifelong Learning as Neuroplasticity Strategy

The research supports viewing neuroplasticity not as a short-term intervention but as a lifelong approach to learning and skill development. Rather than seeking quick fixes or minimal-effort ‘brain training,’ the evidence points toward sustained engagement with meaningful skill development as the most effective neuroplasticity strategy.

This reframing aligns neuroplasticity with broader goals of lifelong learning, personal development, and mastery pursuit. The neuroplastic changes become a beneficial consequence of meaningful skill development rather than an isolated goal pursued through artificial exercises.

This perspective also addresses motivation challenges. Sustaining practice over months requires intrinsic interest and perceived value beyond just ‘brain health.’ Choosing skills with genuine personal relevance—languages you’ll use, instruments you want to play, motor skills that support activities you enjoy—increases likelihood of maintaining the sustained engagement that neuroplasticity requires.

Measuring Your Progress Without a Brain Scanner

Readers implementing these protocols won’t have access to MRI scanners to visualize their neuroplastic changes, but several practical indicators can serve as proxies for the structural and functional brain modifications documented in research studies.

Objective Skill Performance Metrics

All the neuroimaging studies correlated brain changes with measurable skill improvement. Participants who showed greater structural or functional neural modifications also demonstrated superior skill performance. This means that tracking objective performance measures provides indirect evidence that underlying neuroplastic changes are occurring.

For motor skills, establish clear, quantifiable performance metrics from the outset. If learning to juggle, track the number of consecutive catches you can maintain. If practicing balance, measure the duration you can sustain stability or the difficulty level of challenges you can successfully handle. If mastering movement sequences, assess accuracy percentage and execution speed.

Record these metrics weekly using consistent testing procedures. Progressive improvement over weeks provides strong indirect evidence that your brain is developing and consolidating the neural circuits supporting the skill. The performance improvements don’t happen magically—they reflect the underlying neural changes that imaging studies have visualized.

For language learning, track vocabulary size using spaced repetition system statistics, assess comprehension speed with timed reading exercises, record fluency in speaking tasks, and measure accuracy in translation or written production. These objective measures correlate with the neural changes in language pathways and hippocampal regions documented in the Mårtensson and Schlegel studies.

For musical training, track technical proficiency through scale speeds and accuracy, repertoire advancement through pieces mastered, and performance quality through recording self-assessments or instructor feedback. These metrics reflect the motor, auditory, and integrative neural changes developing across brain regions documented in the Hyde and Gaser studies.

Subjective Effort and Automaticity Shifts

The motor learning research demonstrates that skills initially requiring high cognitive effort and conscious attention progressively become more automatic as neural circuits consolidate. This subjective experience of effort reduction provides another proxy for underlying neuroplastic changes.

Pay attention to how effortful your practiced skill feels across weeks of practice. Initially, new skills demand intense concentration—you must consciously think about every component of the action. As neural circuits develop and consolidate, the same performance requires progressively less conscious attention. Actions that initially demanded your full cognitive resources become more fluid, automatic, and require minimal conscious monitoring.

This automaticity shift correlates with the neural efficiency changes documented in fMRI studies. As circuits consolidate, they require less widespread activation and operate more efficiently. Subjectively, this manifests as the skill feeling more natural, intuitive, and automatic rather than effortful and deliberate.

Document this progression periodically. After 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 6 weeks, and 8+ weeks, reflect on and record how effortful the skill feels compared to initial practice. Descriptions like ‘requires constant conscious attention,’ ‘becoming more fluid with occasional automatic segments,’ ‘largely automatic with conscious attention needed only for challenging aspects,’ ‘feels natural and intuitive’ capture this progression.

Free Tools for Tracking Progress

Motor Skills

- Video recording: Use your smartphone to record weekly practice sessions. Compare form, speed, and smoothness across weeks. Visual documentation reveals progress that feels subtle day-to-day.

- Simple stopwatch apps: Track duration metrics for balance or endurance-based skills. Many free timer apps allow you to log and graph results over time.

- Rep counters: For skills like juggling, use tally counter apps to record consecutive successful repetitions. Some apps can export data for tracking trends.

Language Learning

- Anki or similar spaced repetition software: These apps provide built-in statistics showing vocabulary retention curves, review accuracy, and learning velocity. The data reveals consolidation patterns.

- Free reading speed tests: Online tools can measure words-per-minute in your target language. Monthly testing shows comprehension speed improvements.

- Voice recording apps: Record yourself speaking or reading aloud weekly. Listen back to track pronunciation accuracy and fluency development over weeks.

Musical Training

- Metronome apps with tempo tracking: Many free metronome apps let you save tempo settings for different pieces. Document the tempo at which you can play accurately, tracking speed increases over weeks.

- Recording apps: Use your smartphone to record practice sessions or specific pieces monthly. Comparison recordings reveal tone quality, accuracy, and musicality improvements.

- Practice log templates: Download or create simple spreadsheets to log daily practice time, focus areas, and difficulties encountered. Pattern recognition helps optimize practice efficiency.

Transfer and Generalization Effects

Some research suggests that neuroplastic changes in one domain may help learning in related areas, though these transfer effects are typically more modest than domain-specific improvements. If you notice that skills related to your primary practice area become easier to acquire or improve faster than expected, this may indicate broader neural changes beyond the specific practiced task.

For example, after intensive balance training, you might notice improved performance in other activities requiring postural control or vestibular processing. After language learning, you might find general improvements in auditory processing, working memory, or attention control. After musical training, you might observe better auditory discrimination or motor sequencing in other contexts.

These transfer effects shouldn’t be overstated or expected, but their presence can provide additional evidence that neuroplastic changes are developing. Document any unexpected improvements in related skills or cognitive functions during your primary skill practice period.

Stability and Retention of Improvements

The Draganski detraining study demonstrated that when practice stops, neuroplastic changes partially reverse over subsequent months. Conversely, when improvements persist even with reduced practice frequency, this suggests underlying structural consolidation has occurred.

After your initial intensive practice period (6-12+ weeks depending on skill domain), reduce practice frequency to 2-3 times weekly for several weeks. If your performance remains stable or continues improving despite reduced practice intensity, this indicates that structural changes have consolidated sufficiently to maintain the skill with less frequent reinforcement.

This stability test provides practical confirmation that neuroplastic changes have developed. Skills supported only by temporary functional adaptations without structural consolidation typically show rapid decay when practice frequency decreases. Skills supported by consolidated structural changes show greater persistence.

Confidence and Perceived Competence

While subjective and psychological rather than direct neural measures, your self-assessed confidence and sense of competence in the practiced skill reflect cumulative learning and consolidation. Progressive increases in confidence across weeks of practice correlate with the underlying neural changes supporting improved performance.

Track your subjective confidence ratings weekly using a simple scale. ‘How confident do you feel in your ability to successfully perform this skill?’ rated 1-10 provides a simple metric. Progressive increases over weeks indicate that your brain has sufficiently consolidated the skill to support reliable, consistent performance—a functional outcome of neuroplastic changes.

Similarly, assess your sense of whether the skill feels like ‘part of you’ versus something you’re awkwardly attempting. As neural circuits consolidate, skills progressively feel more natural and integrated into your motor or cognitive repertoire. This subjective sense of skill ownership reflects the depth of neural consolidation.

Consistency Across Contexts and Conditions

Initial skill learning often produces performance that’s highly context-dependent—you can execute the skill under specific, optimal conditions but performance degrades with any variation. As neuroplastic consolidation progresses, skills become more robust and work across varied contexts.

For motor skills, test performance under different conditions: different times of day, when fatigued versus fresh, in different environments, with distractions present. Progressive ability to maintain performance across varied conditions indicates robust neural consolidation rather than fragile context-specific learning.

For language skills, assess whether comprehension and production work not just with familiar practice materials but with novel authentic content, in spontaneous conversation, under time pressure, or with unfamiliar accents or dialects. Increasing robustness across varied contexts indicates deep processing and consolidated neural changes.

The Combination Provides Evidence

No single proxy perfectly indicates neuroplastic change, but the combination of objective performance improvement, subjective automaticity shifts, transfer effects, retention stability, growing confidence, and cross-context consistency provides strong evidence that underlying neural changes are occurring. When multiple indicators show progressive improvement over weeks of consistent practice, you can be reasonably confident that the neuroplastic processes documented in research studies are unfolding in your brain, even without direct imaging confirmation.

Troubleshooting Guide—When Progress Stalls