You’ve been lied to about learning. Schools told you that some people are “just smart” while others have to work harder. They said intelligence is fixed. That you either get it or you don’t. Science says otherwise.

Your brain isn’t a hard drive with limited storage. It’s more like a muscle that gets stronger with the right training. The difference between fast learners and slow learners isn’t IQ. It’s strategy.

Fast learning happens when your brain encodes information quickly AND stores it long-term. Think of it like this: cramming for a test is like shoving clothes into a closet. You might pass the exam, but everything falls out the next day. Real learning is like folding clothes and putting them in labeled drawers. It takes more effort up front, but you’ll find what you need years later.

This article breaks down 12 techniques backed by peer-reviewed research. These aren’t productivity hacks or study tips from some self-help guru. These are methods tested in labs, proven in meta-analyses, and supported by over 1,500 experiments.

Quick Reference: Choose Your Learning Techniques

| Technique | Best For | Time Investment | Difficulty Level | Results Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spaced Repetition | Memorization, facts, vocabulary | Medium | Easy | 1-4 weeks |

| Retrieval Practice | Test preparation, recall | Low | Medium | Immediate |

| Interleaving | Problem-solving, discrimination | Medium | Hard | 2-6 weeks |

| Elaboration | Deep understanding, concepts | Medium | Medium | 1-2 weeks |

| Desirable Difficulty | Mastery, expertise | High | Hard | 4-12 weeks |

| Focused Attention | All learning types | Low | Easy | Immediate |

| Sleep Consolidation | Memory, integration | Medium | Easy | 1 night |

| Aerobic Exercise | Brain health, focus | Medium | Easy | 2-12 weeks |

| Error-Driven Learning | Skill acquisition | Low | Medium | Immediate |

| Chunking | Complex information | Low | Medium | 1-3 days |

| Dual Coding | Visual learners, complex systems | Medium | Easy | Immediate |

| Short Breaks | Sustained focus | Low | Easy | Immediate |

The 12 Pillars of Accelerated Learning

1. Spaced Repetition: The End of Cramming

Your brain forgets information on a curve. After you learn something new, you lose about 50% of it within an hour. By tomorrow, you’ve lost 70%. This is called the Forgetting Curve.

Spaced repetition fights this curve by reviewing information right before you’re about to forget it. A 2006 meta-analysis by Cepeda and colleagues examined 839 assessments across 317 experiments. The verdict? Spacing out your study sessions beats cramming every single time.

Here’s what’s wild: the same amount of study time produces dramatically different results depending on when you schedule it. Three one-hour sessions spread over a week will give you better retention than three hours in one night.

The science: Your brain needs time to transfer information from short-term to long-term storage. This process happens during rest periods between study sessions. When you cram, you’re trying to force everything through a narrow door all at once. When you space it out, you give each piece of information time to settle.

Your Spaced Repetition Schedule

| Review # | Time After Learning | What To Do | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Review | 1 day | Quick recall test, fix errors | 5-10 min |

| 2nd Review | 3 days | Active retrieval, no notes | 10-15 min |

| 3rd Review | 1 week | Full practice test | 15-20 min |

| 4th Review | 2 weeks | Mixed with new material | 10 min |

| 5th Review | 1 month | Quick check for retention | 5 min |

| 6th Review | 3 months | Long-term maintenance | 5 min |

Pro tip: If something feels too easy during review, skip to the next interval. If you struggle, add an extra review between the current and next interval.

How to use it: Review new material within 24 hours. Then again after 3 days. Then after a week. Then after a month. Each review should be quick—just enough to reactivate the memory. Apps like Anki automate this process, but you can also use a simple calendar reminder system.

The key is fighting the urge to review too soon. If something feels too easy when you review it, you’re wasting your time. Wait until it feels slightly difficult to recall.

2. Retrieval Practice: The Power of the Test

Rereading your notes feels productive. It’s comfortable. You recognize the information and think, “Yeah, I know this.”

But recognition isn’t the same as recall.

Roediger and Karpicke proved this in a 2006 study. They split students into two groups. One group studied a passage four times. The other group studied it once, then took three practice tests. A week later, the testing group recalled 50% more information.

Think about that. Less studying, more testing, better results.

Study Method Comparison: What The Research Shows

| Study Method | 1 Week Retention | 1 Month Retention | Study Time Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rereading notes 4x | 35% | 18% | Low (wasted repetition) |

| Highlighting + rereading | 40% | 22% | Very low (false confidence) |

| Study 1x + test 3x | 68% | 56% | High (less time, better results) |

| Spaced testing | 78% | 67% | Very high (optimal retention) |

| Combined techniques* | 85%+ | 75%+ | Extremely high |

*Combined: Spaced repetition + retrieval practice + elaboration

The science: When you retrieve information from memory, you strengthen the neural pathways to that information. It’s like walking through tall grass. The first time is hard. But each time you walk the same path, it gets easier. Testing forces you to walk that path.

Rereading is like looking at a map of the path. Sure, you see it. But you’re not building the muscle memory to walk it yourself.

How to use it: Close your notes and write down everything you remember. Don’t peek. Struggle with it. Use flashcards, but make sure you’re generating the answer before flipping the card. Take practice quizzes. Explain concepts out loud without looking at your materials.

The discomfort you feel when trying to recall something? That’s growth. Your brain is working to reconstruct the information, and that work makes the memory stronger.

3. Interleaving: Mixing It Up for Mastery

Most people practice in blocks. If you’re learning math, you do 20 addition problems, then 20 subtraction problems, then 20 multiplication problems.

This feels efficient. You get into a rhythm. You feel like you’re making progress.

But blocked practice creates an illusion. You’re not actually learning to recognize which type of problem you’re facing. You’re just repeating a pattern.

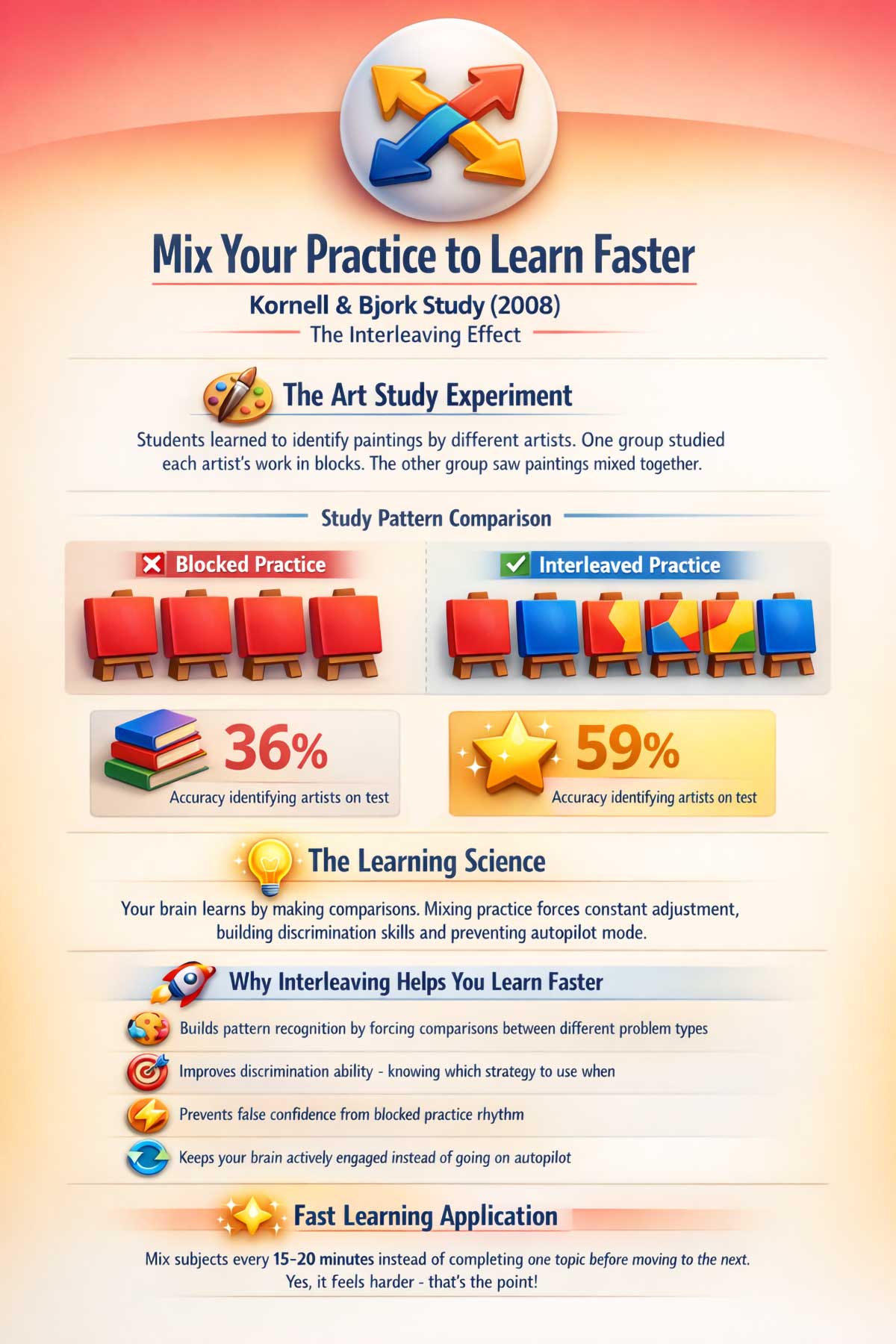

Kornell and Bjork tested this in 2008 with art students. One group studied paintings by each artist in blocks. The other group saw the paintings mixed up. During the test, the interleaved group identified artists correctly 59% of the time. The blocked group? Just 36%.

The science: Your brain learns by making comparisons. When you practice different skills in the same session, you’re forcing your brain to constantly adjust. This builds discrimination—the ability to recognize what type of problem you’re facing and choose the right solution.

It also prevents your brain from going on autopilot. Each new problem requires fresh attention.

Sample Interleaving Schedule (90-Minute Study Session)

| Time Block | Subject A | Subject B | Subject C |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-15 min | Math: Algebra problems | – | – |

| 15-30 min | – | History: Essay outline | – |

| 30-45 min | – | – | Biology: Diagram labeling |

| 45-60 min | Math: Geometry problems | – | – |

| 60-75 min | – | History: Timeline practice | – |

| 75-90 min | – | – | Biology: Practice quiz |

Why this works: Your brain never settles into autopilot. Each switch requires fresh attention and problem identification.

How to use it: Mix up your practice. If you’re learning languages, alternate between vocabulary, grammar, and listening in the same session. If you’re studying chemistry, shuffle problem types instead of doing all stoichiometry problems together.

Yes, this feels harder. That’s the point. The difficulty during practice translates to better performance when it actually counts.

4. Elaboration: The Self-Explanation Strategy

Passive reading is the enemy of learning. Your eyes can move across a page while your brain does nothing.

Active learning requires you to explain the material to yourself. Not just what the information is, but WHY it’s true and HOW it connects to what you already know.

Chi and colleagues studied this in 1994. They tracked students learning physics. The high explainers—students who constantly asked themselves “why does this work?”—built correct mental models of the concepts. Many low explainers never got there.

The science: Your brain stores information in networks. New information needs to connect to existing knowledge. When you explain something, you’re building those connections manually. You’re forcing your brain to integrate the new information into what you already understand.

This is why teaching is such a powerful learning tool. When you teach, you have to organize your knowledge, find the core principles, and translate them into simple language. All of that work strengthens your own understanding.

The 5-Question Self-Explanation Framework

Ask yourself these after every study section:

| Question Type | Example Questions | What It Builds |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | What exactly does this mean? Can I define it in my own words? | Basic understanding |

| Mechanism | How does this work? What’s the process? | Functional knowledge |

| Connection | How does this relate to [previous concept]? Where have I seen this before? | Integration |

| Application | When would I use this? What problems does this solve? | Transfer |

| Prediction | What would happen if we changed [variable]? What are the limits? | Deep mastery |

How to use it: After reading a section, close the book. Ask yourself: Why is this true? How does it work? What would happen if we changed one variable? How does this relate to something I learned last week?

Better yet, try the “explain it to a child” method. If you can’t explain a concept in simple terms, you don’t actually understand it. The gaps in your explanation show you exactly what you need to study more.

5. Desirable Difficulty: Embracing the Struggle

Here’s a paradox: learning that feels easy during practice often leads to poor retention. Learning that feels hard during practice often leads to better long-term mastery.

This is called desirable difficulty, a concept developed by Robert and Elizabeth Bjork.

Think about lifting weights. If you lift something light, it feels easy. But you’re not building muscle. To grow stronger, you need resistance. Your brain works the same way.

The science: When something feels easy, your brain doesn’t need to work hard to process it. You might feel confident, but you’re building what the Bjorks call “fluency”—the feeling of knowing something without actually having deep mastery.

Difficult practice forces your brain to reconstruct information, make connections, and solve problems. This cognitive work is what builds long-term retention.

How to use it: Avoid rereading highlights or notes until they feel familiar. That familiarity is a trap. Instead, test yourself on material you’ve barely reviewed. Try to solve problems before you’ve seen the solution method. Study without your notes, even if it means struggling.

The key is choosing the RIGHT kind of difficulty. Difficulty is only desirable if you can eventually figure it out. If something is so hard that you make no progress, you need to back up and build more foundation first.

6. Focused Attention: The High Cost of Context Switching

Your brain can’t multitask. Period.

What you think of as multitasking is actually rapid task-switching. And every switch has a cost.

Ophir and colleagues studied heavy multitaskers in 2009. They found these people were actually WORSE at filtering out irrelevant information. They had reduced working memory control. Their attention was scattered.

The science: When you switch from one task to another, your brain needs time to disengage from the first task and reload the context for the second task. This “switching penalty” can cost you up to 40% of your productive time.

Worse, divided attention during learning means information doesn’t encode properly. If you’re half-listening to a lecture while checking your phone, neither activity gets your full processing power. The information goes in shallow and comes out fuzzy.

Deep Work Environment Checklist

Before Your Study Session:

| Category | Action Items | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Digital |

|

Each notification costs 25 min of focus recovery |

| Physical |

|

Environmental clutter = mental clutter |

| Auditory |

|

Unexpected sounds break concentration |

| Temporal |

|

Open-ended sessions lead to drift |

How to use it: Create a deep work environment. Turn off notifications. Close unnecessary tabs. Put your phone in another room. Set a timer for focused work blocks.

Even small distractions break your concentration. An email notification might only take 5 seconds to dismiss, but it can take 25 minutes to get back into deep focus.

Batch your shallow tasks—email, messages, admin work—into dedicated time blocks. Protect your learning time like it’s sacred. Because it is.

7. Sleep-Based Consolidation: Learning While You Dream

Sleep isn’t just rest. It’s when your brain does some of its most important work.

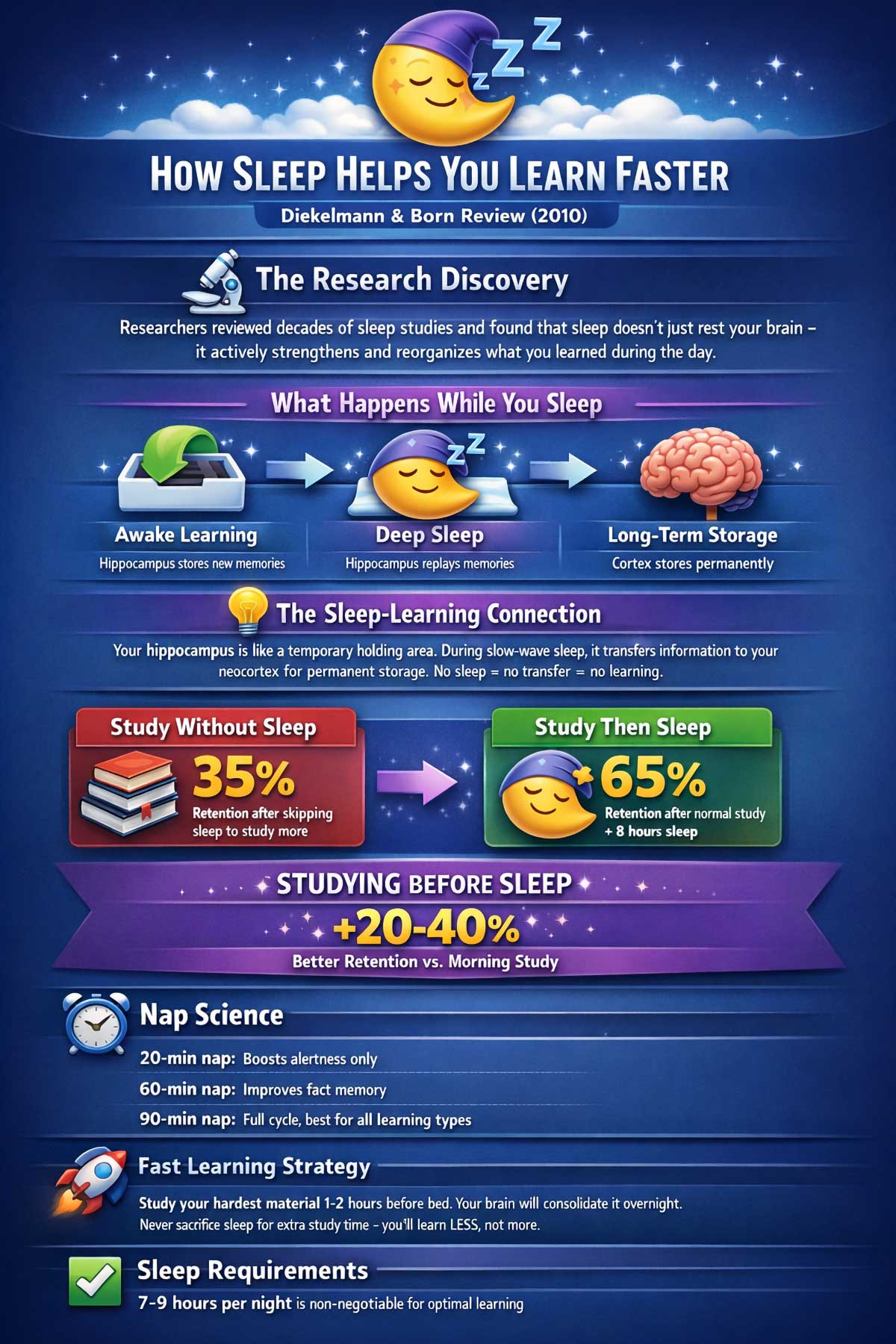

Diekelmann and Born reviewed the research in 2010. They found that sleep actively strengthens and reorganizes newly learned information. During slow-wave sleep, your hippocampus replays the day’s experiences and transfers them to your neocortex for long-term storage.

The science: Your hippocampus is like a temporary holding area for new memories. It can only hold so much. During sleep, particularly during deep slow-wave sleep, your brain transfers information from this temporary storage to permanent storage in your cortex.

This process also integrates new information with existing knowledge. Your brain finds patterns, makes connections, and solves problems while you sleep. This is why people often wake up with solutions to problems they couldn’t solve the day before.

Sleep-Learning Optimization Protocol

| Study Type | Best Study Time | Sleep Duration Needed | Why This Works |

|---|---|---|---|

| New vocabulary/facts | 8-9 PM | 7-9 hours | Slow-wave sleep consolidates declarative memory |

| Motor skills (instrument, sport) | 6-7 PM | 7-9 hours | REM sleep strengthens procedural memory |

| Problem-solving | 7-8 PM | 8+ hours | Sleep integrates solutions across memory networks |

| High-volume cramming | Avoid! | N/A | Information doesn’t consolidate without sleep |

The Nap Protocol:

- 20-minute nap: Boosts alertness, doesn’t enter deep sleep

- 60-minute nap: Improves declarative memory (facts, names)

- 90-minute nap: Full sleep cycle, improves both declarative and procedural memory

Best nap timing: 1-3 PM (aligns with natural circadian dip)

How to use it: Study before sleep. Your brain will consolidate what you learned overnight. If you have a big learning session, don’t stay up late. The sleep you’re sacrificing is when the actual learning happens.

Naps work too. A 90-minute nap after a heavy study session can boost retention. The key is getting into deep sleep, which typically happens in naps longer than 60 minutes.

Don’t sacrifice sleep for study time. It’s a bad trade. One night of good sleep after moderate studying beats an all-nighter every time.

8. Aerobic Exercise: Growing Your Brain’s Hardware

Exercise doesn’t just make your body stronger. It makes your brain bigger.

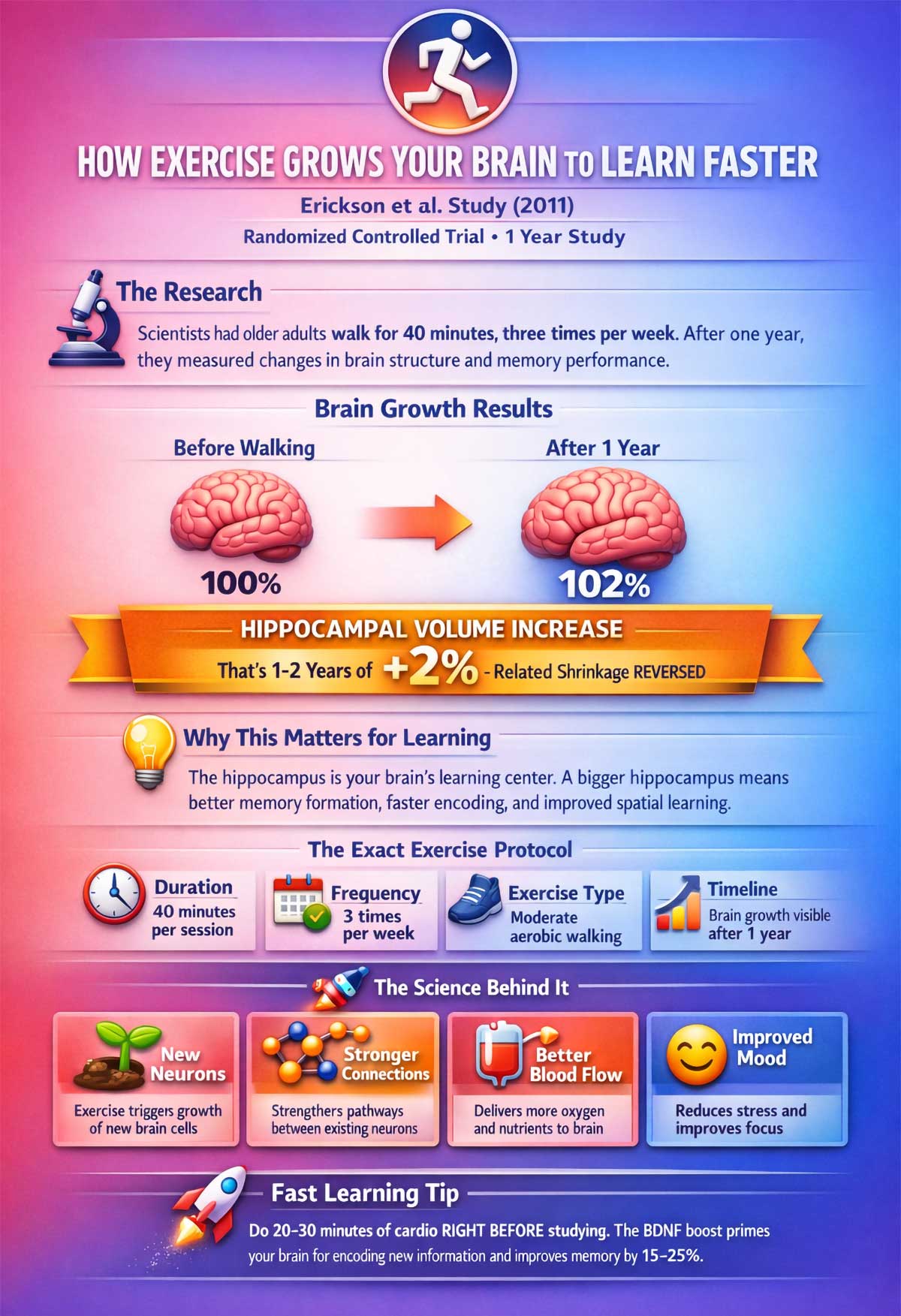

Erickson and colleagues ran a randomized controlled trial in 2011. They had older adults walk for 40 minutes three times per week. After one year, their hippocampal volume increased by 2%. That reversed 1-2 years of age-related shrinkage and improved spatial memory.

Think about that. Walking literally grew their brains.

The science: Aerobic exercise increases levels of BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor). This protein acts like fertilizer for your brain cells. It promotes the growth of new neurons and strengthens connections between existing ones.

Exercise also increases blood flow to the brain, delivering more oxygen and nutrients. It reduces inflammation. It improves mood and reduces stress, both of which help with learning.

Exercise Timing for Maximum Learning Benefit

| Exercise Type | Duration | Best Timing | Learning Benefit | When You’ll Feel It |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light walk | 10-15 min | Right before studying | 15-20% focus boost | Immediate |

| Moderate cardio | 20-30 min | Morning before learning | BDNF elevation lasts 2-3 hours | 10-60 min after |

| HIIT workout | 15-20 min | 2-3 hours before studying | Peak BDNF levels | 1-2 hours after |

| Long run/bike | 45-60 min | Separate day from intense studying | Hippocampal growth | 4-12 weeks |

Quick Movement Breaks During Study:

- 30 jumping jacks

- 2 minutes of stairs

- 5 minutes of yoga stretches

- Walk around the block

Research shows: Even 10 minutes of movement improves memory encoding by 15-25%.

How to use it: Take short movement breaks during study sessions. A 10-minute walk can boost your focus and memory. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) appears to be particularly effective for BDNF release.

You don’t need to become a marathon runner. Moderate aerobic exercise—anything that gets your heart rate up—produces benefits. Even standing up and doing jumping jacks for a minute can help.

The best time to exercise? Right before a learning session. The BDNF boost primes your brain for encoding new information.

9. Error-Driven Learning: The Mistake Advantage

Getting something wrong isn’t failure. It’s a learning tool.

Metcalfe reviewed the research in 2017 and found that making errors during learning—especially when you’re confident in your wrong answer—improves retention more than passive study.

This seems backwards. Shouldn’t you avoid mistakes? Wouldn’t wrong information contaminate your learning?

No. Your brain learns best when it’s surprised.

The science: When you make a confident error and then discover you’re wrong, your brain pays extra attention to the correction. This surprise creates a stronger memory trace than if you’d just read the correct information passively.

Think of errors as red flags for your brain. They highlight areas where your understanding is incomplete. Your brain prioritizes fixing these gaps.

The Pre-Testing Protocol (Use Errors Strategically)

| Step | Action | Time | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Read the question/problem | 30 sec | Prime your brain |

| 2 | Make your best guess (write it down) | 1-2 min | Create prediction |

| 3 | Rate your confidence (1-10) | 5 sec | Track metacognition |

| 4 | Check the correct answer | 30 sec | Create surprise moment |

| 5 | Write why you were wrong | 1-2 min | Build correction memory |

| 6 | Re-attempt the problem immediately | 2 min | Strengthen correct pathway |

Why high-confidence errors matter: When you’re sure you’re right but you’re wrong, your brain creates a “surprise flag” that makes the correction stick 3x better than low-confidence errors.

How to use it: Before studying new material, try to guess the answer. Even if you have no idea, make your best guess. When you’re wrong, you’ll remember the correct answer better.

Use practice tests and quizzes frequently. Don’t wait until you feel ready. Test yourself early and often, even when you know you’ll make mistakes. Each error is a chance to strengthen the correct information.

The key is getting immediate feedback. If you make an error but don’t find out for a week, the benefit is lost. Test yourself, check your answer right away, and study the correction.

10. Chunking: Optimizing Your Mental RAM

Your working memory can hold about 4-7 pieces of information at once. That’s not much.

But here’s the trick: you get to decide what counts as “one piece.”

Gobet and colleagues reviewed chunking research in 2001. They found that experts don’t have better memory than beginners. They just organize information into bigger chunks.

The science: A chess master doesn’t remember individual piece positions. They recognize patterns—”this is a French Defense opening” or “this is a common endgame position.” Each pattern is one chunk, even though it contains dozens of individual pieces.

Your brain naturally looks for patterns. Chunking is the deliberate process of organizing information into meaningful groups. This dramatically increases what you can hold in working memory and how quickly you can process it.

Chunking in Action: Before and After

| Learning Task | Without Chunking (7 items) | With Chunking (3-4 items) |

|---|---|---|

| Phone Number | 5-5-5-1-2-3-4 (7 digits) | 555-1234 (2 chunks) |

| Historical Dates | 1776, 1789, 1812, 1848, 1865, 1914, 1945 (7 dates) | American Revolution Era (1776, 1789) 19th Century Conflicts (1812, 1848, 1865) World Wars (1914, 1945) |

| Vocabulary | Dog, cat, oak, pine, rose, tulip, daisy (7 words) | Animals (dog, cat) Trees (oak, pine) Flowers (rose, tulip, daisy) |

| Chemistry | H, He, Li, Be, B, C, N (7 elements) | Period 1 (H, He) Period 2 Light (Li, Be, B) Period 2 Life (C, N) |

The Pattern: Don’t memorize individual items. Find the structure that groups them logically.

How to use it: Look for patterns in what you’re learning. Group related items together. Create acronyms or phrases to bundle information. Find the underlying structure.

If you’re learning a list of items, group them by category. If you’re learning a process, break it into stages. If you’re learning vocabulary, group words by root or theme.

The more meaningful the chunks, the better. Random grouping helps a little. Logical grouping based on actual relationships helps a lot.

11. Dual Coding: The Visual-Verbal Connection

Your brain has two separate systems for processing information: one for words and one for images. Most people only use one.

That’s a waste.

Paivio developed dual coding theory in 1991, and Mayer expanded it in 2009. The basic idea: when you combine verbal and visual information, you create two memory traces instead of one. This makes recall easier and more reliable.

The science: Verbal and visual information are processed in different parts of your brain. When you encode the same information both ways, you create multiple retrieval paths. If you forget the verbal explanation, you might still remember the picture. And vice versa.

This is why diagrams, charts, and illustrations are so powerful. They’re not just decoration. They’re a second encoding of the information.

Dual Coding Strategies by Subject

| Subject | Verbal Approach | Visual Approach | Combined Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| History | Timeline of events, cause-effect chains | Draw timeline with icons/symbols, mind map of relationships | See chronology AND connections |

| Science | Write out process steps, definitions | Diagram the process with arrows, sketch the system | Understand flow AND structure |

| Math | Write formula, explain what each variable means | Graph the equation, draw geometric representation | Know formula AND its meaning |

| Languages | Write vocabulary with translations | Draw simple picture representing the word | Word AND mental image |

| Literature | Character descriptions, plot summary | Character relationship map, plot diagram | Details AND story structure |

Simple Visual Techniques (No Artistic Skill Required):

- Boxes and arrows for processes

- Circles and lines for relationships

- Simple stick figures for people/actions

- Color coding for categories

- Spatial arrangement (top/bottom, left/right) for hierarchy

How to use it: When you study text, draw simple diagrams. They don’t need to be artistic. A basic sketch of how a process works or how concepts relate is enough.

When you look at diagrams, explain them in words. Write captions. Talk through what the image shows.

Create concept maps that show relationships between ideas. Use different colors for different categories. Add small icons or symbols to represent key concepts.

The physical act of drawing also helps. It forces you to slow down and think about the relationships between concepts. And the visual you create becomes another memory cue.

12. Frequent Short Breaks: The Vigilance Restoration

Your brain can’t maintain peak focus indefinitely. After about 50 minutes of sustained attention, your performance drops.

Ariga and Lleras tested this in 2011. They had participants do a repetitive task for 50 minutes. The group that took brief mental breaks maintained their performance. The group that worked straight through showed significant declines.

The science: Sustained attention depletes cognitive resources. Your brain needs breaks to restore vigilance. These breaks don’t need to be long—even micro-breaks of 30 seconds can help.

The key is disengagement. Switching to a different mental task doesn’t count as a break. Checking email or scrolling social media doesn’t restore attention. True breaks involve either physical movement or complete mental rest.

Break Activities: What Works vs. What Doesn’t

| Break Type | Duration | Good Activities | Bad Activities | Recovery Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-break | 30-60 sec | Close eyes, deep breath, look at distance | Check phone, read email | Low but frequent |

| Short break | 5 min | Stretch, walk, get water, bathroom | Social media, news, texts | Medium |

| Medium break | 10-15 min | Walk outside, light snack, chat with friend | YouTube, shopping, gaming | High |

| Long break | 30-60 min | Exercise, meal, nap, hobby | Netflix, deep work on different subject | Very high |

The Recovery Rule: True breaks involve either movement or complete mental rest. Switching tasks doesn’t count as a break.

Optimal Pattern for 4-Hour Study Block:

- 50 min work → 10 min break

- 50 min work → 10 min break

- 50 min work → 30 min break

- 50 min work → Done for the session

How to use it: Use a timer to remind yourself to take breaks. Work for 50 minutes, break for 10. Or try shorter cycles: 25 minutes of work, 5 minutes of break.

During breaks, move around. Look out a window. Close your eyes. Do some stretches. The goal is to let your mind wander and your focused attention system rest.

Don’t skip breaks to “power through.” Your brain’s performance will drop, and you’ll end up wasting time staring at material you’re not actually processing. Regular breaks maintain high-quality focus throughout your entire study session.

Technique Stacking: Combining Methods for Maximum Impact

The Power Combos

| Combo Name | Techniques Combined | Best For | Expected Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Memory Master | Spaced Rep + Retrieval + Sleep | Memorization, exams | 3-4x better retention |

| The Deep Learner | Elaboration + Desirable Difficulty + Dual Coding | Conceptual mastery | 2-3x better understanding |

| The Fast Starter | Exercise + Focus + Short Breaks | Quick learning sessions | 50% more productivity |

| The Skill Builder | Interleaving + Error-Driven + Chunking | Problem-solving, skills | 2x faster skill acquisition |

| The Complete System | All 12 techniques | Professional mastery | 5-10x overall improvement |

Beginner Stack (Start Here)

Week 1-2: Add these three

- Focused Attention (eliminate distractions)

- Short Breaks (every 25-50 minutes)

- Sleep (7-9 hours consistently)

Week 3-4: Add these three 4. Retrieval Practice (test yourself daily) 5. Spaced Repetition (schedule reviews) 6. Exercise (20 min before studying)

Week 5-8: Add the rest 7-12. Interleaving, Elaboration, Desirable Difficulty, Error-Driven, Chunking, Dual Coding

Why this order? Foundation first (attention, breaks, sleep), then core learning methods (testing, spacing), then advanced techniques.

The Accelerated Learning Weekly Protocol

Standard Protocol (10-15 hours/week)

Monday: Learn + Exercise

Start the week with new material. Do a 20-minute exercise session first to boost BDNF levels. Then spend 90 minutes on focused learning. Use dual coding—take notes AND draw diagrams. Break every 25 minutes.

End the session with retrieval practice. Close your notes and write down what you remember.

Tuesday: Interleave + Review

Mix topics from Monday with something new. Spend 60 minutes alternating between subjects every 15 minutes. This feels harder than blocked practice, but that’s the point.

Before bed, do a quick review of Monday’s material. Just 10 minutes. This is your first spaced repetition.

Wednesday: Deep Work + Nap

Pick your hardest topic. Spend 2 hours in deep focus with no interruptions. Embrace the difficulty. Struggle with problems before looking at solutions.

Take a 90-minute nap after this session. Your brain will consolidate what you learned.

Thursday: Test Yourself

No new material today. Instead, take practice tests on everything you’ve learned this week. Use retrieval practice heavily. Make errors and correct them immediately.

Pay special attention to topics where you made confident mistakes. Your brain will flag these for extra processing.

Friday: Exercise + Light Review

Start with 30 minutes of aerobic exercise. Then do a light review of the week’s material using spaced repetition. This is your 3-day review for Tuesday’s content and 4-day review for Monday’s.

Focus on material that feels difficult to recall. Skip anything that comes back easily.

Weekend: Chunking + Elaboration

Take time to see the big picture. How do this week’s topics connect? What patterns can you find? Create concept maps. Explain topics out loud as if teaching someone.

This elaboration work strengthens your mental models and helps with long-term retention.

Sleep: 7-9 Hours Every Night

Non-negotiable. Sleep is when your brain transfers information from temporary to permanent storage. Sacrificing sleep for study time is like watering a plant but cutting its roots.

Weekly Protocol Overview

| Day | Focus | Techniques Used | Session Length | Energy Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mon | New learning | Exercise, Dual Coding, Breaks | 90 min | High |

| Tue | Mixed practice | Interleaving, Spaced Rep | 60 min | Medium |

| Wed | Deep work | Desirable Difficulty, Focus, Nap | 2 hours + 90 min nap | Very High |

| Thu | Testing | Retrieval Practice, Error-Driven | 90 min | Medium |

| Fri | Light review | Exercise, Spaced Rep | 60 min | Low |

| Sat | Integration | Chunking, Elaboration | 2 hours | Medium |

| Sun | Rest/light review | Sleep Consolidation | 30 min optional | Very Low |

Intensity Levels (Customize Based on Goals)

| Intensity | Weekly Hours | Best For | Techniques Emphasized |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light | 5-7 hours | Maintenance, hobby learning | Spaced Rep, Short Breaks, Sleep |

| Moderate | 10-15 hours | Professional development, certification | All 12 techniques, balanced |

| Intensive | 20-25 hours | Exam prep, career transition | Retrieval Practice, Interleaving, Exercise |

| Extreme | 30+ hours | Medical school, bar exam | All techniques + professional guidance |

Applying These Techniques by Subject

For Language Learning

| Technique | How To Apply | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Spaced Rep | Review vocabulary at increasing intervals | Day 1, 3, 7, 14, 30 |

| Retrieval | Cover English, recall foreign word | Quiz yourself without looking |

| Interleaving | Mix grammar, vocab, listening in one session | 15 min each, rotate |

| Dual Coding | Draw pictures for vocabulary words | Sketch “dog” with the word “perro” |

| Error-Driven | Speak/write before checking correctness | Try the sentence, then verify |

For Mathematics

| Technique | How To Apply | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Interleaving | Mix problem types (algebra, geometry, calc) | Don’t do 20 derivative problems in a row |

| Retrieval | Solve problems without looking at examples | Close the textbook, try from memory |

| Elaboration | Explain why a method works | “We factor because…” |

| Chunking | Recognize problem patterns | “This is a quadratic in disguise” |

| Error-Driven | Attempt problems before seeing solutions | Struggle first, then check |

For Test Preparation (Medical, Bar, CPA, etc.)

| Technique | How To Apply | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Spaced Rep | Review each topic multiple times over months | USMLE: review systems every 2 weeks |

| Retrieval | Practice questions > reading review books | Do 50+ questions daily |

| Interleaving | Mix subjects rather than completing one first | Don’t finish all cardio before starting renal |

| Desirable Difficulty | Use harder question banks | UWorld over easier resources |

| Sleep | Never sacrifice sleep for extra study | 8 hours non-negotiable |

Common Learning Mistakes (And How To Fix Them)

| Mistake | Why It Fails | The Fix | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highlighting everything | Creates false familiarity, no active processing | Use retrieval practice instead | 3x better retention |

| Studying one subject all day | No interleaving, mental fatigue | Switch subjects every 45-60 min | 2x better discrimination |

| Cramming before exams | No time for consolidation | Start 2-3 weeks early with spaced practice | 4x better performance |

| Listening to lectures passively | No elaboration or encoding | Take notes, ask questions, explain concepts | 2-3x better understanding |

| Rereading notes until familiar | Fluency illusion | Test yourself when it still feels hard | 50% better long-term retention |

| Studying tired | Poor encoding, wasted time | Exercise first or reschedule after rest | 2x more efficient |

| Multitasking while studying | Divided attention, shallow processing | Single-task with focus environment | 40% time savings |

| Reviewing too early | Not desirable difficulty | Wait until recall feels slightly difficult | Better consolidation |

| Skipping sleep to study more | Blocks consolidation | Protect sleep, study smarter not longer | Information actually sticks |

| Avoiding difficult material | No error-driven learning | Start with hard problems, learn from mistakes | Faster skill development |

Track Your Progress: Learning Metrics That Matter

| Metric | How To Measure | Good Baseline | Target Goal | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retention Rate | Score on practice test 1 week later | 30-40% | 70-80% | 4-8 weeks |

| Study Efficiency | Hours needed to master topic | Varies | 30-50% reduction | 6-12 weeks |

| Focus Duration | Minutes of uninterrupted work | 15-25 min | 50-90 min | 3-6 weeks |

| Retrieval Speed | Time to recall key concepts | Slow, effortful | Quick, automatic | 8-12 weeks |

| Application Ability | Can solve new problems with concepts? | 20-30% | 70-80% | 8-16 weeks |

| Confidence Accuracy | Your confidence matches actual performance | Often mismatched | Well-calibrated | 6-12 weeks |

Weekly Self-Assessment Questions:

- Can I recall this week’s material without notes? (Test it)

- Can I explain concepts to someone else clearly?

- Can I apply these concepts to new problems?

- How many hours did I study vs. how much did I learn?

- Which techniques am I actually using vs. just reading about?

Learning Audit Checklist

Use this checklist to evaluate your current habits. Each “no” is an opportunity for improvement.

Each technique you’re missing is probably cutting your learning efficiency by 10-30%. Add them one at a time over the next few weeks.

From Hard Work to Smart Work

You don’t need to work harder. You need to work smarter.

The difference between struggling learners and fast learners isn’t talent or IQ. It’s strategy. The techniques in this article aren’t magic. They’re just applied neuroscience.

Your brain is built to learn. It’s been doing it since you were born. These 12 techniques simply remove the obstacles and optimize the process.

Start with one or two techniques. Spaced repetition and retrieval practice give you the most bang for your buck. Once those feel natural, add interleaving. Then elaboration. Build the system piece by piece.

The goal isn’t to use all 12 techniques all the time. The goal is to understand how your brain works and give it what it needs to learn efficiently.

Your Next Steps (Do This Today)

- Choose your starting trio: Focus, Breaks, and Sleep (easiest wins)

- Set up your spaced repetition schedule for current learning material

- Take one practice test on material you “know” (test your assumptions)

- Block 90 minutes on your calendar for focused study tomorrow

- Download one tool (Anki for spaced rep or Forest for focus)

The 30-Day Challenge

Week 1: Master the foundation (Focus, Breaks, Sleep)

- Zero phone during study

- 25-50 min work blocks

- 8 hours sleep nightly

Week 2: Add active learning (Retrieval, Spaced Rep)

- Test yourself daily

- Schedule first reviews

Week 3: Increase difficulty (Interleaving, Elaboration)

- Mix subjects

- Explain concepts out loud

Week 4: Complete system (remaining techniques)

- Add exercise before study

- Use dual coding

- Embrace difficult practice

Track your retention rate at day 1, 14, and 30. Most people see 2-3x improvement.

Stop cramming. Stop rereading. Stop pretending that time spent equals knowledge gained.

Start spacing. Start testing. Start struggling with difficult material.

FAQs

What is the fastest way to learn something new?

Combine spaced repetition with retrieval practice. Test yourself at increasing intervals (1 day, 3 days, 1 week) rather than rereading material. Research shows this improves retention by 50-200%.

How can I improve my memory and learning ability?

Focus on three areas: (1) Test yourself regularly instead of rereading, (2) Space your study sessions over days and weeks, and (3) Get 7-9 hours of sleep after learning. These three changes alone can triple your retention.

Does exercise really help you learn faster?

Yes. Aerobic exercise increases BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), which promotes neuron growth. Studies show 20-30 minutes of cardio before studying can improve focus and memory encoding by 15-25%.

How long should study breaks be?

Take 5-10 minute breaks after every 25-50 minutes of focused work. During breaks, move around or rest your mind completely. Avoid checking phone or email, as this doesn’t restore attention.

What is the most effective study technique?

Retrieval practice (testing yourself) combined with spaced repetition. This combination outperforms all other single techniques, improving long-term retention by 3-4x compared to rereading notes.

How many hours a day should I study?

Quality matters more than quantity. 2-3 hours of focused, technique-based study (with breaks) beats 6-8 hours of passive rereading. Use the techniques in this article to maximize efficiency.

Can you learn while sleeping?

Not exactly. You can’t learn new information while asleep, but sleep consolidates what you learned while awake. Studying before sleep improves retention by 20-40% compared to studying in the morning without sleep afterward.

What time of day is best for studying?

This varies by person, but generally: (1) Exercise before studying to boost BDNF, (2) Study new material when you’re most alert, (3) Review material before sleep for consolidation. Match study intensity to your energy levels.

Why do I forget everything I study?

You’re likely rereading instead of testing yourself, and you’re not spacing your reviews. Switch to retrieval practice (close your notes and recall information) and schedule reviews at 1 day, 3 days, 1 week, and 1 month after learning.

How do I stay focused while studying?

Create a distraction-free environment. Put your phone in another room, close all browser tabs except what you need, and work in 25-50 minute blocks with breaks. Each notification or distraction costs you up to 25 minutes of focus recovery time.

Is highlighting and rereading effective for studying?

No. Highlighting creates a false sense of familiarity but doesn’t improve retention. Research shows rereading your notes four times produces only 35% retention after one week. Testing yourself produces 68% retention with less time invested.

How long does it take to see results from these techniques?

Some techniques (retrieval practice, focused attention, breaks) show immediate benefits. Others (spaced repetition, exercise effects on brain volume) take 2-12 weeks. Most people see noticeable improvement in retention within 2-4 weeks of consistent application.