When you’re trying to lose weight, the scale feels like the only thing that matters. The number goes down, and it feels like progress. But two people can both lose 20 pounds and end up with completely different bodies — one leaner and more metabolically healthy, the other softer and more prone to regaining the weight. Researchers at Tel Aviv University published a study in January 2026 that makes a compelling case for looking beyond the number — and it changes how we should think about fat loss entirely.

The study, led by Prof. Yftach Gepner along with Yair Lahav and Roi Yavetz, compared how three different exercise approaches affected body composition during a low-calorie diet. The results were striking. Not every pound lost is the same. And for people who want to lose fat without sacrificing the muscle that keeps their metabolism running, strength training stands in a category of its own.

The Weight Loss Showdown: 304 Adults, Three Approaches

The Lahav, Yavetz & Gepner study, published in Frontiers in Endocrinology, analyzed data from 304 adults — 183 men and 121 women — aged 20 to 74, with BMIs ranging from 18.5 to 45 kg/m². All participants followed a calorie-restricted diet designed to create roughly a 500-calorie daily deficit. Every participant received the same protein target: 1.5 grams per kilogram of body weight per day, guided by a registered dietitian.

The difference between groups was exercise choice. Participants self-selected one of three approaches:

- No exercise (NO): Diet only. Cut calories, let the body do the rest.

- Aerobic exercise (AR): 150 to 250 minutes of cardio per week, combined with the diet.

- Resistance training (RT): Two to three strength training sessions per week, combined with the diet.

The average follow-up period was 5.1 months. Progress was tracked using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) — a low-dose X-ray scan that distinguishes between bone, lean tissue, and fat mass with precision that scales, calipers, and standard impedance devices can’t match.

Total weight loss across all three groups was similar. On the surface, every approach worked. But when researchers looked at what each group actually lost, the story became far more interesting.

The Scale’s Blind Spot: When Weight Loss Doesn’t Mean Fat Loss

Here’s the problem with tracking only body weight: the number doesn’t tell you what you lost. Muscle and fat both register on a scale. Losing muscle when you’re trying to lose fat isn’t just unhelpful — it actively works against you.

In the Lahav et al. study, the no-exercise group lost a meaningful amount of lean mass alongside fat. The aerobic exercise group did better, but they still lost fat-free mass over the program. Both outcomes follow a well-documented pattern: when you cut calories without a specific signal to preserve muscle, the body treats lean tissue as fair game for energy. Research has long suggested that roughly 25% of weight lost during caloric restriction alone comes from lean mass — not fat.

The resistance training group was the exception. They lost more fat than either of the other groups. And they were the only group to actually increase their fat-free mass — gaining lean tissue while in a caloric deficit.

The researchers captured this with a metric they called the fat-mass-to-weight-loss ratio — essentially, how much of the total weight lost came from fat versus lean tissue. The RT group had the highest ratio by a clear margin. That difference was statistically significant (p = 0.0002 vs. no exercise; p = 0.0051 vs. aerobic).

In men, the RT group lost an average of 8.9 kg of fat mass, compared to 7.8 kg in the aerobic group and 5.8 kg in the no-exercise group — despite similar total weight loss across all three. Women showed the same pattern. A ratio above 1.0 in the RT group — meaning fat loss exceeded total scale weight lost — is only possible because lean mass actually increased at the same time.

This is what the researchers describe as “quality” weight loss. Their own framing: reducing fat mass while preserving lean mass, rather than simply shrinking the number on the scale.

Why Strength Training Changes Body Composition

Resistance training sends a direct signal to your body: these muscles are being used. When you lift weights or push against load, that signal is strong enough to tell your body to hold onto lean tissue — even when calories are restricted.

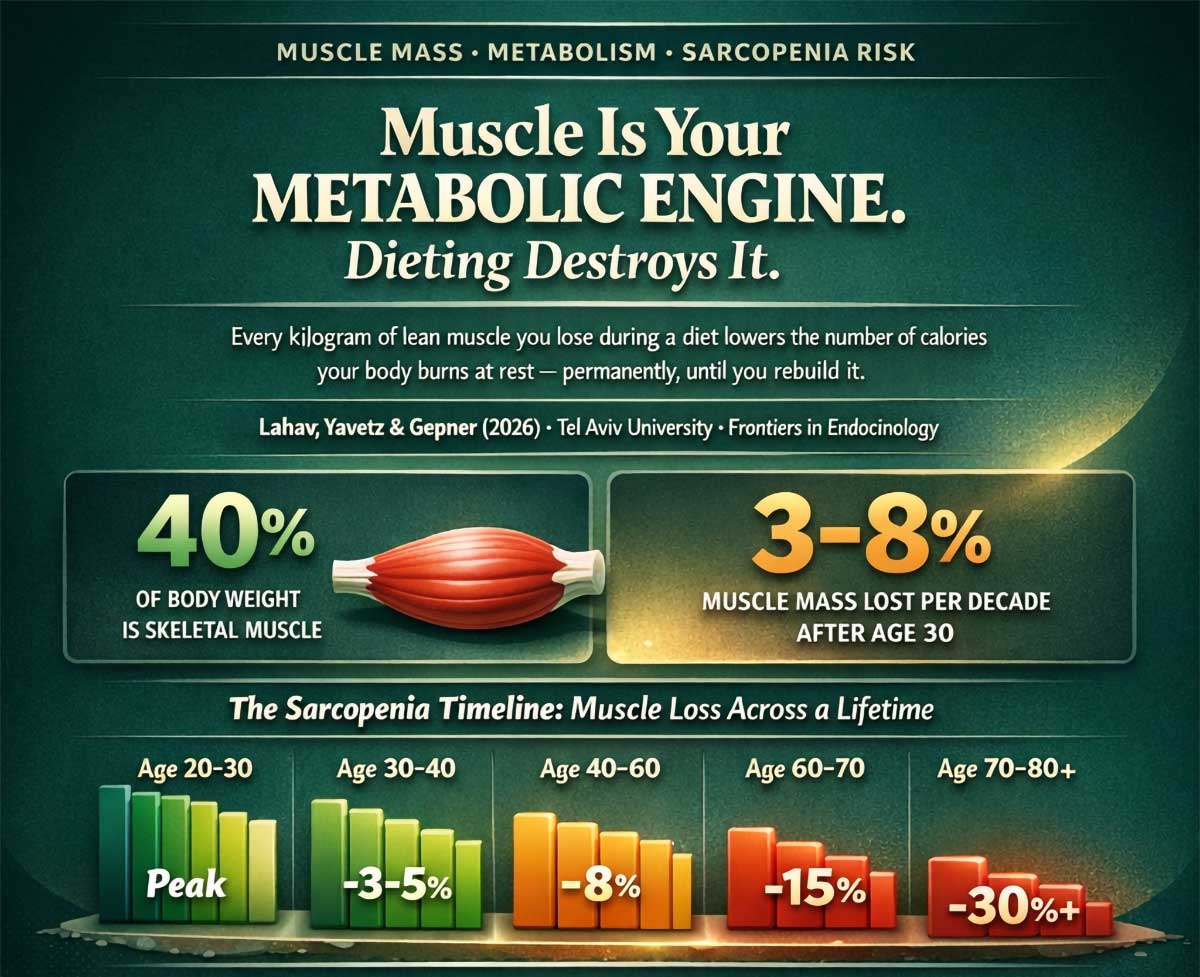

Muscle is a metabolic engine. It burns fuel even while you’re sitting still. The more you have, the higher your resting calorie burn. Strip it away through dieting, and that engine shrinks. Your metabolism slows. Future weight gain becomes more likely. Weight loss that costs you muscle works against your long-term goals, even when the scale says otherwise.

Strength training interrupts this pattern. Instead of letting the caloric deficit pull energy from both fat and muscle, resistance work sends a “keep this” signal to lean tissue. The body is pushed to draw its energy more selectively from fat stores. The result is a much more favorable split — and a body that is leaner in proportion, not just lighter in total weight.

The Lahav et al. study showed this clearly and consistently. Across both men and women, RT was the only exercise modality associated with an increase in fat-free mass during weight loss. The no-exercise group lost 2.8 kg of lean mass in men and 2.94 kg in women. The aerobic group lost 1.1 kg in men and 0.37 kg in women. The resistance training group gained lean mass in both sexes: +0.8 kg in men and +0.9 kg in women.

The Waistline: A Better Marker Than the Scale

One of the more practical findings in the study involved waist circumference — a measure that tells you more about metabolic risk than total body weight does.

Abdominal fat, particularly the kind that accumulates around the organs, is strongly linked to cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. Waist circumference is one of the most reliable ways to track this fat without expensive imaging. The researchers included it as a marker of weight loss quality, measuring it at the level of the navel.

Across all groups, waist circumference declined. But the resistance training and aerobic groups both showed larger reductions than the no-exercise group. The RT group averaged a reduction of 9.0 cm in men, compared to 8.0 cm in the aerobic group and 6.1 cm in the no-exercise group.

More striking was the correlation between waist reduction and fat mass loss: r = 0.84, p = 0.0001. Put simply, the more fat someone lost, the more their waist shrank — and the two tracked each other so consistently that the researchers validated waist circumference as a reliable practical marker of fat-focused weight loss.

If you’re tracking your progress, this is worth noting. A shrinking waist — even when the scale barely moves — often signals that the right kind of weight is being lost.

Sarcopenia: The Hidden Cost of Losing Muscle While Dieting

There’s a longer-term consequence to losing muscle during weight loss that doesn’t get enough attention.

Sarcopenia is the progressive loss of muscle mass and strength. It’s typically associated with aging — muscle mass naturally declines by roughly 3 to 8% per decade after age 30, accelerating after 60. But the Lahav et al. researchers noted that aggressive dieting can speed up this process in younger adults, with metabolic consequences that compound across repeated cycles of weight loss and regain.

When lean mass drops, resting energy expenditure drops with it. That means fewer calories burned at rest each day. It also means less physical capacity — weaker balance, reduced stability, and greater injury risk. The combination makes long-term weight maintenance harder, not easier.

This is why the study’s authors argue that high-quality weight loss should be the standard, not the exception. Losing fat while preserving or increasing muscle isn’t just an aesthetic preference. It’s a protective strategy for long-term metabolic and physical health.

Men and Women: The Same Results Across the Board

One of the clearest takeaways from the study was how consistently results held across biological sex. Men and women both showed the same pattern: resistance training produced superior body composition outcomes compared to aerobic exercise or dieting alone.

In men, the RT group shed an average of 7.7 kg of total weight but lost 8.9 kg of fat — a ratio above 1.0, possible only because lean mass actually increased at the same time. Women in the RT group showed a nearly identical dynamic: 5.42 kg of total weight loss alongside 6.36 kg of fat loss, while fat-free mass increased by 0.9 kg.

Women in the no-exercise and aerobic groups, by contrast, lost 2.94 kg and 0.37 kg of lean mass respectively. Those losses are metabolically significant, especially over time.

Prof. Gepner emphasized in the study’s press release that the benefits were consistent for both sexes. Strength training isn’t a protocol built for one gender and modified for the other. Two to three sessions per week, combined with a moderate caloric deficit and adequate protein, produces meaningfully superior body composition results for men and women alike.

Women have long been steered toward lighter, higher-rep training out of concern about gaining too much size. That concern is largely unfounded at typical training volumes — and this study’s consistent cross-sex results make it even less persuasive. The physiology responds the same way regardless of sex.

Where Cardio Fits: Not the Villain, Just Not the Hero

Aerobic exercise still produced meaningful benefits in this study. The aerobic group lost more fat than the no-exercise group and showed greater reductions in waist circumference. Cardio isn’t the problem — it just isn’t the most effective standalone approach for preserving lean mass during a caloric deficit.

The study didn’t include a combined aerobic-plus-resistance group, so it can’t tell us directly whether stacking both modalities would produce even better outcomes. But the broader research literature consistently suggests that adding cardiovascular work on top of a resistance training foundation improves heart health markers without undermining body composition gains.

The practical takeaway for most people isn’t to drop cardio entirely. It’s to stop treating it as the default and strength training as the optional add-on. The evidence from this study points to resistance training as the foundation, with aerobic work serving as a complement.

The Role of Protein

All participants in this study followed the same protein prescription: 1.5 grams per kilogram of total body weight per day. This level — higher than general population guidelines but well within the range used in body composition research — likely supported muscle retention across all groups.

The advantage seen in the resistance training group came from the training itself, not from a higher protein intake. The groups ate the same way. The difference in body composition outcomes came from what they did physically.

That said, protein intake remains a critical factor for anyone trying to preserve lean mass in a caloric deficit. Without adequate protein, the body can’t repair the microdamage that strength training creates or maintain the muscle protein synthesis needed to hold onto lean tissue. Research on protein timing also shows that synthesis rates stay elevated for roughly three to five hours after a protein-containing meal — which suggests spreading intake across three to four daily meals maintains synthesis more consistently than loading most of it into one or two sittings.

For a 180-pound (82 kg) person, the study’s protein target works out to about 123 grams per day. Good sources include chicken, fish, eggs, Greek yogurt, cottage cheese, legumes, and protein supplements when needed.

A Note on Study Context

The Lahav et al. study stands out for its scale — 304 participants from a real-world clinical nutrition program — and for the precision of DXA body composition measurements over a 5.1-month average follow-up. Longer than many short-term exercise trials, and drawn from real clinical practice rather than a controlled lab environment.

A few limitations deserve acknowledgment. Because participants self-selected their exercise group rather than being randomly assigned, we can’t rule out baseline differences between groups — such as prior training experience, motivation levels, or general activity habits — that may have contributed to the outcomes. Random assignment would eliminate this concern. That said, real-world clinical data like this carries its own value: these are the results people actually achieve when they choose approaches that fit their preferences and lives. The external validity of a self-selected study is, in many ways, higher than a tightly controlled lab trial.

Exercise adherence was also tracked through self-reported logs, which introduces some uncertainty about actual training volume. And the participant pool came from a single nutrition clinic in Israel, which may limit how broadly the findings apply across different populations and healthcare settings.

Still, the direction of the evidence is clear and consistent with decades of controlled research on resistance training and body composition. This study adds a large, real-world clinical data set to a conclusion that exercise scientists have understood for years.

How to Apply This: A Practical Starting Point

The study’s protocol translates well to an everyday setting.

Build Resistance Training Into Your Week

Two to three sessions per week was the frequency used in the study. Each session doesn’t need to be long or complicated. Thirty to forty-five minutes of focused compound movement is enough to generate the signal needed for muscle preservation and lean mass gains.

The study’s resistance training program covered seven upper-body and two lower-body exercises, using weightlifting machines or free weights. Participants started with one to two sets of eight to fifteen reps, progressing to three sets at near-failure. Once they could complete twelve to fifteen reps with control, weight was added and the cycle restarted.

Multi-joint movements are the foundation of this approach: a squat works the quads, glutes, hamstrings, and core simultaneously; a row engages the back, biceps, and core together; a press recruits the chest, shoulders, and triceps at once. These high-efficiency exercises produce more metabolic and muscular stimulus per minute than isolation movements like bicep curls or leg extensions.

For beginners, bodyweight squats, Romanian deadlifts with light dumbbells, push-ups, resistance band rows, and hip hinges are all practical starting points. The weight matters less than the consistency and the effort.

Hit Your Protein Target

The study’s protein prescription was 1.5 grams per kilogram of total body weight per day. Spreading that across three to four meals — rather than concentrating it in one large sitting — supports muscle protein synthesis more evenly throughout the day.

Keep the Caloric Deficit Moderate

All participants followed a roughly 500-calorie daily deficit. The researchers noted that deficits larger than 500 calories per day have been shown to impair muscle protein synthesis — reinforcing the value of a measured, not aggressive, approach to restriction.

Losing roughly 0.5 to 1 pound per week is a pace that tends to spare muscle while making consistent progress on fat. The goal isn’t the fastest possible weight loss. It’s the best possible body composition — and those two things require different strategies.

Conclusion

The Lahav, Yavetz & Gepner study adds clear clinical evidence to an argument that has been building in exercise science for years. When you lose weight, the composition of that loss matters as much as the amount.

Dieting without exercise costs you lean mass. Cardio helps but doesn’t protect muscle the way resistance training does. Strength training was the only approach in this study that produced fat loss while actually increasing fat-free mass — and it did so consistently in both men and women, across a wide range of ages and BMIs, in a real-world clinical setting.

For anyone serious about long-term fat loss and metabolic health, the path is clear: make resistance training the foundation, eat enough protein, and let the caloric deficit do its work without going to extremes.