Balance isn’t just about not falling. It’s about keeping your freedom. It’s about walking on uneven ground without fear. It’s about picking up groceries without second-guessing each step.

Physical therapists draw from decades of research showing which types of exercises prevent falls most effectively. While individual PT programs vary based on patient needs, these three exercises represent the core categories that consistently appear in evidence-based fall prevention programs. They address static balance, dynamic balance, and functional strength—the three pillars identified in major research reviews.

These exercises build on each other. They take 15 minutes, three times per week.

Let’s talk about why three is the right number.

The Science Behind Three Essential Movements

Your body uses three types of balance every day.

Static balance keeps you steady when you’re still. Think about standing at the bus stop or reaching for a shelf.

Dynamic balance keeps you stable while moving. That’s walking down the street or going up stairs.

Functional balance helps during transitions. Getting out of a chair. Stepping over a curb. These moments cause most falls.

Each type needs its own training. You can’t improve dynamic balance by only practicing static holds. Your nervous system needs specific challenges.

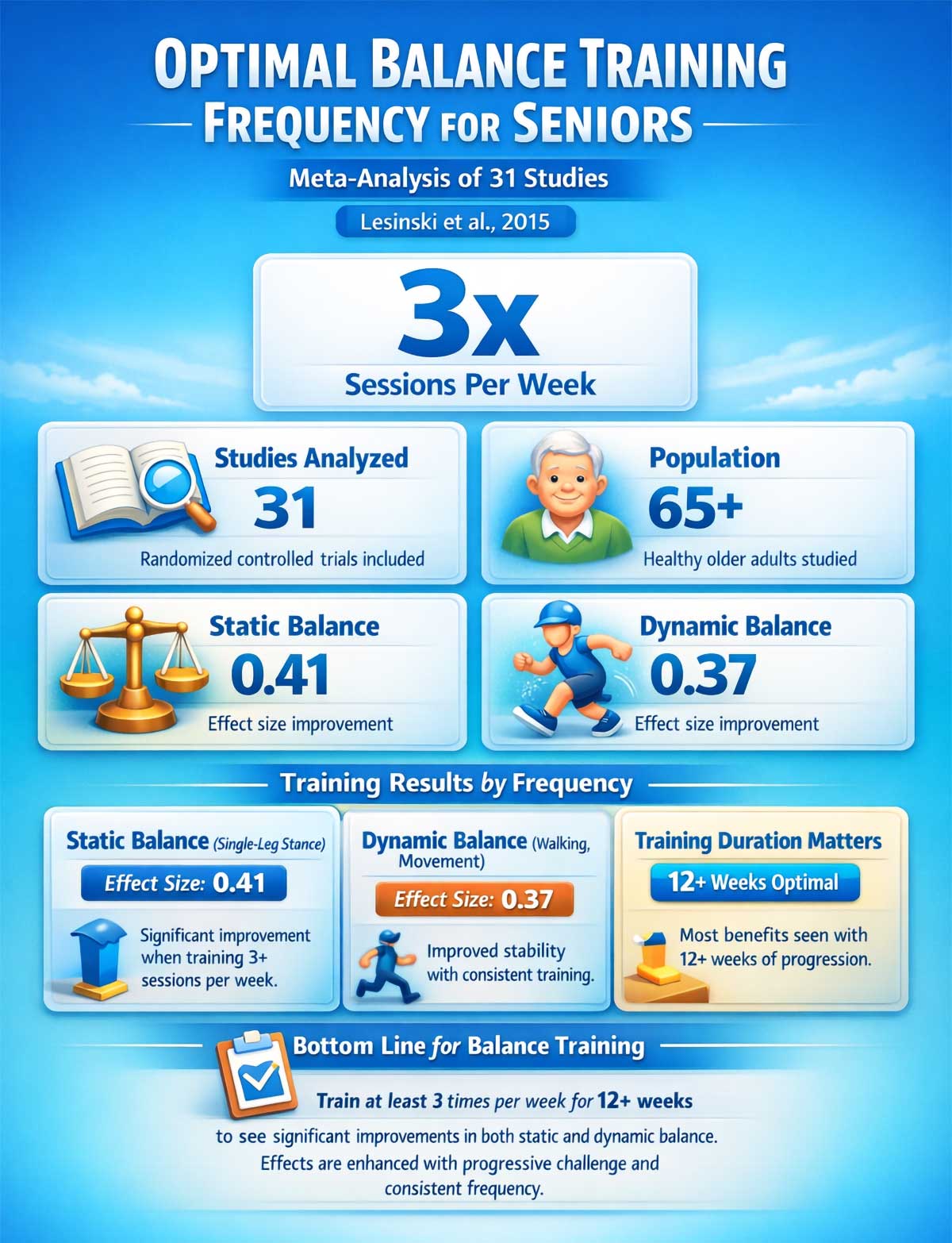

Here’s the thing: your balance system adapts fast. A 2015 analysis of 31 studies involving adults over 65 found significant improvements in both static and dynamic balance when people trained at least three times per week. Your brain builds new pathways. Your muscles respond quicker. Your joints sense position better.

But there’s a catch. The exercise must challenge you. Not scare you. Not make you fall. It needs to push you just past comfort.

Physical therapists call this the “balance challenge principle.” You need to safely stress your center of gravity. Too easy means no progress. Too hard means you’ll quit or get hurt.

A major 2019 review examined 108 studies with 23,407 older adults. The finding was clear: balance exercises that moderately to highly challenge your stability reduced falls by 24%. Three exercises cover all the bases. One for static. One for dynamic. One for functional strength. That’s the formula backed by decades of research.

What the Research Shows

The evidence for these three exercises isn’t just strong. It’s rock solid.

Studies tracking thousands of people show consistent results. Balance training works. But it has to be the right kind of training.

A 2015 meta-analysis by Lesinski and colleagues examined 31 randomized controlled trials. They found that single-leg stance exercises improved static balance with an effect size of 0.41. That’s a meaningful change. The key factor? Training at least three times per week.

The Sherrington team reviewed 108 trials in 2019. This massive analysis included 23,407 older adults. Programs that challenged balance and included functional exercises reduced falls by 24%. The exercises had to moderately or highly challenge the person’s center of gravity.

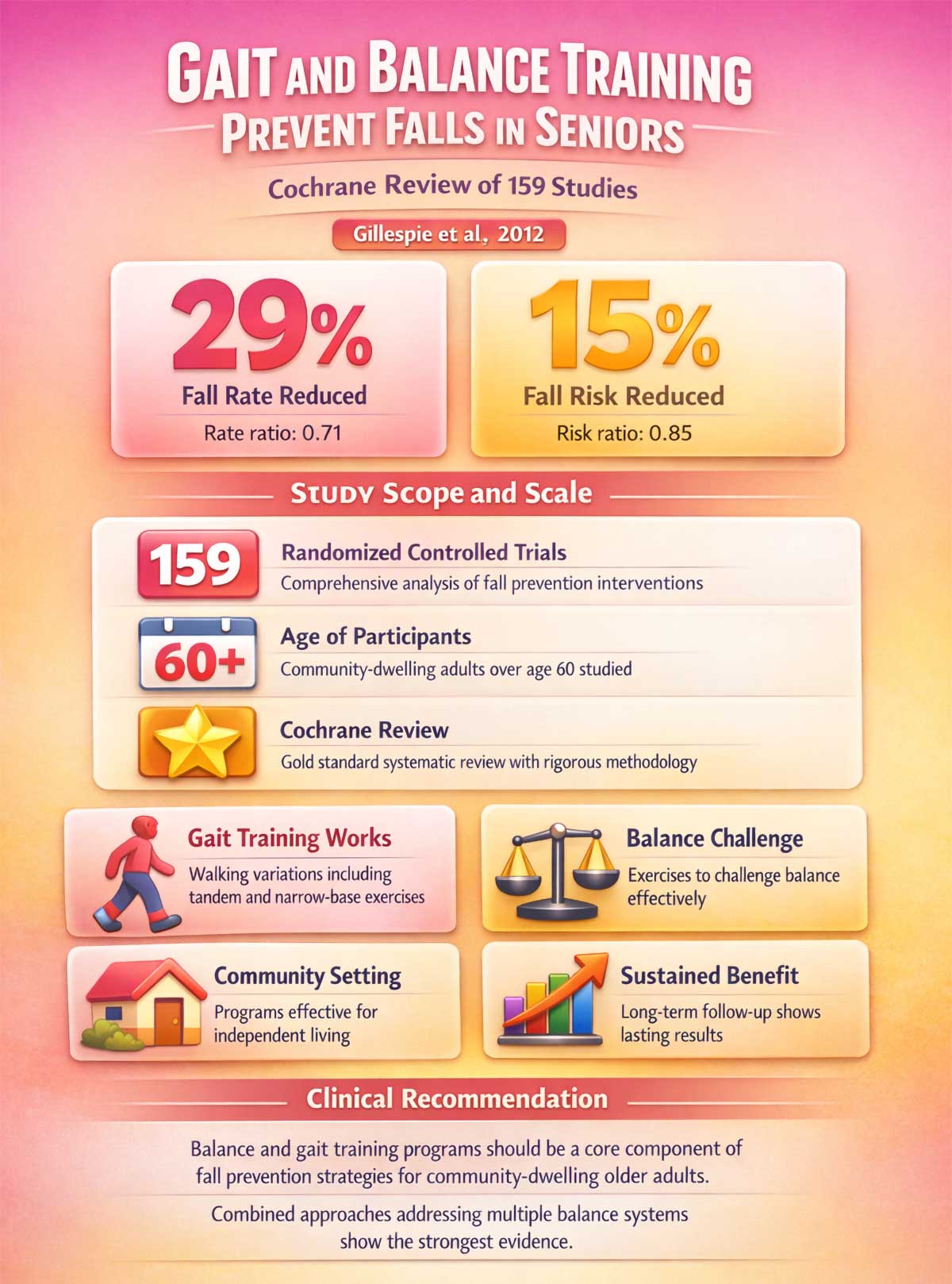

A Cochrane review by Gillespie and team analyzed 159 trials with community-dwelling adults over 60. Balance and gait training programs reduced fall rate by 29%. The risk of falling dropped by 15%.

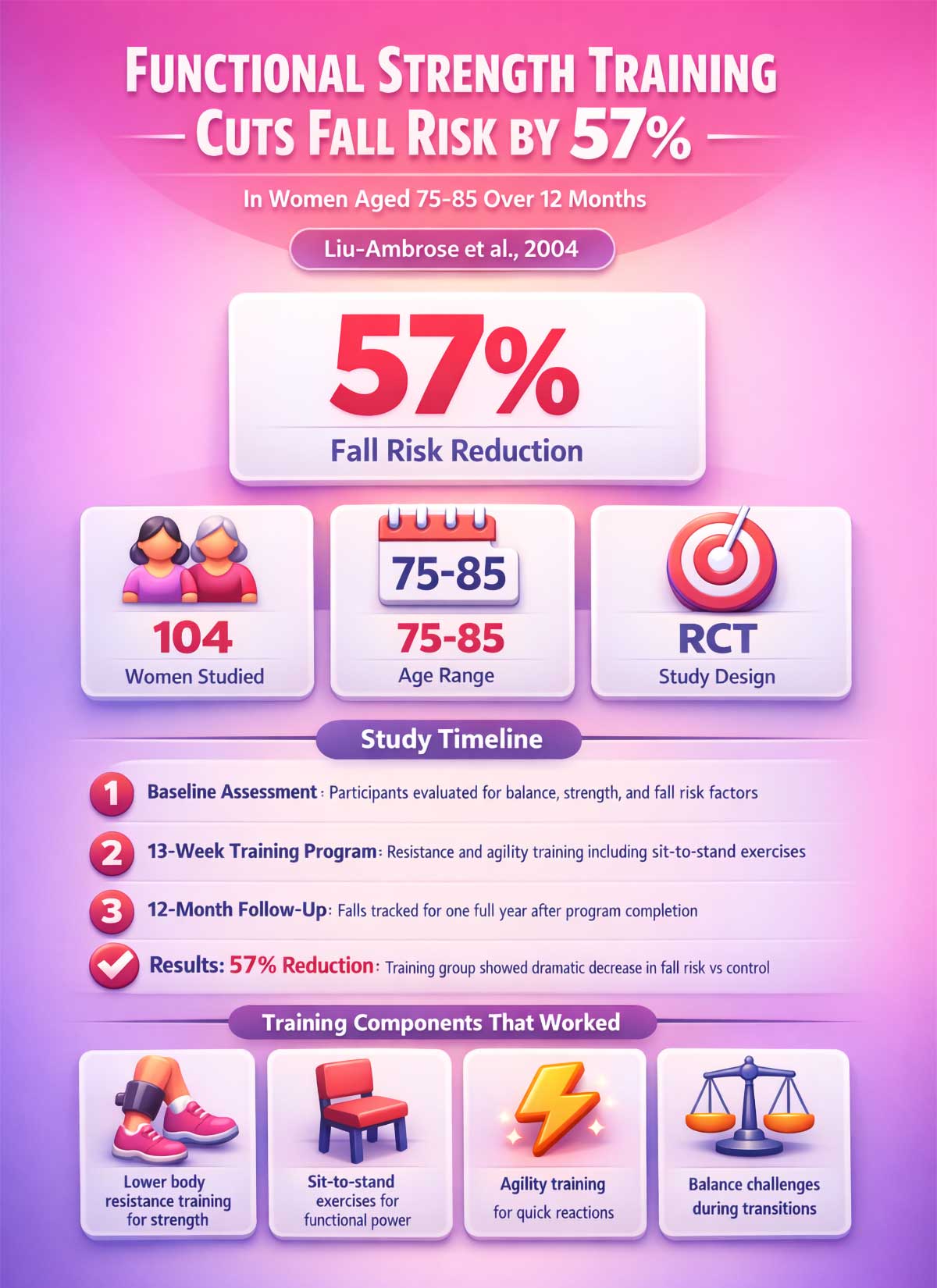

Here’s one of the most striking findings: a 2004 study by Liu-Ambrose followed 104 women aged 75 to 85 through 13 weeks of training. Those who did resistance training including lower body exercises like sit-to-stand variations reduced their fall risk by 57% when tracked for 12 months after the program.

These aren’t small studies. These aren’t weak effects. This is solid science showing that the right exercises make a real difference.

Beyond Fall Prevention: Hidden Benefits of Balance Training

Falls are the obvious concern. But balance training does much more.

Improved posture comes naturally. Balance exercises strengthen core muscles that support your spine. You’ll stand taller without thinking about it.

Better sports performance follows. Golf, tennis, hiking all require strong balance. Your game improves when your base is stable.

Reduced back pain happens for many people. Core activation during balance work stabilizes your lower back. Less strain means less pain.

Increased ankle mobility develops over time. Single-leg work improves ankle range of motion. Stiff ankles loosen up.

Enhanced body awareness grows with practice. You’ll move with more confidence in all activities. You know where your body is in space.

Mental sharpness gets a boost. Balance training requires focus and concentration. This may support cognitive function as you age.

Better reaction time emerges. Your body learns to respond faster to unexpected movements. You catch yourself quicker when something shifts.

Test Your Current Balance in 60 Seconds

Before you start, know where you stand. This quick test takes one minute.

Answer these four questions honestly:

Can you stand on one leg for 10 seconds? Try it now. Lift one foot off the ground. Use light finger support if needed. Can you hold it? Yes or No.

Can you stand up from a chair without using your hands? Sit in a dining chair. Cross your arms over your chest. Stand up. Did you do it without pushing off? Yes or No.

Can you walk heel-to-toe for 10 steps? Put one foot directly in front of the other. Heel touches toes. Take 10 steps. You can use a wall for balance. Did you complete 10 steps? Yes or No.

Have you fallen in the past 12 months? This includes any fall, even if you didn’t get hurt. Yes or No.

Your score:

If you answered Yes to the first three questions and No to the last one, you have good baseline balance. Start with Level 1 of each exercise. You’ll progress quickly.

If you answered Yes to two or three of the first questions, you have moderate fall risk. Start with Level 1. Take your time with progressions. Spend at least two weeks at each level.

If you answered Yes to only one or none of the first questions, you have higher fall risk. Consult a physical therapist before starting these exercises. They can assess your specific needs and modify the program for you.

Who This Program Is Designed For

This balance training program is appropriate for:

- Adults over 50 concerned about maintaining balance and independence

- Those who have noticed minor balance changes but haven’t fallen

- People recovering baseline balance after periods of inactivity

- Anyone wanting to prevent future balance decline

This program may need modification for:

- Those with significant balance impairment or multiple falls

- People with neurological conditions affecting balance

- Anyone recovering from lower body surgery or injury

- Those with severe osteoporosis or joint limitations

A physical therapist can assess your specific needs and modify these exercises appropriately.

Your 4-Week Balance Training Plan

Here’s exactly what to do each week. No guessing. No wondering if you’re doing enough.

Week 1:

- Single-Leg Stance: Level 1, hold 10 seconds, 3 sets each leg

- Sit-to-Stand: Level 1, 8 reps, 2 sets

- Tandem Stance: Level 1, hold 10 seconds each side

- Train 3 times this week (Monday, Wednesday, Friday works well)

Week 2:

- Single-Leg Stance: Level 1, hold 20 seconds, 3 sets each leg

- Sit-to-Stand: Level 1, 10 reps, 2 sets

- Tandem Stance: Level 1, hold 20 seconds each side

- Train 3 times this week

Week 3:

- Single-Leg Stance: Level 1, hold 30 seconds, 3 sets each leg

- Sit-to-Stand: Level 2, 10 reps, 2 sets

- Tandem Walking: Level 2, 10 steps with wall support

- Train 3 times this week

Week 4:

- Single-Leg Stance: Level 2, hold 20 seconds, 3 sets each leg

- Sit-to-Stand: Level 2, 12 reps, 2 sets

- Tandem Walking: Level 2, 15 steps with wall support

- Train 3 times this week

This 4-week plan establishes your foundation. Research shows continued benefits when balance training extends for 12 weeks or longer. After week 4, continue the program for at least 8 more weeks (12 weeks total) before reassessing. The Lesinski meta-analysis found that programs lasting 12 or more weeks with ongoing progression produced the most substantial improvements in balance outcomes.

Exercise 1: The Single-Leg Stance

Stand on one foot right now. Go ahead. Try it for 10 seconds.

How’d that go?

If you wobbled after three seconds, you’re not alone. If you couldn’t lift your foot at all, that’s useful information. This simple test tells physical therapists more about fall risk than almost any other measure.

Why This Exercise Works

Single-leg stance is pure static balance. Your ankle makes tiny adjustments. Your core fires to keep you upright. Your eyes, inner ear, and joints all send signals to your brain.

Research shows people who can’t stand on one leg for at least 20 seconds have a higher fall risk. The good news? You can train this. A 2011 meta-analysis by Howe and colleagues examined 94 trials with older adults. Standing balance exercises including single-leg stance showed improvements in balance outcomes with an effect size of 0.52. That’s a substantial change.

Here’s what happens inside your body: Your ankle muscles make small corrections. These micro-movements aren’t mistakes. They’re your balance system at work. Physical therapists watch for these tiny shifts. They show your nervous system is engaged.

How to Do It

Start near a sturdy chair or counter. You’ll use it for light support.

Stand with feet hip-width apart. Pick one leg to lift. Shift your weight to the other leg. Place just your fingertips on the chair.

Lift your other foot a few inches off the ground. Bend your knee slightly. Don’t lock your standing leg.

Keep your gaze forward. Pick a spot on the wall. Looking down makes it harder.

Hold for 10 seconds. Build up to 30 seconds. Do three sets on each leg.

Breathe normally. Holding your breath throws off balance.

What to Expect in Your First Week

Your first attempt might surprise you. Most people can’t hold 10 seconds right away.

Day one, you might manage five seconds. That’s fine. Do what you can. Rest. Try again.

By the third session, you’ll notice improvement. Seven seconds feels easier. Your ankle doesn’t shake as much.

Week two brings real progress. Ten seconds becomes manageable. You use less finger pressure on the chair.

This quick adaptation happens because your nervous system learns fast. Your brain creates new pathways. Neurons fire in new patterns. This is called neuroplasticity. You’re literally rewiring your balance system.

Your Progression Path

Level 1: Use fingertip support on a chair. Hold 10 seconds. Work up to 30 seconds on each leg. Stay here for at least two weeks or six sessions.

Level 2: No hands. Same timing. Master 30 seconds before moving on. This usually takes two to three weeks.

Level 3: Stand on a foam pad or folded towel. The unstable surface forces your ankle to work harder. This trains what therapists call proprioception. That’s your body’s sense of where it is in space. Start with 10 seconds. Build to 30 seconds over three to four weeks.

Level 4: Close your eyes. This removes visual input. Your inner ear and joints must do all the work. Start with just five seconds. This is hard. Even young athletes struggle with eyes-closed balance. A 2015 study found that removing visual input increased the challenge level significantly. Take your time here.

Don’t rush these levels. Spend at least two weeks at each stage. Some people need a month. That’s fine. Your nervous system needs time to adapt.

When to Progress: Your Decision Guide

Can you complete 3 sets at your current level without breaks?

- No → Stay at this level for another week

- Yes → Continue to next question

Have you done this level for at least 2 weeks (6 sessions)?

- No → Complete at least 6 sessions before moving up

- Yes → Continue to next question

Do you feel confident and stable throughout all 3 sets?

- No → Practice 3 more sessions at this level

- Yes → Move to the next level

This decision tree keeps you safe. It prevents overconfidence. It builds a solid foundation.

The PT Secret

Those ankle wobbles you feel? That’s progress, not failure. New clients often say, “I’m so shaky. This isn’t working.”

Wrong. The shake means your balance system is learning. Therapists want to see those micro-movements. A perfectly still stance means you’re not challenging yourself enough.

Your ankle has small muscles that stabilize your foot. They’re probably weak from years of wearing supportive shoes. These muscles need to wake up. The wobble is them waking up.

Physical therapists look for these micro-adjustments. They’re a sign of active balance control. Your body is problem-solving in real time.

Common Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Mistake: Looking down at your feet.

The fix: Keep your gaze forward on a spot on the wall.

Why it matters: This trains your vestibular system, not just visual balance. Real-world balance happens when you’re looking ahead, not down.

Mistake: Locking the knee on your standing leg.

The fix: Keep a slight bend in your standing leg.

Why it matters: A bent knee allows your ankle to make micro-adjustments. A locked knee prevents this natural stabilizing mechanism.

Mistake: Holding your breath.

The fix: Breathe normally throughout the hold.

Why it matters: Breath-holding creates tension. It reduces oxygen to your muscles. Normal breathing keeps you relaxed and balanced.

Quick Recap

Why: Trains static balance and ankle stability. Reduces fall risk. Diagnostic tool for balance assessment.

How long: Hold 10-30 seconds per set. Three sets each leg. Takes about 5 minutes total.

Progression: Four levels from fingertip support to eyes closed on unstable surface.

PT tip: The ankle wobble is progress. It shows your balance system is actively working.

Exercise 2: The Sit-to-Stand

Most falls happen during transitions. You stand up from the couch. You step off a curb. Your body shifts from one position to another.

The sit-to-stand exercise trains exactly this. It builds the leg strength you need to recover from a stumble. It teaches your body to control movement through space.

Why This Exercise Works

Think about getting out of a chair. You lean forward. You shift your weight over your feet. You push up. Your balance changes every second during this move.

The 2004 Liu-Ambrose study provides powerful evidence. They tracked 104 women aged 75 to 85 through 13 weeks of training. Those who did resistance training including lower body exercises reduced their fall risk by 57% when tracked for 12 months after the program.

This exercise does double duty. It strengthens your quads, glutes, and core. And it challenges your balance during a real-world movement. Physical therapists consistently use exercises that check both boxes.

Here’s what makes it special: the lowering phase. When you sit back down slowly, your muscles work even harder. This builds what’s called eccentric strength. That’s the type of strength that catches you when you trip.

The Muscle Groups at Work

Your quadriceps do the heavy lifting. These big muscles on the front of your thigh power you up from the chair.

Your glutes kick in next. These muscles in your backside extend your hips. They bring you to full standing.

Your core stabilizes everything. Your abs and back muscles keep your torso steady as you rise.

Your calves make small adjustments. They control your ankle position. They keep you from tipping forward.

All these muscles must coordinate. That coordination is balance in action.

How to Do It

Use a standard dining chair. No wheels. No arms if possible. Sit with your feet flat on the floor. Your knees should be at about 90 degrees.

Scoot to the edge of the seat. Lean your torso forward slightly. This shifts your weight over your feet.

Push through your heels. Stand up. Don’t use your hands unless you need to.

Pause at the top. Stand tall. Squeeze your glutes.

Now the important part: lower yourself down slowly. Count to three as you sit. One Mississippi, two Mississippi, three Mississippi. Control the descent. Don’t just drop into the chair.

Do 10 reps. Rest for 30 seconds. Do another set of 10.

Your Progression Path

Level 1: Use the armrests for help. Push off with your hands as needed. Focus on the slow lowering phase. Do 8 to 10 reps. Stay here until you can complete 2 sets of 10 easily.

Level 2: Cross your arms over your chest. This removes hand support. Your legs do all the work. If you can’t complete 10 reps, go back to Level 1 for another week.

Level 3: Hover at the bottom. Lower yourself until you’re an inch above the seat. Hold for three seconds. Then stand back up without sitting. This builds serious strength. Start with just five reps. Work up to 10 over several weeks.

Level 4: Lower the chair height. Use a shorter stool or bench. This increases your range of motion. Your muscles work through a bigger arc. Only try this after you master Level 3. A 2012 Cochrane review found that functional exercises addressing real-world scenarios like varying chair heights were particularly effective at reducing falls.

The PT Secret

The slow lowering phase is where the magic happens. Most people stand up fine. Then they plop down hard.

Therapists want you to take at least three seconds to sit. Count it out. “One Mississippi, two Mississippi, three Mississippi.” That eccentric phase builds the strength that prevents falls.

Your quads burn during the lowering. That burn is good. It means muscle fibers are working. Don’t rush it. Quality beats speed every time.

Eccentric training creates more muscle damage than lifting. That sounds bad. It’s not. The damage triggers muscle growth. Your body repairs and builds stronger fibers.

Common Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Mistake: Dropping into the chair quickly.

The fix: Count to three as you lower. Control the entire descent.

Why it matters: The eccentric lowering phase builds strength that prevents falls. Dropping into the chair wastes this benefit.

Mistake: Leaning too far back while sitting.

The fix: Lean forward slightly before standing. Keep your torso angle consistent.

Why it matters: Leaning forward shifts your weight over your feet properly. Leaning back makes the movement harder and less functional.

Mistake: Pushing up on your toes.

The fix: Keep your weight in your heels. Press through your whole foot.

Why it matters: Heel pressure activates your glutes and hamstrings. Toe pressure shifts work to smaller, weaker muscles.

Quick Recap

Why: Builds functional strength during transitions. Reduces fall risk during real-world movements. Strengthens quads, glutes, and core.

How long: 10 reps per set. Two sets. Takes about 4 minutes total.

Progression: Four levels from armrest support to lower chair height.

PT tip: The slow lowering for 3 seconds builds the eccentric strength that catches you when you stumble.

Exercise 3: Tandem Stance and Walking

Balance in real life happens while you’re moving. You walk through a crowded room. You navigate a narrow hallway. You step around your dog.

Tandem exercises train dynamic balance. They narrow your base of support. This mimics the tight spaces you face daily.

Why This Exercise Works

Normal walking uses a fairly wide stance. Your feet land several inches apart. Tandem stance puts one foot directly in front of the other. Heel touches toe.

This narrow base forces your balance system to work overtime. Your core stabilizes your trunk. Your hips keep you from tipping sideways. Your ankles make constant adjustments.

The 2019 Sherrington review provides strong support. Their analysis of 108 studies showed that balance exercises with a narrowed base of support reduced falls by 24%. The key was moderately challenging the balance system. Tandem stance does exactly that.

Walking heel-to-toe also trains your gait. It improves your walking pattern. Many older adults develop a shuffling step. Tandem walking counters that habit.

A 2011 meta-analysis by Howe found that dynamic balance exercises including gait-based activities showed significant improvements with an effect size of 0.52. Tandem walking combines gait training with balance challenge.

Why Walking Patterns Matter

Your gait pattern affects fall risk. A wide, shuffling gait signals balance problems. It also creates new ones.

When you shuffle, you don’t lift your feet high. You’re more likely to trip on small obstacles. A rug edge. An uneven sidewalk. These become hazards.

Tandem walking retrains your gait. It teaches you to place your feet deliberately. You lift your knees. You control your foot placement. These habits transfer to normal walking.

Physical therapists use gait analysis to assess fall risk. They watch how you walk. Tandem walking is both assessment and treatment.

How to Do It

Start with tandem stance. Stand near a wall for safety.

Place your right foot directly in front of your left. Your right heel should touch your left toes. You’re making a straight line.

Keep your gaze forward. Look at the wall, not your feet. This trains your inner ear to work without visual help.

Hold for 10 seconds. Switch feet. Your left foot now goes in front.

Once you can hold 30 seconds on each side, move to tandem walking.

For tandem walking, imagine a straight line on the floor. Place your right heel directly in front of your left toes. Step forward. Now your left heel goes in front of your right toes.

Take 10 steps forward along the wall. Turn around. Walk back. That’s one set. Do three sets.

Your Progression Path

Level 1: Tandem stance only. Hold the position for 10 seconds on each side. Build to 30 seconds. Use the wall for light finger support if needed. Master this before moving to walking.

Level 2: Tandem walking with wall support. Keep your hand on the wall as you take 10 steps. Focus on smooth, controlled movement. The wall provides security as you learn the pattern.

Level 3: Tandem walking without support. Arms out to the sides for balance. Take 10 to 15 steps. If you lose your balance, reset and try again. This is challenging. Take your time.

Level 4: Add head turns. Walk tandem while turning your head left and right. Look to the left. Look to the right. Keep walking straight. This challenges your vestibular system. That’s your inner ear balance organ. Start with just five steps. The 2015 Lesinski analysis found that exercises challenging multiple sensory systems produced the best results.

The PT Secret

Keep your eyes up. New students always look at their feet. That makes it harder, not easier.

Your vestibular system needs to work without visual input. When you look down, you rely too much on your eyes. Train your inner ear by looking forward.

Physical therapists use head turns to make this harder. When your head moves, your inner ear sends different signals. Your body must adapt in real time. That’s advanced training. But it builds real-world balance like nothing else.

Your vestibular system sits in your inner ear. It detects head movement and position. When you turn your head while walking, it must recalibrate quickly. This skill prevents falls when you look around while moving.

Common Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Mistake: Taking big steps while tandem walking.

The fix: Keep steps small and controlled. Heel should touch toe each step.

Why it matters: Big steps widen your base of support. This reduces the balance challenge. Small steps maintain the narrow base that makes this exercise effective.

Mistake: Looking at your feet.

The fix: Keep eyes forward on the horizon or a spot on the wall.

Why it matters: Looking down trains visual dependence. Looking forward challenges your inner ear balance system and proprioception.

Mistake: Walking too fast.

The fix: Move slowly and deliberately. Quality over speed.

Why it matters: Fast movement relies on momentum, not balance control. Slow movement forces precise muscle activation and balance correction.

Quick Recap

Why: Trains dynamic balance while moving. Improves gait pattern. Challenges balance with narrowed base of support.

How long: Hold 10-30 seconds for stance. Walk 10-15 steps for walking. Three sets. Takes about 6 minutes total.

Progression: Four levels from static stance to walking with head turns.

PT tip: Keep your gaze forward, not at your feet, to train your vestibular system properly.

Your Safe Start Checklist

Important: These exercises are appropriate for generally healthy adults concerned about maintaining or improving balance. If you have significant balance problems, a history of multiple falls, neurological conditions, or are recovering from surgery or injury, consult a physical therapist for a personalized assessment before beginning any balance program. A PT can identify specific deficits and create a tailored program for your needs.

Balance training is safe for most people. But smart setup prevents problems.

Create Your Training Space

Pick a corner of a room. The corner gives you two walls for support. You can’t fall backward. You can catch yourself on either side.

Remove rugs and clutter. You need a clear space about six feet square. No toys, shoes, or cords.

Wear shoes with good grip. Or go barefoot. Socks are slippery. Slippers often lack support.

Good lighting matters. You want to see clearly. But you’ll also practice with eyes closed later. Make sure you can do both safely.

Keep a sturdy chair nearby. You’ll use it for single-leg stance. Make sure it won’t slide. Put it on a rug or against a wall.

What You Need (And What You Don’t)

Essential items:

- Sturdy chair without wheels (dining chair works great)

- Clear floor space measuring 6 feet by 6 feet

- Good lighting from overhead or windows

- Non-slip footwear or bare feet

Optional but helpful items:

- Foam balance pad for Level 3 progressions (costs $15-30 at sporting goods stores)

- Yoga mat for cushioning your knees during setup

- Timer or phone stopwatch to track hold times accurately

- Progress journal or notebook to record your numbers

Free alternatives you already own:

- Folded bath towel instead of foam pad (fold it twice for thickness)

- Cushion from your couch for an unstable surface

- Lower stool or bench from your home for sit-to-stand progression

- Kitchen timer instead of phone stopwatch

Modifications for limited mobility:

- Use your kitchen counter instead of a chair for more stable support

- Start with both hands on support, then progress to one hand

- Use the arm of your couch for sit-to-stand practice (adds height)

- Reduce hold times to 5 seconds and build up slower over weeks

You don’t need a gym. You don’t need expensive equipment. Your home has everything you need.

Know When to Get Help

Some balance problems need medical attention. Watch for these red flags:

Dizziness is different from unsteadiness. Dizziness feels like the room is spinning. Unsteadiness feels like you might tip over. Spinning sensations need a doctor’s exam. Your inner ear might have an issue. This could be benign positional vertigo or something else.

Sudden changes in balance. If your balance got worse quickly, see your doctor. Gradual decline is normal with age. Sudden changes can signal other problems. Stroke, medication side effects, or inner ear infections all cause rapid balance loss.

Numbness in your feet. Balance partly depends on feeling the ground. If your feet are numb, tell your doctor. This could indicate nerve issues. Diabetes and other conditions cause peripheral neuropathy.

Recent falls. If you’ve fallen in the past three months, get assessed. A physical therapist can identify specific weaknesses. They’ll create a targeted program for your needs.

Don’t wait if something feels wrong. These exercises help healthy balance systems. They can’t fix underlying medical issues.

Special Considerations for Common Conditions

Osteoporosis: Safe to do all three exercises. Avoid jerky movements. Use chair support liberally. The bone stress from balance training actually helps maintain bone density.

Arthritis: You may need a higher chair for sit-to-stand. Stack cushions to raise the seat. Warm up your joints before training. Gentle ankle circles and knee bends prepare stiff joints.

Neuropathy: Focus on visual and chair support since foot sensation is reduced. Work with a physical therapist. They can modify exercises for reduced sensation.

Vertigo: Get medical clearance first. Start with eyes open only. Progress very slowly. Some types of vertigo improve with specific exercises. Others need medical treatment first.

Recent surgery: Wait for doctor clearance. Start at Level 1 regardless of previous fitness. Hip, knee, or ankle surgery all affect balance. Rebuild slowly.

Heart conditions: These exercises are low-intensity. But check with your cardiologist first. Balance training is generally safe for stable heart conditions.

Start Slow

Your first session might humble you. That’s normal. Everyone starts somewhere.

Do each exercise for just one set. See how you feel the next day. Some muscle soreness is fine. Joint pain means you pushed too hard.

Build up over two weeks. Add a second set in week two. Add a third set in week three. Your body needs time to adapt.

Three times per week is the research-backed minimum. More isn’t always better for balance training. Your nervous system needs rest days to build new pathways. A 2006 clinical review by Rubenstein found that exercise programs spaced across the week showed better adherence and results than daily training.

What a Sample Week Looks Like

Knowing when to train removes guesswork. Here’s a proven schedule.

Monday: Full routine (15 minutes)

- Warm up: March in place for 30 seconds, gentle ankle circles

- Single-leg stance: 3 sets each leg at your current level

- Rest: 30 seconds

- Sit-to-stand: 2 sets of 10 at your current level

- Rest: 30 seconds

- Tandem stance or walking: 3 sets at your current level

- Cool down: Gentle ankle circles, calf stretches

Tuesday: Rest day Your nervous system needs time to adapt. Rest is when the learning happens. Your brain consolidates the new movement patterns.

Wednesday: Full routine (15 minutes) Same structure as Monday. Try to match or slightly improve your Monday performance.

Thursday: Rest day Active rest is fine. Take a walk. Do some gardening. Just avoid formal balance training.

Friday: Full routine (15 minutes) Your best session often happens on Friday. You’ve trained twice this week. Your body remembers the patterns.

Saturday and Sunday: Rest or light activity Walking, stretching, or gentle yoga all complement balance training. Avoid intense leg workouts that might interfere with your Monday session.

This schedule gives you 48 hours between sessions. That’s the sweet spot for nervous system adaptation.

Track Your Progress

Numbers motivate. Watching improvement keeps you going.

Use this simple tracking chart. Test yourself once per week. Pick the same day each week. Friday works well because it’s your third training day.

Your Progress Tracking Chart:

| Date | Single-Leg Right (sec) | Single-Leg Left (sec) | Sit-to-Stand (reps no hands) | Tandem Walk (steps no support) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | ___ | ___ | ___ | ___ | |

| Week 2 | ___ | ___ | ___ | ___ | |

| Week 4 | ___ | ___ | ___ | ___ | |

| Week 8 | ___ | ___ | ___ | ___ | |

| Week 12 | ___ | ___ | ___ | ___ |

Instructions: Test yourself once per week on Friday. Record your best performance for each exercise. Don’t max out. Stop when form breaks down. Watch the numbers climb over weeks.

In the notes column, write how you felt. “Ankle felt stronger.” “Less wobble today.” “Needed wall less.” These observations matter. They show progress beyond numbers.

What to Expect Month by Month

Month 1: Improved awareness of your balance system. Increased confidence with support. Hold times extend 5-10 seconds. You’ll notice the exercises feel more familiar. Your body remembers the positions.

Month 2: Noticeable steadiness during daily activities. Less reliance on support. Beginning to challenge yourself with Level 2-3 progressions. Walking feels more controlled. You catch yourself faster when you stumble.

Month 3: Significant improvement in balance tests. Reduced wobble. Comfortable with more advanced progressions. This aligns with research showing sustained programs of 12 or more weeks produce the most substantial benefits. Your confidence in daily activities increases. You move with less hesitation.

Balance Training and Related Health Topics

Balance doesn’t exist in isolation. It connects to other aspects of health.

Balance and bone health work together. Strong balance reduces falls. But bone density matters too. Weight-bearing exercises help both. Walking, hiking, and these balance exercises all stress your bones. That stress signals your body to maintain bone strength.

Balance after injury needs attention. Ankle sprains and knee injuries impair balance. The injured joint loses proprioception. These exercises help rehabilitation. They retrain the nervous system. Start slow after any injury. Get clearance from your doctor or physical therapist first.

Balance and medication sometimes clash. Some medications cause dizziness. Blood pressure meds can make you lightheaded when standing. Sedatives affect coordination. Talk to your doctor if you take these medications. They might adjust dosing or timing.

Balance and vision are partners. Vision changes affect balance. Your eyes provide crucial input to your balance system. Get annual eye exams to catch issues early. Update your glasses prescription. Good vision supports good balance.

Balance and footwear connect directly. Proper shoes support balance training. Avoid thick, cushioned soles that reduce ground feel. Your feet need sensory input. Thin, flexible soles work best. Or train barefoot indoors. Many physical therapists prefer barefoot training for this reason.

Consistency Wins Over Intensity

You don’t need to train like an athlete. You need to show up three times per week.

Studies show clear results in four to six weeks. Your balance scores improve. Your confidence grows. The wobbles decrease. The 2015 Lesinski meta-analysis found that programs lasting at least four weeks with three sessions per week produced the best outcomes.

But here’s the truth: you have to keep going. Balance is like fitness. You lose it if you stop training.

Think of this as a 15-minute habit. Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday. Same time. Same spot. Your body learns to expect it.

Set up your space once. Keep it ready. The chair stays in the corner. The foam pad sits nearby. When training is easy to start, you’ll actually do it.

Track your progress simply. How long can you hold single-leg stance? How many sit-to-stands without hands? Can you take 10 tandem steps without touching the wall?

Write these numbers down. Check them monthly. You’ll see improvement. That progress fuels motivation.

The payoff shows up in daily life. You step over the dog with confidence. You reach for the top shelf without fear. You walk on uneven sidewalks without watching every step.

That’s freedom. That’s independence. That’s why physical therapists rely on these three foundational exercises. They represent the core balance categories proven effective in decades of research.

Start today. Pick your corner. Set up your chair. Try one set of each exercise.

Your balance system is waiting to improve. Give it the challenge it needs.

References and Research

This content was developed using evidence-based research from peer-reviewed studies. The recommendations align with physical therapy guidelines for fall prevention and balance training.

Key studies referenced:

Lesinski M, Hortobágyi T, Muehlbauer T, Gollhofer A, Granacher U. Effects of balance training on balance performance in healthy older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2015;45(12):1721-1738.

- Meta-analysis of 31 randomized controlled trials examining balance training in adults 65 and older

- Found significant improvements in static balance (effect size 0.41) and dynamic balance (effect size 0.37)

- Identified three or more sessions per week as optimal training frequency

Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, et al. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1(1):CD012424.

- Comprehensive meta-analysis of 108 randomized controlled trials including 23,407 older adults

- Demonstrated that balance exercises moderately to highly challenging stability reduced falls by 24%

- Programs with functional exercises showed superior outcomes

Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD007146.

- Cochrane review analyzing 159 randomized controlled trials

- Community-dwelling adults over 60 showed 29% reduction in fall rate

- Risk of falling dropped by 15% with balance and gait training programs

Liu-Ambrose T, Khan KM, Eng JJ, Janssen PA, Lord SR, McKay HA. Resistance and agility training reduce fall risk in women aged 75 to 85 with low bone mass: a 6-month randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):657-665.

- Randomized controlled trial of 104 women aged 75 to 85

- 13-week training program including resistance and functional exercises

- Fall risk reduced by 57% at 12-month follow-up

Howe TE, Rochester L, Neil F, Skelton DA, Ballinger C. Exercise for improving balance in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(11):CD004963.

- Meta-analysis of 94 randomized controlled trials in older adults with mean age 69 to 86

- Standing and dynamic balance exercises showed significant improvements

- Effect size of 0.52 for balance outcomes

Rubenstein LZ. Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing. 2006;35 Suppl 2:ii37-ii41.

- Clinical review of multifactorial fall prevention interventions

- Found that functional exercise training addressing real-world scenarios was a core component

- Exercise programs spaced across the week showed better adherence than daily training

American Physical Therapy Association. Physical Therapist’s Guide to Falls. Patient education resource. Updated 2024.

- Evidence-based patient education outlining balance and functional training for fall prevention

- Emphasizes progressive challenge and individualized assessment

- Available at: https://www.choosept.com

These studies represent thousands of participants tracked over months and years. The evidence is strong. The exercises work.

FAQs

What if I can’t lift my foot at all for single-leg stance?

Start with a weight shift. Keep both feet on the ground. Shift 80% of your weight to one leg. Hold for 10 seconds. Feel the pressure in that leg. This builds the first step. Do this for one week. Then try lifting your foot an inch off the ground.

How do I know if I’m progressing too fast?

You should complete 3 sets comfortably at your current level for at least 5 sessions before moving up. If you can’t finish all sets, stay at that level another week. If you feel unstable or scared, drop back one level. Fear means you’re not ready.

My knees hurt during sit-to-stand. What should I do?

Use a higher chair. Stack cushions on your current chair to raise the height. This reduces knee bend and strain. Work with that height until strength improves. You can also try a wider stance. Place your feet slightly wider than hip-width. This changes the angle at your knees.

I feel dizzy when I close my eyes. Is that normal?

Some unsteadiness is normal when removing visual input. But if the room spins or you feel nauseous, stop. Keep eyes open for now. See your doctor about the dizziness. True spinning vertigo needs medical evaluation. It might be benign positional vertigo, which has specific treatments.

Can I do these exercises every day?

Three times per week is optimal. Your nervous system needs rest days to adapt. More frequent training doesn’t speed up results. It can cause fatigue. Studies show the best outcomes with three sessions per week spread across seven days.

How long until I see results?

Most people notice improvement in 3 to 4 weeks. You’ll feel more stable. Your hold times will increase. You’ll use less support. Visible changes take consistency over months. Balance is like strength. It builds gradually with regular practice.

What if I miss a week of training?

You’ll lose some progress, but not all of it. Your nervous system retains learning for several weeks. Jump back in at a slightly easier level. You’ll catch up quickly. One missed week won’t erase all your work.

Should I do these exercises if I’ve never fallen?

Yes. Prevention is easier than recovery. These exercises maintain the balance you have. They prevent future decline. Think of it like brushing your teeth. You don’t wait for cavities to start.